‘Before Carol, Australian photography of the 1960s’,

Carol Jerrems symposium, National Gallery of Australia, 8 September 2012. The images that accompanied the presentation can be found below the text as either a PDF or a Powerpoint

Before I begin I’d like to thank the National Library of Australia, who gave me a fellowship to do some of this research, and Gael Newton, who gave me access to some of her research materials.

As the great Shirley Strachan once put it, I feel a bit like ‘I’m in a payphone without any change’ standing up here, because I don’t really have very much to add to the discussion of Carol Jerrems. I think many excellent people have done a lot of excellent work on Jerrems and her milieu, and I don’t really have a problem with any of it. The only thing I do have a slight problem with is: whatever happened to the sixties? Even though Jerrems did her art school training in the closing years of the sixties she is rightly seen as the quintessential seventies photographer. But, too often I think, the early seventies, of which Carol is the preeminent photographer, is seen to be the Edenic origin of contemporary Australian art photography, with the decade before being simply some undifferentiated primordial slime of bad commercial and worse amateur photography. There certainly was a lot of bad photography in the sixties, but it wasn’t all undifferentiated slime.

It’s understandable why this view would slowly become the norm. All of the infrastructure which we still more or less enjoy — the galleries, the collections, the funding — began in either the very late sixties or the very early seventies. 1968: The Australian Council for the Arts established. 1972: the NGV photo department commenced, and Rennie Ellis’s Brummels Gallery opened. 1973: the Australian Centre for Photography opened. 1974: four, count them, four books of Australian photography came out, two in Sydney published by the brand new government funded Australian Centre for Photography, and two in Melbourne published, with the assistance of Australia Council grants, by Outback Press, a small start-up publishing company which had emerged out of Melbourne University student publications, and which also published poetry and politics. The two ACP books classily surveyed the extraordinary efflorescence over the previous couple of years of purely ‘personal’ photography by the new generation of art school trained photographers; while the two books by Outback Press combined the photography of two of that new generation with new writing. Into the Hollow Mountains combined Robert Ashton’s photographs of Fitzroy with poems and experimental literature about the suburb by the likes of Helen Garner; while A Book About Australian Women combined the writing of Virginnia Fraser with the photographs of Carol Jerrems

In her 1973 application to the Visual Arts Board Jerrems had said of the proposed book:

The emotions, attitudes, sexuality and intellect of Australian women through the eyes of women has not been considered in the anticipated format, and a greater depth will be achieved by going beyond the single picture concept, and by intermeshing of photographs and words concerning themes personally experienced by the artists involved.

In the end however, as was the case for many other picture books before them, the words and photographs weren’t as enmeshed as the grant application had envisaged. Rather than in tandem, Fraser and Jerrems worked separately on their sections, which were alternated on different paper stock throughout the book. But in her layout for her sections, printed on glossier, thicker stock than Fraser’s, Jerrems certainly did go ‘beyond the single picture concept’, with cinematic sequences of shots being laid out like frames from a film. The sister book, Robert Ashton’s Into the Hollow Mountains, also separated text and word. But although, like Jerrems, Ashton also experimented with multiple picture layouts, he didn’t do it as consistently as she had. Jerrems even retained the book’s layout unchanged when she worked on the wall for the Brummels exhibition the two held together at the launch of their respective books.

In the years before the book came out Jerrems had had the opportunity to experiment with multiple picture layouts when she contributed several photo series to the Melbourne University magazine Circus, on which the publishers at Outback Press cut their teeth. For instance in the final issue of Circus Jerrems interspliced the photoseries Hanna, about Ross Hannaford, with the Photoseries Hanging About, with Pearl, and in addition, experimented with repeating the image from the previous page in Hanging About, with Pearl as a kind of thumbnail afterimage on each new page.

A year after A Book About Australian Women, Jerrems worked on a much smaller scale for the cheap, hip-pocket sized paperback, Skyhooks: Million Dollar Riff. Jerrems’ sections of back-stage photographs, again printed on gloss stock and bound in between Jenny Brown’s prose, retained the same sequential layout structure as her previous work.

The popularity of these small paperbacks had been promoted in the sixties by publishers such as Sun books. There were a wide variety of book experiments being undertaken in the late 1960s, as small publishers jostled against each other for new angles onto the market. Even film tie-ins were experimented with. In 1968 Tim Burstall made a semi-autobiographical feature film about a creative young man feeling stultified by, but bound to, Australia. Called Two Thousand Weeks, the film bombed at the box office, with audiences rejecting its subject matter and European art-house stylings as self-indulgent and pretentious, so probably the accompanying photo-roman produced by Mark Strizic bombed in the bookshops as well, even though in the tiny arena of the double page spread Strizic tried to integrate film dialogue and sequential photographs in a new way.

