‘Herbert Booth and Joseph Perry’s Soldiers of the Cross of 1900’, National Film and Sound Archive, Arc Cinema, 1 March, 2013

I’d like to thank Quentin for the opportunity, and Clare, Darren and Brooke for the yummy files.

I want to go back to the turn of last century and try to re-imagine the experience that audience members might have had at the Salvation Army evangelist lecture Soldiers of the Cross. This massive production, the most elaborate of the Army’s many technologically cutting-edge productions, was seen by large numbers of people around Australia, and was particularly aimed at recruiting young men.

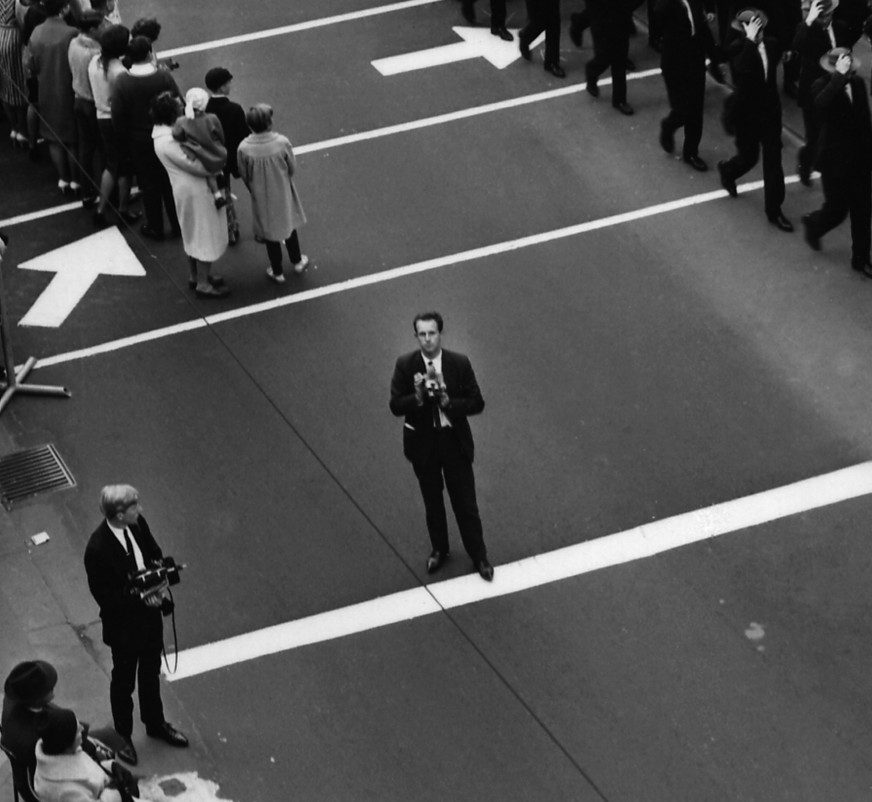

What other media experiences would the excited crowds we see milling about Her Majesty’s Theatre in Melbourne or the Sydney Town hall have had, before the went inside to take their seats? They would certainly have seen many dissolving view magic lantern shows, featuring hand painted slides in series such as Jane Conquest, or life model slides of actors in tableau vivant photographed against backdrops, such as Daddy. These slide shows used a dissolving mechanism to produce special effects by, for instance, dissolving an angel over a scene with a separate magic lantern, or creating a montage on the slide itself. They would have experienced stereo views, where they clamped a viewer onto their face and immersed themselves in virtual three dimensional space as they took a trip through a sequence of twelve scenes, usually of exotic locations they had no hope of visiting in real life. They might have visited one of the new kinetoscope parlours — there was one across the road from the Army headquarters — where they could bend their heads to eyepieces and crank through sixty seconds of animated pictures. They may even have seen animated pictures projected onto a screen from an adaptor placed at the front of a magic lantern. They might have gone to the Melbourne cyclorama building, where they could immerse themselves bodily in a panorama of the Siege of Paris. And they would have been aware of the great celebrity paintings of the day which they would have mainly know from numerous lantern slide reproductions or prints, but even perhaps by experiencing the aura of the paintings themselves. Some celebrity paintings such as Holman Hunt’s 1850s Light of the World, after being familiar for decades through slide and reproduction, physically toured the world like aging rock stars. And finally they would have experienced the hurly burly of the cosmopolitan streets themselves.

