The Belief in Spirit Photography

‘Faces of the Living Dead’, lecture, Centre for Contemporary Photography, Melbourne, November, 2002.

In Britain in the 1920s a group of Spiritualists formed the Society for the Study of Supernormal Pictures. They were convinced that spirit photographers were able to capture images of the dead returning from the other side to be photographed with their loved ones. Their belief was disputed by the Society for Psychical Research, a society (that exists to this day) that dedicated itself to the objective scientific investigation of paranormal phenomena. The SPR successfully exposed as frauds several spirit photographers supported by the SSSP.

To members of the SPR, once exposed as fakes spirit photographs could be only one thing, incontrovertible evidence not of spirit return, but of human stupidity. However recently the student of photographic culture, rather than psychic phenomena, has become interested in spirit photographs. Historians, curators and artists have realized that although ‘fakes’ on one level, they nonetheless remain powerful photographic evidence on another level. They now speak to us more strongly of faith, desire, loss and love than gullibility. They raise new questions: not are they fake or are they real, but how and why did they come to be made, and what did they mean, emotionally, to the people who once treasured them? Looking into these portraits now their fakery seems crude and self-evident, but if we keep on looking another very real quality emerges from the faces of the people who were photographed — their ardent desire to see and touch a lost loved-one once more.

In the late nineteenth century and early twentieth century the advances of modernity seemed to offer to the people in these photographs the incredible possibility that the eternal desire to communicate with the departed might finally be realizable. The belief in this possibility was called Spiritualism. Modern Spiritualism traced its origin back to one day in 1848, when two young sisters apparently began to here mysterious rapping noises in their house in upstate New York. They supposedly worked out a simplified Morse code by which they could rap back questions to the spirit who haunted the house, and receive answers. The two girls, Kate and Margaret Fox, went on to become Spiritualism’s most famous mediums, holding séances throughout the US and the UK for the rest of the century. Many other mediums, professional and amateur, also began to hold private and public séances. At these séances the mediums would communicate with the dead through raps, or they would fall into a trance and, supposedly under the control of an intermediary spirit guide, speak in the voices of spirits who had messages for the living. As the ranks of believers in these phenomena swelled, they formed themselves into associations and churches and Spiritualism became a widespread social movement. [i]

But it is not only the elaborate paraphernalia of Spiritualism that makes spirit photographs continue to be so compelling for us now, it is something about the essential nature of photography itself. Photography stops an image of a living person dead in its tracks, and peels that frozen image away from them. In this sense all portrait photographs are spirit photographs because they all allow us to see, and almost touch, people as they lived in the past. The people in these images, once so desperate for an image of their deceased loved ones, are now themselves all dead also, but ironically revenant in their portraits. Perhaps we too can almost reconnect with them, in a way not dissimilar to their own attempts to reconnect with those on the other side of the veil.

One of Spiritualism’s most energetic and public converts was the notorious reformist journalist and publisher William T. Stead. In 1893 Stead re-published a report on spirit photography in his popular magazine, the Review of Reviews. The report was by the editor of the respected professional publication the British Journal of Photography, J. Traill Taylor. Taylor was also a Spiritualist who had been investigating spirit photography since the 1860s. Although he was convinced that the phenomenon was genuine, he had to admit to his more sceptical photographic colleagues that the spirit figures, which were called ‘extras’, behaved badly before the camera. Some were in focus, others not. Some were lit from the right, while the living sitter was lit from the left. Some monopolized the entire plate, obliterating the sitter, while others looked as though they had been cut out of another photograph by a can-opener and held up behind the sitter. In addition, when photographed with a stereoscopic camera the spirits appeared in two dimensions, not three, and were out of alignment on the stereo plates. This led Taylor to the conclusion that the images were produced without the aid of the camera, at some other stage in the process than the initial act of portraiture. ‘But still the question obtrudes, how came these figures there? I again assert that the plates were not tampered with, by either myself or anyone present. Are they crystallizations of thought? Have lens and light really nothing to do with their formation?’[ii]

For the Spiritualists one fact again and again dispelled all the doubts and ambiguities that surrounded spirit photographs — that fact was the incontrovertible thud of recognition they felt in their chests when the belief that they were seeing a familiar face once more hit home. During this period big companies such as Kodak were marketing their cameras by heavily promoting the mnemonic value of amateur family snapshots, and more and more people were able to afford regularly updated professional portraits for their family albums. Amateur and professional photographs were gaining new authority as the prime bearers of family memory. The photographic portrait became an even more intense arena for experiencing, nurturing and sharing feelings of affection and connection. In this context, when the spirits revealed, through the voices of the mediums, that they had specific emotional and filial motivations for appearing within the family portrait, the act of recognition was sealed even more strongly onto the amorphous face of the extra.