A Book About Australian Women, produced during the international year of women, and launched by Margaret Reid, Australia’s first commissioner for women, was a feminist project. But it was intended to be feminism from the ground up, through the eyes and the mouths of as wide a range of women themselves as possible. Had women been considered before in Australian photography, if not quite in Jerrems’ anticipated format of ‘themes personally experienced by the artists involved’? Well, yes they had. By way of complete contrast I can’t resist taking a cheeky look at the Sydney photographer David Mist’s Made in Australia, which in 1969 stole an idea from a 1967 British book called Birds of Britain. It responded to the emerging independence and self-assertion of women throughout the 1960s by packaging up different young Australian women into a useful compendium aimed at the aspirational, cravat-wearing, bachelor-playboy market. The Outback Press books were cheap, cheap, cheap, printed cut-price at a suburban newspaper and imperfectly bound so that they fell apart almost immediately. Mist’s book, on the other hand, was printed in Hong Kong by the British publisher Paul Hamlyn who was seeking new angles to access what was a very healthy Australian market for books about contemporary Australia.

However in 1969, the same year as Made in Australia came out and was launched by Patrick MacNee, the dapper star of the 1960s TV series The Avengers, another major international publisher with offices in Australia, Nelson, published a series of feminist essays on the new 1960s woman called In Her Own Right. This book, well bound and printed in Hong Kong, was edited by Julie Rigg, and illustrated with photographs by the unknown photographer Russell Richards. Perhaps it was the visual approaches of books such as these that Jerrems had in mind when, four years later, she counterposed against them the ‘greater depth’ of her multiple picture approac’ taken as though through the eyes of women themselves. However, amongst the stilted studio shots that illustrate In Her Own Right’s essays there were also long-lensed portraits taken in photojournalistic style. These, in their frankness and frontality, are effective; even if they convey no sense of the personal connection or warmth feminist photographers like Jerrems were to seek for later.

The unnamed designer of Julie Rigg’s book had clearly been greatly influenced by the single most important book of the 1960s, The Australians, which was still a best seller in 1969 three years after it was first published. Shot by a hot-shot National Geographic photographer called Robert Goodman, and funded by the mining and tourism industries, The Australians dominated the photographic landscape well into the 1970s and initiated a slew of imitations, such as the design and photography of In Her Own Right.