All this can be summed up in three buzz words from the period: thrills, animated photographs and colour. So all that was in their heads as they took their seats, but what had been going on behind the scenes? Soldiers of the Cross was produced in the Salvation Army’s Limelight Studios, headed by Joseph Perry, which combined gramophones, magic lanterns and the kinematograph in a ‘triple alliance’. However the key piece of equipment was the most unglamorous, and the most overlooked — it was the copy camera, which could take virtually any flat image, and turn it into a glass slide that could them be hand-coloured before projection. For this production Perry, along with the Commandant of the Army in Australia Herbert Booth and his wife Cornelie produced about 250 glass lantern-slides and approximately fifteen sixty-second strips of Lumiere film. Of the slides about thirty were copied from other sources, and of the films about two were produced by the Lumiere company. The rest were produced in Melbourne, and the whole lot was integrated together by the Booths and Perry. The script has been lost, as well as the films the Army shot. But a large proportion of the slides, and two Lumiere films, survive.

The best way of thinking about the logic of Soldiers of the Cross is to imagine it as a turn of the twentieth century Powerpoint. Like Powerpoint it brought together disparate sources into a singly formatted lecture. Like Powerpoint every time it was performed it was slightly different. And like Powerpoint it was the lecturer who made the show. The Booths wrote the script and read it, while Perry and his team dissolved the slides one into the other and projected the cinematographs. A band also played well-known hymns from the period, and led the congregation is singing. Although it included narratives, these were chapters embedded in an overarching structure which was liturgical and sermonic.

THE ST STEPHEN SEQUENCE

The production began with general scenes of the Life of Christ derived from reproductions of prints and painting, as well as two commercial kinematographs which were each one-minute reels, Christ’s Entry into Jerusalem and the Crucifixion, from the thirteen one-minute-reels of the Lumiere production The Life and Passion of Jesus Christ made in 1898. It is important to look carefully at these Lumiere films. Although they weren’t shot in Melbourne they give an indication of what the Melbourne footage may have looked like. In these films it is the micro-movements, the swish of the palm fronds, the pounding of the Roman hammer, and the movement of the sponge through the air, these unmistakable markers of living animation, which would have most excited the audience.

After this introduction the first chapter of the lecture was the Martyrdom of St Stephen. This is based on the biblical story of the first Martyr. It opens with St Stephen before the Jewish court. Why, one wonders, does this first chapter open with five very repetitive slides where not much is happening, where the narrative isn’t moving? This is because in Chapter 7 of the Acts of the Apostles St Stephen spends 53 Biblical verses defending himself against the Jewish court by recounting the story of Moses’ persecution. So it appears as though these slides would be dissolved, one in to another, perhaps quite slowly, as Booth recounted those 53 biblical verses.

After that, the Biblical narrative suddenly picks up. Stephen looks up and Heaven opens up to him. There he sees God with Jesus on his right hand. The Bible says:

But he, being full of the Holy Ghost, looked up steadfastly into heaven, and saw the glory of God, and Jesus standing on the right hand of God, and said, Behold, I see the heavens opened, and the Son of man standing on the right hand of God. Then they cried out with a loud voice, and stopped their ears, and ran upon him with one accord, and cast him out of the city, and stoned him: and the witnesses laid down their clothes at a young man’s feet, whose name was Saul. And they stoned Stephen, calling upon God, and saying, Lord Jesus, receive my spirit. And he kneeled down, and cried out in a loud voice, Lord, lay not this sin to their charge. And when he had said this, he fell asleep.’ Acts 7 55-60

Booth and Perry have superimposed a commercial slide of Jesus and angels for the effect of Heaven opening up.

The way the slides in this sequence have been made differ. We begin with slides shot with live models standing in front of a painted backdrop. But the slide of St Stephen being removed from the city is assembled in a different way. It is a collage of cut-out photographs pasted onto a painted background, and re-shot onto a glass-slide before being hand-coloured. Both quite different techniques are used throughout the Army’s productions.