At a séance the medium was controlled by the spirit of a woman who had returned to her husband as an extra on spirit photograph of him. She tried to explain the process by which spirits such as herself established an ethereal connection back to our side of the veil through the force of spirit memory itself.

When we think of what we were like upon the earth, the ether condenses around us and encloses us like an envelope. […] our thoughts of what we were like, and what we would be better known by, produce not only the clothing, but the fashioning of the forms and features. It is here that the spirit-chemists step in […] using their own magnetic power over the etherealised matter [they] mould it so, and give to it the appearance such as we were in earth life.[iii]

One Saturday afternoon in 1905 a carpenter from the English town of Crewe was experimenting with photography with a friend. To his surprise on one of the plates he found a transparent form, through which a brick wall remained visible. The friend recognised it as his sister, who had been dead for many years. Shortly afterwards the carpenter, William Hope, formed a séance circle with the medium Mrs Buxton, the wife of the organist from the Crewe Spiritual Hall. The circle concentrated on spirit photography, with Hope photographing in a ramshackle glasshouse behind his house. Hope and the Crewe Circle came into their own immediately after the First World War, when the world was swept with a new craze for Spiritualism following the immense combined death-toll of the war and the influenza epidemic. Their work was eagerly examined, promoted and endorsed by the SSSP

If clients made the pilgrimage to Crewe, Hope charged four shillings sixpence for a dozen prints, based on his wages as a carpenter. As his fame grew he regularly travelled to London to hold sittings at the imposing premises of the British College of Psychic Science. The BCPS had been set up in opposition to the SPR in 1920. It was owned by Mr and Mrs McKenzie, two zealous promoters of Spiritualism who had lost their son to the war. They charged two guineas for a sitting with Hope. For some reason spirit extras eschewed the multi-exposure roll-film cameras that were becoming standard in the post-war period, and would only appear on glass-plates in old-fashioned plate-holders, where each negative had to be individually handled by the photographer. On departure sitters signed an agreement indemnifying the BCPS against any legal action. And they were not allowed to take the negatives from the premises.

The famous creator of that arch-rationalist Sherlock Holmes, Sir Arthur Conan Doyle, had been a jingoistic propagandist during World War One. Following the deaths of his brother and his eldest son, Kingsley, as a result of wounds received in the war he became an evangelical Spiritualist. He used his wealth and fame to proselytise the cause in bluff pugnacious lectures delivered from platforms across the world. In 1920 and 1921 he spoke to 50,000 people in Australia alone. He was feted by Spiritualists, and criticized by churchmen, while he lobbied the press and courted politicians. He was even occasionally attended by the odd unexplainable psychic phenomena of his own. In Brisbane, for example, he showed his good will by investing £2000 in Queensland Government Bonds. The government photographer turned up to take his portrait handing over the cheque on the steps of parliament house, but Sir Arthur was obscured by what appeared to be a cloud of ectoplasmic light on the plate. Doyle’s equable comment was:

I am prepared to accept the appearance of this aura as being an assurance of the presence of those great forces for whom I act as humble interpreter. At the same time, the sceptic is very welcome to explain it as a flawed film and a coincidence [iv]

Conan Doyle’s lectures provided implicit comfort to the bereaved. The Melbourne Age reported: ‘Unquestionably the so-called ‘dead’ lived. That was his message to the mothers of Australian lads who died so grandly in the War, and with the help of God he and Lady Doyle would ‘get it across’ to Australia’.[v] In the context of collective post-war grief the spirit photographs that Doyle projected worked in quite a different way, in their open-endedness, to the monumental and mute funeral portrait. In 1919 the Australian Spiritualist newspaper Harbinger of Light took delight in quoting the Rev. T. E. Ruth, the minister of the Collins Street Baptist church, Melbourne:

I have been impressed by the fact that [spiritualist literature] has been concerned with the practical comfort of mourning multitudes, while ordinary church papers have been almost as deficient in spiritual consolation and guidance as that dreadful ‘In Memoriam’ doggerel about there being nothing left to answer but the photo on the wall.[vi]

Doyle was one of the vice-presidents of the SSSP, and a key promoter of Hope. He went to Hope to obtain a photograph of his fallen son, and published the resultant image in newspapers and magazines around the world. The Sunday Pictorial reproduced the photograph flanked by a photographic reproduction of Doyle’s handwritten testimony:

The plate was brought by me in Manchester. On reaching Mr Hope’s studio room in Crewe, I opened the packet in the darkroom and put the plate in the carrier. I had already carefully examined the camera and lens. I was photographed, the two mediums holding their hands on top of the camera. I then took the carrier into the darkroom, took out the plate, developed, fixed and washed it, and then, before leaving the darkroom, saw the extra head upon the plate. No hands but mine ever touched the plate. On examining with a powerful lens the face of the ‘extra’ I have found such a marking as is produced in newspaper process work. It is very possible that the whole picture, which has a general, but not very exact, resemblance to my son, was conveyed onto the plate from some existing picture. However that may be, it was most certainly supernormal, and not due to any manipulation or fraud.[vii]

Spiritualism was always followed for selfish reasons. It was not concerned with the transcendently numinous, so much as the immediate desires of each individual soul for solace. When, in 1888, forty years after they began modern Spiritualism, the Fox sisters publicly confessed to their childhood fraud in front of a packed house at the New York Academy of Music, Spiritualists throughout the house cried out at having to face again the loss of loved ones they thought restored to them for ever.[viii]

Although the product of extreme credulity, spirit photography was nonetheless a collective act of imagination which in many ways was no more than an amplification of the way normal photographs were coming to be used every day in people’s habitual processes of remembering and mourning. In many ways spirit photographs served the same function as precious family photographs. But they were not snapshots of passing events, rather, they were the central magic objects in elaborate rituals and performances. They didn’t find their truth in the documentation of a prior reality, they created their truth within the wounded psychology of their audience. Their truth was manifested and sealed by the undeniable thud of recognition viscerally felt by the customers for whom they were made.

The power of the spirit photograph was not built around the conventional mechanism of the snapshot — the camera, the lens and the shutter. Instead it was compressed into the sensitive photographic plate alone. Photographic emulsion was imaginatively linked to ectoplasm and activated as a soft, wet, labile membrane between two worlds — the living and the dead, experience and memory. The spirit photograph’s emulsion was sensitised chemically by the application of developers, and psychically by the meeting of hands and the melding of mutual memories. No spirit photographer exemplified this better than Mrs Ada Emma Deane, who joined William Hope on the British Spiritualist scene in 1920.

Late in 1920 Deane visited the Birmingham home of Fred Barlow, secretary of the SSSP, to submit herself to a series of tests and experiments. He had supplied Deane with a packet of photographic glass-plates two weeks before the tests for her to pre-magnetize them to psychic impressions by keeping them close to her body. On development, the portraits Deane took held the faces of psychic extras swathed in chiffon-like and cottonwool-like surrounds. ‘It appears’, Barlow reported, ‘as though the plates in some peculiar way became impregnated with the sensitive’s aural or psychic emanations’.

If Barlow was seeking any further proof that Deane was genuine he found it a year later in August 1921. In the interim his father had died, and in the last solemn moment of his father’s earthly life Barlow’s repeated but unspoken cry was: ‘Father, if it is possible, come back and prove to us that you still live.’ Barlow’s young female cousin was visiting the family, and at a home séance Barlow’s father manifested himself and told her, ‘Don’t return home yet — stay on a little longer!’ The following day Deane and her family arrived to spend their August holidays with the Barlows. After a short religious service, Deane photographed Barlow’s cousin, who had taken the spirit’s suggestion and decided to stay on. On one of the plates they secured as an extra a likeness of Barlow’s father which was immediately recognised by all of the family as very similar to how he had appeared during the last moments of his earthly life. Barlow concluded: ‘Our would-be critics are silenced! How can they be otherwise in face of perfect proof, such as this, which week by week is steadily accumulating?’[ix] A year or so later Barlow and three sceptical friends motored to Crewe for a sitting with Deane’s fellow spirit photographer William Hope. They disturbed the family at tea, but Hope agreed to make some exposures by magnesium light. The four received as an extra an image of Barlow’s father that was identical with an extra previously received on Deane’s plate.