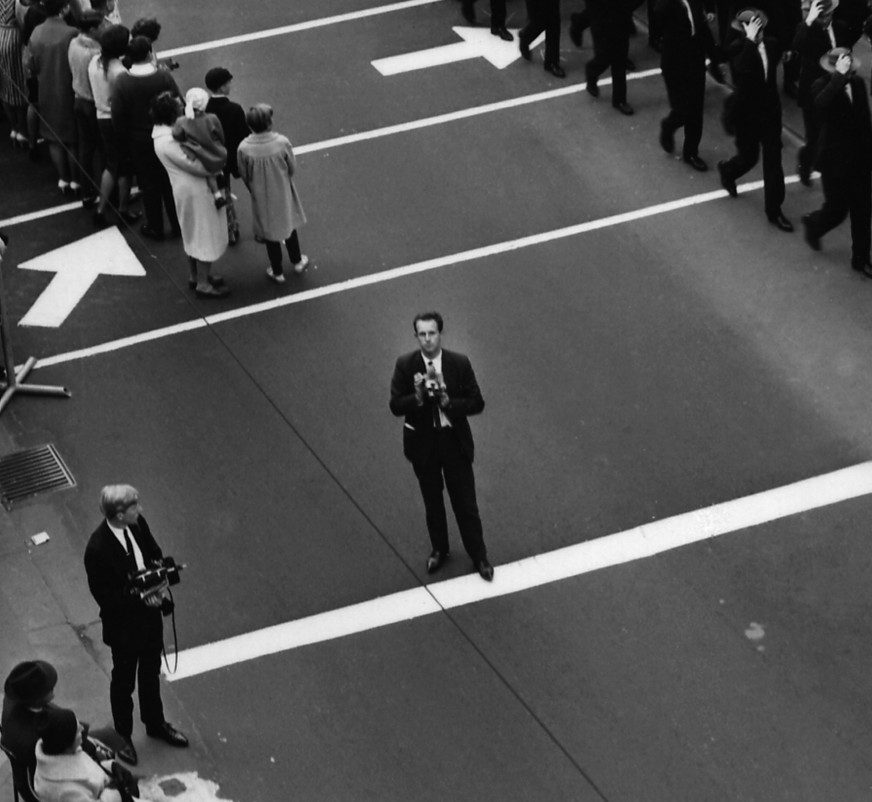

If the ‘new woman’ was a major topic in the late sixties and early seventies, ‘woman’ in general had become a category of mainstream interest even earlier. In the early sixties a group of three male amateur photographers, Albert Brown, George Bell, and John Crook, broke away from the camera club movement and formed their own group called Group M. They were particularly inspired by the Museum of Modern Art’s Family of Man exhibition that had finally made it to Melbourne in 1959. In 1963 they staged an exhibition of their work in the Melbourne Town Hall under the theme Urban Woman. Like the Family of Man it was arranged from youth to age, but it failed to get close to its subject, relying on telephoto lenses. Even the woman invited to open the show, Myra Roper from Melbourne University’s Women’s College, complained that: ‘a lot of the pictures show women just waiting — waiting for buses, waiting in queues, or waiting for a man to finish his tea.’

Because of exhibitions such as this and books like The Australians, the long-lensed street-shot became a major trope of late sixties photography; so much so that, in talking to the journalist Craig McGregor for Men Vogue in 1977 Jerrems told him that, because she was looking for sympathetic warm portraits, she did not use a wide-angle lens because it distorted, nor a telephoto lens because, to quote her, ‘it seems like you should have walked up closer’.

Jerrems’ period, the early 1970s, came immediately after a period from the mid sixties on when there had been a real thirst for photography books about Australia. The sixties were a period of economic boom because of mining and manufacturing, and a period of social transformation because of wealth and immigration. While there were only a handful of feature films made during the period, there were tens upon tens of picture books published. If the main topic of the 1970s was the personal — personal relationships, personal politics, personal journeys, personal spiritual experiences — the main topic of the 1960s was national identity — what was an Australian, what did they look like, how were they different to other nationalities, what was special about them, how did they collectively define Australia? (When this national 1960s anxiety persisted into the 70s it was usually as caricature or parody.) The new publishers of the 1970s, like Outback Press, followed on from their start-up predecessors in the 1960s, like Sun books, by also being small, lean, front-room publishing operations. But they differed from 1960s publishers because they were able to produce even cheaper large-format offset paperbacks for distribution, as well as apply for government grants to support their books.

It was the journalist Craig McGregor who had first suggested the idea of In Her own Right to Julie Rigg, and who had covered the new generation of Australia photographers, including Roger Scott, John Williams, Richard Harris, Wesley Stacey and Carol Jerrems for Men Vogue. In the same year he used a detail from Vale Street on the cover of his novel The See-Through Revolver. In the 1960s McGregor had written books attempting to statistically measure Australian society and define Australian identity as a whole, but he also had sympathy for the kind of intensely personal experience that characterized the 1970s. In 1968 he worked with Helmut Gritscher on the photobook To Sydney With Love. The photographs themselves were prosaic, but they allowed McGregor the opportunity to attempt a very personal beat-poetry meditation on Sydney that predicted the expressionistic writing of the 1970s. Unusually for the period, he opened the book’s text with his experience of a late night epiphany standing on the roof of a block of flats in Potts Point looking into Woolloomooloo:

I know this city, I comprehend it utterly, my guts and mind embrace it in its entirety, it’s mine. It was a moment of exhilaration, of exquisite and loving perception, my soul stretched tight like Elliot’s across this city which lay sleeping and partly sleeping around me and spread like some giant Rorschach inkblot to a wild disordered fringe of mountains, and gasping sandstone, and hallucinogenic gums.

The two Outback Press photobooks of 1974 both concentrated on Australia’s social and political demimonde, as well as on notorious areas of urban pressure and social change. In fact a poem by Peter Oustabasadis on the final page of Into the Hollow Mountains, complained about the very process of groovy gentrification that the book itself was part of:

Get out of Fitzroy/ you’ve side-stepped the blood pools/the pus holes &/raised the rents/classed the restaurants/closed down the hamburgers/gouged the stomachs out of houses/& photoed the bedrooms of drunks/you’ve made this place hell/WE’LL BURN THE STREET SIGNS/we know our way around

But other earlier books had identified similar sub-cultures and potent urban sites. For instance in 1965 the poet Kenneth Slessor and the photographer Robert Walker produced the first picture book about Kings Cross. It was pretty boring, but six years later Rennie Ellis and Wesley Stacey produced a much more vivid and lively portrait published by Nelson, the same publisher as In Her Own Right. Kings Cross Sydney: A Personal look at the Cross by Rennie Ellis and Wesley Stacey, 1971, used the double page spreads of the book in a graphically exciting way, and took the reader into the dressing rooms of Les Girls, as well as into the bedrooms of junkies.