The slides only follow the Biblical text loosely, but the general narrative would have been familiar enough to the audience. The account of this chapter in the Salvation Army magazine the War Cry closely follows the slides we have:

The events that lead to the martyrdom of Stephen passed in review. The [Sanhedrim, the] trial, Stephen’s impeachment by the rulers and the stoning of the first martyr. The kinematograph was employed in this latter scene. The effect on the audience, as they beheld in a moving picture the innocent Stephen cruelly beaten to the earth, and killed by fiendish fanaticism of the formal religionists of his day cannot be described. The kinematograph give place to a picture of Stephen lying dead upon the roadside, while Paul (sic) the persecutor stands over him in an attitude of painful contemplation.’ (MWC 22/9/00 p9)

The backdrop painting for the exteriors has clearly been inspired by a Gustave Doré engraving. There are three slides numbered in sequence for the stoning, two are shot against a backdrop, the third is a collage. The kinematograph would have come after this sequence of slides, which may have been dissolved more quickly, perhaps, than the earlier court slides. So the audience would have seen the same action again, repeated, but this time in moving picture.

We can get an indication perhaps of how this might have worked by looking at the script of a later set of life model slides called Lazarus, produced by the Army in 1902. This is a set of eight slides. The script for the later and shorter slide set tells the story of the raising of Lazurus with the usual cues for slide changes. At the end of the story the cue changes to ‘Kino’. Unfortunately the corner of the script has been torn off, but the lecturer says something like:

We shall now show you … (missing) … actually took place … (missing) … this remarkable miracle, most impressive and realistic. WE WILL SHOW YOU IN LIVING FORM WHERE MARTHA MEETS CHRIST, and tells him Lazurus is dead,…….’

The script then runs on as a commentary on the kinematograph, with prompts for the reader of the script for when the kinematograph scenes will change.

To return to the earlier, longer, Soldiers of the Cross production, as the War Cry says, the kinematograph then gives way to a slide of Stephen lying dead, with Jesus receiving his spirit. Then we see a hand-coloured copy of a lithographic reproduction of a Pre-Raphaelite Millais painting of St Stephen, before cutting back to two slides of Salvation Army Officer Colonel James Annetts, who played St Stephen, lying on the ground. Between the final two slides we see his crimson blood poo, as though a few moments of time have elapsed, and a crucial character for the next chapter, Saul, appear to look over him.

So in this chapter, even though viewers are experiencing a synthesized production, it is not built on anything like a unified visual syntax. Instead they are experiencing at least five different modalities of affect, and four different expressions of time:

- A strophic, verse-like, iterative mode of slowly dissolving lantern slides, familiar from previous commercial slide sets

- An expository mode of tableaus taking us through key narrative points

- A faster, time-based, action mode, often in couplets or triplets, and perhaps linked to an accelerated lantern dissolve, which is an innovation of the commercial slide format

- The real-time animation and realistic living-picture mode of the kinematograph, giving a visceral feeling of natural movement

- The contemplative mode of a familiar work of ‘great art’ which is embedded in some kind of universal historical/symbolic/aesthetic time

These five different modalities I have identified are reflected in the contemporaneous comments on the production. For instance often the micro-movements magically captured by the kinematograph are mentioned, such as the splash of water as a martyr is thrown in a river, the rising of smoke, or the falling of stones. But also the beautiful colour of the slides is frequently mentioned. All of these modes, although not syntactically unified in any way we would recognize from subsequent cinema history, nonetheless worked together to directly involve the audience with the story through shared sight. This sense of collective witnessing, which this opening sequence sets up, is caught well by the War Cry:

We saw the great stones falling thick and fast upon the white robbed figure on the ground, till it grew strangely still. Then the ‘witnesses’ left the scene, and Saul of Tarsus stood alone looking down upon the dead young man. (MWC 29/9/00 p14)

SAUL

The next slide, after we have shared with Saul our contemplation of the dead St Stephen, is a shot of contemporary Damascus extracted from a stereograph. But this clever segue still follows the Bible pretty closely, because after being transported to contemporary Damascus as it was in 1900, the next slide whooshes us back to Biblical times for Saul’s conversion. We then see a tight sequence of three slides, shot outside rather than in a studio, which is a time-based triplet shows us St Paul’s escape by basket from the walls of Damascus to continue his preaching.