But, rather than evidence of collusion, Barlow speculated that this duplication was because the subconscious portion of his mind was being employed to project, or print, the picture onto the plate. But how was the psychic investigator to know whether the images he was examining originated entirely in the mind of the sitters, or whether their unconscious minds had become instruments used by the invisible operators for the production of phenomena originating on the other side?

Is it blind or automatic intelligence that sends these photographs in response to the prayers of the widow and the cry of the mother for proof that the dead still live. Are they just brain freaks? Chemical results produced by ourselves to deceive ourselves? Man’s commonsense and woman’s intuition revolt against such a likelihood. In many instance we see clear evidence that other minds are at work, distinct from and often superior in intelligence to those of medium and sitters. These intelligences claim to be the so called dead. They substantiate their claims by giving practical proof that they are those who they purport to be. In no uncertain voice they claim to be discarnate souls. Surely they ought to know![x]

The Occult Committee of the Magic Circle also tested Deane and found the sealed packet of plates they sent to her for pre-magnetisation had been tampered with. (See Figure 89) But without hesitation Doyle, who had sat for Deane himself and got a female face smiling from an ectoplasmic cloud, (See Figure 90) sprang to her defence:

The person attacked is a somewhat pathetic and forlorn figure among all these clever tricksters. She is a little elderly charwoman, a humble white mouse of a person, with her sad face, her frayed gloves, and her little handbag which excites the worst suspicions in the minds of her critics.[xi]

F. W. Warrick, the wealthy chairman of a of wholesale druggist firm, became progressively obsessed by Deane and her predominantly female household. Over eighteen months from 1923 to 1924 Warrick visited Deane’s house twice a week for personal sittings during which she exposed over 400 plates, mostly of Warrick himself. Deane’s seemingly ingenuous personality immediately convinced him that her psychic powers were real, a view he never wavered from even after 1400 inconclusive experiments with her. He assured Dingwall:

She makes no profession of honesty, but she is just honest. […] Mrs Deane is very friendly towards me. I now know her family well and have entree to their kitchen and scullery. I am perfectly convinced that Mrs D. practices no fraud. I admire her character and the sturdy independence of her spirit. She is not ‘out for money’.[xii]

Nonetheless Warrick imposed increasingly rigorous conditions on his experiments, cunningly sealing the packets of plates he gave to Deane for pre-magnetisation, and insisting on using his own camera and, most importantly, plate-holders. Although, as he admitted to Dingwall, the imposition of these stringent conditions resulted in the departure of the veiled extras, he determined to go on as long as Deane was willing, and his opinion of her remained the same. He switched his attention from the extras to the multitude of ‘freakmarks’ — chemical smudges and smears, and bursts of light — which appeared on her plates. These further investigations were also fruitless, but they did eventually lead him to undertake another 600 inconclusive thought transference experiments on Deane over the next three years. These tested her ability to write letters on sealed slates and to make marks on pieces of cartridge paper placed against her body. For the purposes of these experiments Warrick had Deane and her family move into a house he owned. One room was reserved for séances and a darkroom was built into it, as well as a small sealed cabinet for the thought transference experiments. Whilst Deane sat in the cabinet with her hands imprisoned in stocks, Warrick crouched outside and attempted to transmit his thought images to her.