Institutionally, sixties phtography was dominated by two major formations. The Institute of Australian Photographers, represented the commercial photographers — the industrial, illustrative, fashion and advertising photographers; and the Australian Photographic Society, representing the amateurs — still largely pursuing Pictorialism through their camera clubs. By the late 1960s and early 1970 this photographic divide had produced two distinctive strands when it came to the category of ‘creative’ photography, both of which relied on very high contrast printing. The 1972 book Concern: The Ilford Photographic Exhibition showcased both approaches. The overall winner of the competition to address the theme of ‘concern’, who walked away with prize money of $1000 and a round the world plane ticket for two, was Barrie Bell. He had submitted four gritty street-drunk shots, which were well and truly clichéd even in 1972. A photographer with Melbourne’s Channel 9, Bell took the opportunity to defend his patch against the prominence of the new generation of personal photographers, he said: ‘I hate to see photography abused, particularly by those with no professional training, offering photography from a backyard, doing poor stuff, taking work from the pro, and giving photographers and photography a bad name.’ There were other more effective photographs from this genre of gritty realism in Concern, for instance Rennie Ellis submitted four junkie photographs from the Kings Cross

The other dominant ‘creative’ style during these years was a quasi-surreal, darkroom crafted, graphically designed, high-contrast negative composite. This style had been showcased three years before Concern in 1969, in a publication from the Melbourne University Photography Club called Spilt Image. With layout design by Suzanne Davies, it juxtaposed experimental short stories with photo-sequences that were described by the Melbourne Herald at the time as ‘quite sick’, “way out”, and ‘weird’. The style was represented again in Concern by the Gordon de’Lisle with a series that attempted ‘to show the raped land, Australia, as it would appear to a woman who returns from the dead to discover that her country, too, is dying.’ (Although why the woman is beautiful and nude, de’Lisle didn’t explain.) Paul Cox, Carol Jerrems’ mentor at Prahran CAE, straddled both well-worn genres with three sets of photographs accepted into Concern — negative double exposures, window lit portrait tableaus, and journalistic travel photographs. A year earlier Cox too, like Stacey and Ellis, and Julie Rigg, also produced a book with the publisher Nelson. His was based on two trips to New Guinea, described by him in his autobiography as ‘a romantic journey in search of man’s childhood’. In Home of Man: The People of New Guinea his high contrast images were juxtaposed by the writer Ulli Beier with poetry by New Guinean students.

So the few years around 1974 were certainly a watershed for Australian photography. Even looking forward one year to 1975 we have the publication of the crucial and very sophisticated book Green Bans by Marion Marrison and Peter Manning, published by the Australian Conservation Foundation; as well as the first of the widely popular Rennie Ellis books, Australian Graffiti. And by the late seventies, of course, museums were collecting heaps of photos and the boom was well and truly on. However, clearly, any direct causality between the Australian photography of the 1960s and that of the 1970s was minor, obviously what was happening in the US and to a lesser extent the UK was far more important to Jerrems and her generation. But nonetheless if we widen our scope out from just gallery exhibitions and museum collections to books and magazines we can see that the transition in Australia itself was not from nothing to something, but from something to something else.

During the transition the telephotos and fisheye lenses were dropped; the contrast of photographic paper went down from grade 4 and 5 to grade 2 and 3; the darkroom faux-surrealism and neo-pictorialism by-and-large faded away — at least until the invention of Photoshop; and the figure of the personally expressive photographer became central to progressive Australian art and culture, not marginal to it. But, lest we forget, there were at least a handful of important Australian photography books published before that key date, back in the mid to late sixties.

Martyn Jolly

Click here for a PDF of the pictures:

Click here for a Powerpoint of the pictures:

Martyn, I stumbled over this, skim read it (am about to slow read it) and was riveted. Brilliant and necessary.

LikeLike

Thank god (if there is one apart from the Sunny Sixteen Rule) for researchers like you who dare to question the assumptions we all hold dear. I sincerely hope Gordon de’Lisle is rolling (and rocking) in his grave.

LikeLike