These time-based ‘runs’ of slides often seem to pick up momentum towards a kinematographic climax. For instance at slide number 72 there is a sequence of Romans raiding an outdoor service by Christians who are then forced to flee underground to continue their worship clandestinely in the catacombs. In 1901 this sequence was added to with a kinematograph of the Romans chasing the Christians across a plank over a stream, augmented with the much commented on comic relief of a Roman boinging off the springy plank and into the stream.

CATACOMBS

A later sequence focuses on life in the catacombs, perhaps to parallel life for Salvationists in the midst of pagan Melbourne. Like an establishing shot from a movie of twenty years later, it begins with an aerial map of the catacombs, and then swoops us down through the contemporary underground stone passages using stereo views from a commercial stereograph set. We then see daily life— worship, marriage, birth, sickness and eventual death — carried on in what I have called the ‘iterative’ mode through a mixture of Army collages and copies of prints and engravings. As the War Cry put it:

All these scenes, painted and reproduced to sight and sound by word and art pictures, simply enchain the mind, and carry one in thought 1800 years back through the ages. The listener sups, prays, praises, adores worships, suffers and dies with these saints of apostolic times.

The mode switches from ‘iterative’ to ‘time-based’ for a detailed and strangely beautiful, even today, funeral sequence of four monochrome slides. Once more there is kinematographic climax, before a final extended contemplation of souls ascending into heaven painted in brilliant supersaturated colour, which may perhaps have been accompanied by music or singing.

LIME KILNS

About twenty slides later another quartet of slides appears which encapsulates a tight action. A Christian woman is about to be burnt to death in a lime-kiln. Will she offer just one grain of incense to the Pagan Gods and save herself? No! After pointing upwards to the one true God she disappears into the kiln. This again was followed by a kinematograph of martyrs joyfully jumping into the kiln, with the added bonus of smoke effects.

COLISUEM

Fourteen slides later another run of five slides introduces an extended piece of action. Christians wait at the gate of the Coliseum, while a stuffed tiger with a virulent red tongue threatens them from a cage. Then the gates inch open in the final three slides, before a kinematograph shows the Christians entering the Coliseum and being approached by lions, after which individual slides show their martyrdom.

PERPETUA SEQUENCE:

The final sequence of the two and half hour show was for many people the most affecting, in Hobart for instance, it caused ‘general sobbing’ in the audience. (MWC 26/1/01 p9)

Perpetua, played by the young, attractive Army member, Cadet Mabel Tolley was a young wealthy Roman woman who chose to give up her baby and be martyred in the coliseum rather than renounce Christ. A script with slide and music cues exists, probably for a stand-alone version made shortly after Soldiers of the Cross. The surviving script is also punctuated with nine popular hymns requiring audience participation, with a hymn supplementing the narrative about every four slides. However in Soldier of the Cross itself there were most probably far fewer hymns because of the whole production’s larger scale.

The script is ekphrastic, that is, it describes what the audience is seeing with their own eyes, and rhetorically explains what they should be feeling. For instance, during a dissolve between two opening slides the script says:

We may picture the surprise of this Christian lady when sitting in one of her well furnished rooms. The stillness of the occasion was broken by the intrusion of two armed men. On learning the object of their sudden appearance, Perpetua showed neither fear nor alarm.

This was immediately followed by a hymn. Later, when she is cast into prison, the script tells the audience:

Glory filled her soul amidst the gloom of her surroundings.

Later on, a tight sequences of slides showed the visual evidence of interpersonal conflict, while the script provided the ekphrasis. After her father leaves, disappointed that he has not been able to convince her to drop the whole Jesus thing, the script says:

This was to her a dark and trying moment. The grey beard, the fatherly face, the agitated frame, the loving entreaties, and the stern rebuke; as well as the somber environment of the place, all spoke to her heart with a weird-like eloquence. Still she faltered not. An invisible power supported her even now.

As we have seen in the St Stephen sequence at the beginning of the production, the script is often self-referential, making direct links between Perpetua’s experience and the experience of the audience seeing the projected slides in Melbourne eighteen hundred years later. After Perpetua has finally handed over her baby to her mother the script says:

But when the mother had gone a dreary lull set in. The baby’s prattle had given way to a deep silence. The past rose in vivid pictures, and strong as she was in the grace of God, her poor heart was grief stricken. But there is always solace in prayer, and even in this dark dungeon Perpetua might well prove the unfailing words, ‘My grace is sufficient for thee’.’