Warrick scrupulously recorded all of his experiments. In the tradition of previous obsessive psychic researchers he compiled and published them, along with his extended but inconclusive reasoning as to what they might mean, in a monumental 400 page book. She gave him access to her negative collection and he had 1000 of them printed up and bound, in grids of twelve per page, into four large albums, embossed with her name, which he presented to her. He asked the Society for Psychical Research to be responsible for their eventual preservation because, ‘the prints may be of great value — and may be sought after the world over for the purposes of study. They are unique in the world.’[xiii]

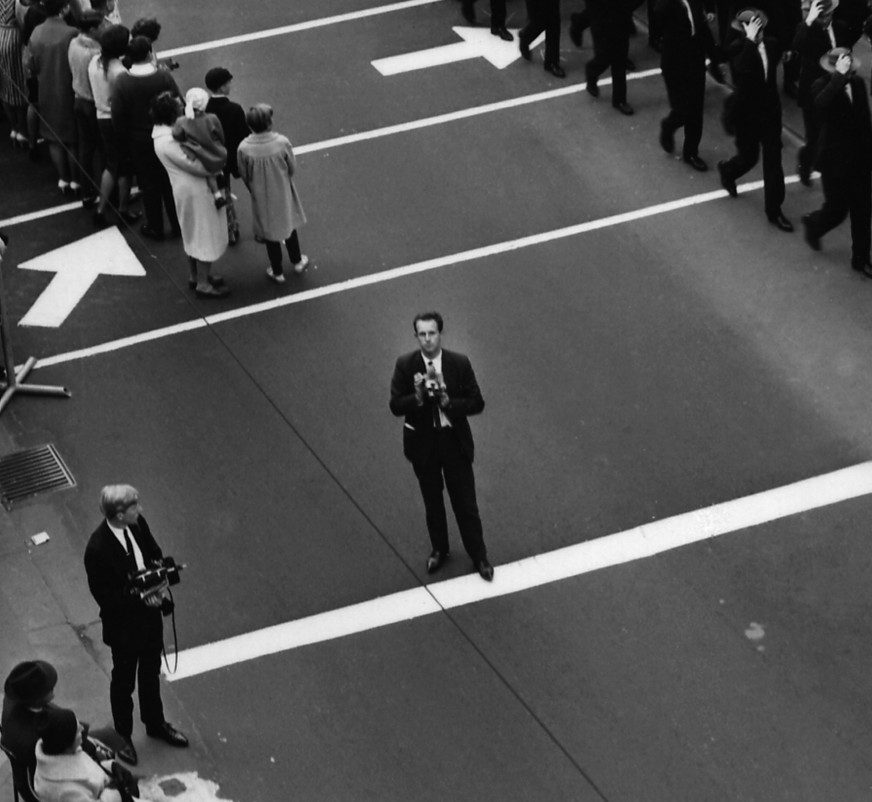

Deane’s greatest fame came in the mid 1920s through her involvement with Estelle Stead, another eminence of the Spiritualist movement who ran a Spiritualist church and library called the Stead Bureau. Estelle Stead was the daughter of the W. T. Stead who had been photographed in the 1890s with the ‘thought mould’ extra of his spirit guide Julia. Stead was clairvoyant, but this faculty didn’t prevent him from booking a passage on the maiden voyage of the Titanic. Shortly after he drowned, however, his spirit reappeared at a London séance and continued his Spiritualist activities as busily as ever. In 1923 Estelle Stead received another ‘wireless message’ from her father that they should arrange for Deane to take a photograph in Whitehall during the Two Minutes Silence that year. A group of spiritualists were placed in the crowd to produce a ‘barrage of prayer’ and so concentrate the psychic energy, and Deane took two exposures from a high wall over the crowd, one just before the Silence, and one for the entire two minutes of the Silence. When the plates were developed the first showed a mass of light over the praying Spiritualists, and in the second what was described by the discarnate W. T. Stead as a ‘river of faces’ and an ‘aerial procession of men’ appeared to float dimly above the crowd. The images were commercially printed together and distributed amongst Spiritualists.