The script then calls for the hymn What a friend we have in Jesus.

In a second courtroom sequence more tight time-based, rather than expository, action is shown. She is offered pagan incense to burn and her mother and father show her the baby which will be returned to her if only she renounce Jesus. She refuses. Her father remonstrates with her once more, and is struck to the round by a guard.

After Perpetua has been martyred and before the final hymn the script ends with:

But the end was near, for soon Perpetua lay bruised and bleeding upon the floor of that slaughter house on iniquity still praying to Him she loved. The excited crowd yelled that her misery and pain might end with a thrust of the gladiator’s sword. A moment later the soul of Perpetua had gone to be with God, gone to hear her master say, “Now that thou hast been faithful unto death, I will give thee a Crown of Life”.

THE VOICE

Now we have looked in as much detail as possible at a few of the many sequences in this production, what general conclusions can be drawn? The unifying force in the piece was the voice, the live human voice reciting that sermon. That voice was provided first by the charismatic Herbert Booth, youngest son of William Booth, the founder of the Salvation Army movement. Herbert spoke in ‘short and harmonious’ sentences, ‘constructed with due regard to the balance and equilibrium of the whole’ (MWC 22/9/00). After he got sick the lecture was conducted by his equally charismatic wife. The War Cry reported:

The lights went down, and the audience were hushed into breathless silence as the immense pictures were thrown upon the canvas. The Commandant’s voice alone broke the stillness thrilling the enthralled audience with burning words fitted in compact sentences, forming an eloquent and beautiful tribute to the heroic deeds and unflinching endurance of the saints whose pictorial reproduction riveted every eye. (MWC 22/9/00 p9)

Other connecting forces were musical, the familiar hymns and masses played by the orchestra and sung by the audience. But the dominant force which distinguished the limelight lecture from others was the lanternist himself, who was always present in the audience’s consciousness as his lanterns hissed and spluttered and projected their beam above their heads. As the War Cry noted:

Carefully watching the screen as the lecture progressed, and noting the rapid changes from one slide to another, from slide to kinematograph film, and then again from kinematograph film to slide, each appearing exactly at the right time, one could not help but admire the consummate skill with which Major Perry manipulated his elaborate and complicated apparatus. (MWV13/10/00 p8)

RETINAL POWER

The presence of the lanternist signaled the radical shift in focus of the site of principle address which the Salvation Army made in their evangelism: from the body, or the ear, or the mind, or the voice — although these were of course still present — to the eye and to the retina; from the phenomenological architecture of the church to the dominating address of the projection sheet; from the magical ritual of the service to the narrative power of the projected image.

The magic lantern shifted the locus of the spiritual to the limelight itself, and turned the lanternist into a kind of thaumaturge. For instance, before the third presentation of Soldiers of the Cross at South Melbourne Town Hall Brigadier Unsworth prayed with the congregation:

that the pictures might be luminous with Divine light, [instilled] with divine power, and fruitful in bringing about more of that spirit of heroism that dominated the lives of the Christian martyrs of old. (MWC 13/10/00 p8)

The Army’s spiritual bellicosity was evoked in another comment by the War Cry:

The lecture is a double-barreled weapon, which captivates both sense of sight and enchains the mind, while indelible impressions are made upon it. (MWC 22/9/00 )

THE DISSOLVE

The Army’s slides, like all slides of the period, were propelled forward by the retinal frisson of the dissolve, as one image appeared to materialize itself within the very optical substance of the image it was replacing. The rhetoric of the Army frequently equates the light of the lantern with the light of salvation, and the magical transformation of the dissolve with the transformative power of Jesus.

INNOVATION

The Army’s main innovation was to use lantern slides to describe tight time-based actions, rather than expository narrative elements or iterative strophic elements. This I think is globally significant at the time.

The Army’s second innovation was to scale up the traditional lantern lecture into a complete evening’s production, and to give it a thematic unity. As the War Cry reported:

Although the audience was taken through a great variety of scene and incident, the intervals were cleverly bridged or, to change the metaphor, the stories, instead of being scattered gems were strung on an elocutionary necklace and, in their semblance or contrast made into a beautiful and complete circlet. (MWC 29/09/00 p8)

A third innovation was to work the kinematograph into the slides more closely. In Booth’s words:

I saw at a glance that living pictures, worked in conjunction with life-model slides, would provide a combination unfailing in its power of connecting narrative.’ (Citation)

THRILLS

These three innovations were all in search of thrills — Army thrills to compete with all of the other thrills young people, particularly young men, had to divert them in 1900. In its pre-publicity for Soldiers of the Cross, the War Cry described it as a ‘new sensation’. It was the power of the thrill which led Booth to chose as his subject the martyrdom of the early Christians, because the bloody and violent martyrdoms provided opportunity for spectacle and action. If the thrill was one key concept, the other was realistic action. The intention was to create a retinal connection between the audience and the Christian martyrs. The ultimate objective was for people, particularly men, to pledge their souls to Christ and their lives to the Army at the end of the lecture. Realism was one conduit of empathy, the other was the contemporary travel shots of the Holy Land and the copies of the great and familiar paintings which introduced each chapter.

As the War Cry predicted before opening night:

The thrilling scenes in the arena, the cruel tests, the thrilling presentiments of Christians under torture, the sustaining power of the presence of the invisible Christ should bring forth all that is best in the nature of the observers, while the graphic and eloquent word-pictures of our leader should tinge with colour, as with the hands of an artist in studies of human nature, these pictures, which all but speak their own story. May God’s spirit be poured upon lecturer, operator and audience alike!’ (MWC 15/9/00) p8)

TRANSPORT

Part of this thrill was also a sense of transport, to take the audience out of their seats in Melbourne, and into another spatio-temporal realm. As Booth promised:

I have sought to make everything absolutely correct. From the plumes on the Roman helmet and the imperial robe of Nero to the rough garments of the pagan slave, everything will be exact. You only have to follow the screen and you will be as much in Rome as if you had been there – now in the palace of Caesar, then in the open square – now in the residence of the patrician, then in the den of the libertine — now in the coliseum then in the Catacombs, where the early Christians concealed themselves for safety — all will be absolutely exact’ (MWC 18/8/00 p9)

This is very similar to the promises which had been made by stereograph manufacturers since the 1850s. By the 1900s sellers like Underwood and Underwood were marketing complete ‘Travel Systems’ incorporating, stereographs, guidebooks and maps, to give a similar, touristic sense of optical and retinal transport.

But to the Army audience this transport was more than just virtual tourism, it was transport of a more profound kind. A later report on a limelight meeting said:

the meeting almost becomes as a séance, and our spirits seem to blend with the spirits of these just ones.’(MWC 9/2/01 p9)

AFFECT

Was Soldiers of the Cross effective? The War Cry frequently reported on the ‘involuntary interjections, moans of pity, sighs of relief’ coming from the audience. (MWC 29/09/00 p8) All the Army reports are ecstatic, but they would be, wouldn’t they. However even the hard-bitten seen-it-all mainstream press confirmed the affective power of the production. The premiere scored a review from two out of the three of Melbourne papers, and both used the word ‘thrilling’.

The Age said:

To have some of the most tragic episodes of Christian history carried out in all savage but ?should? destroying realism is an accomplishment essentially of today. It was done by the aid of the kinematograph, when Commandant Booth delivered his thrilling lecture last night.

The Argus said:

Opening with the last days of the life of Christ, Commandant Booth dealt with the lives of the disciples [… ] and the thrilling scenes that were enacted in the arena of the Coliseum. Bold as the lecture was in conception, the illustration were even more daring. (MWC 22/9/09)

CONCLUSION

Soldiers of the Cross is extremely important because it was Australia’s first large scale multimedia production. On at least several occasions it kept close to 2000 people simultaneously enthralled by a production that was experientially integrated over an entire two and a half hour period. It innovated on narrative formats from the nineteenth century, and incorporated technology that would come to dominate the twentieth century. It created an entirely new experience by weaving familiar visual forms and technological experiences in with established viewing protocols and ritualized behaviours that had been developed and inculcated into Australian audiences during the previous five decades. The scale and the complexity of the integration of these experiences looked forward to twentieth century media forms. One of those media forms was certainly the cinema, but others include the history of the lantern itself which continued in parallel to cinema for another five decades, as well as much later media forms such as broadcast radio and television, and even, at a stretch, contemporary digital media platforms. For these reasons it is an extraordinarily important event in Australian history. Much more important than we first realized.

Martyn Jolly