Conan Doyle took this image with him on his second tour of America, which featured an entire lantern-slide lecture on spirit photography. In April 1923 he lectured to a packed house at Carnegie Hall. When the image was flashed upon the screen there was a moment of silence and then gasps rose and spread over the room, and the voices and sobs of women could be heard. A woman in the audience screamed out through the darkness, ‘Don’t you see them? Don’t you see their faces?’, and then fell into a trance.[xiv] The following day the New York Times described the picture on the screen:

Over the heads of the crowd in the picture floated countless heads of men with strained grim expressions. Some were faint, some were blurs, some were marked out distinctly on the plate so that they might have been recognised by those who knew them. There was nothing else, just these heads, without even necks or shoulders, and all that could be seen distinctly were the fixed, stern, look of men who might have been killed in battle.[xv]

Two more photographs were taken during the following year’s Silence. Although the heads of the fallen were impressed upside down on Violet Deane’s plate, the pictures were circulated through the Spiritualist community. Many people recognised their loved ones amongst the extras, and those on the other side often drew attention to their presence in the group. H. Dennis Bradley, for instance, was in contact with the spirit of his brother-in-law who told him, through a medium, that he was, ‘on the right-hand side of the picture, not very low down’. On the following day Bradley obtained a copy of the photograph and, to his astonishment, among the fifty spirit heads visible in the picture he found one in the position described which, under the microscope, revealed a surprising likeness to his deceased brother-in-law.[xvi] A Californian woman, Mrs Connell, received a copy of the picture from a friend. Intuitively feeling that it might be meant for her particularly, she got out her ouija board to communicate with her fallen son David. She asked him if he was in the picture. ‘Yes’, he said, ‘to the right of Kitchener’. She found Lord Kitchener’s face and there, to the right of it, was a face she recognised as her son’s.[xvii]

At her discarnate father’s suggestion Estelle sent copies of the two photographs to the medium Mrs Travers-Smith asking her to submit them to her spirit guide, Johannes, to get further comments from the other side. He said, through the medium:

This is an arrangement prepared beforehand from our side. The person who took this (Mrs Deane) must have been very easy to use. I see this mass of material has poured from her. It is as if smoke or steam were blown out of an engine. This material has made the atmosphere sufficiently clear to take the impress of the prepared mould which you see here. It is not as it would be if the actual faces had pressed in on the medium’s mind. A number of faces were wanted for this photograph, so a mould was prepared. The arrangement is unnatural and does not represent a crowd pressing through to the camera because it has all been carefully prepared beforehand.[xviii]

Seventy years after the heyday of Spiritualism, the belief in spirit photography is now only maintained by a few of the most wilfully credulous. While the general belief in the presence of ghostly experiences has not substantially diminished since the 1920s,[xix] the faith in photography as a foolproof way for positively recording them is now only found scattered at the outer limits of paranormal enthusiasm, or in the furthest reaches of the World Wide Web. The Spiritualist religion, once a mass-scale social movement, has given way to a plethora of New Age spiritualities. Plenty of earnest psychic investigators still exist, but they have shrunk in eminence and shifted their attention to other supposedly paranormal phenomena, such as ESP. And the great celebrity mediums of the past, who conducted their séances before batteries of scientists, have been succeeded by either franchised telephone psychics or tabloid TV entertainers.

But during the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries Spiritualism implanted its powerful visions and mysterious characters deeply into popular consciousness. Even non-believers couldn’t help but be fascinated. And this legacy of ideas and images is still very much with us. Spiritualism’s phantasmagoric images haunted our entertainment media right from the start. Spiritualist thaumaturges shared many of their surreptitious techniques — phosphorescence, ventriloquism, and sleight-of-hand — with the impresarios of eighteenth-century magic-lantern shows or a nineteenth-century stage-magic acts. Within a few years of the invention of cinema trick films such as G. A. Smith’s Photographing a Ghost, 1898, or Georges Melies’ The Spiritualist Photographer, 1903, were openly displaying in the film theatre the same special effects of double exposure and superimposition as the spirit photographers were cunningly deploying in the séance. The films were explicitly tricks, and generally poked fun at Spiritualism, but they too relied on evoking, within the conventions of entertainment, a parallel sense of wonder at the uncanny visual world the new technology of the cinema was opening up.[xx]

Later, in the 1920s, Hollywood responded to the post-war craze for Spiritualism by making many films featuring Spiritualistic phenomena, which were represented as being either fake or real depending on the plot of the film. For example Darkened Rooms, 1929, starred a fake spirit photographer who is tricked by his kind-hearted girlfriend, posing as a spirit, into renouncing his dubious profession; while Earthbound, 1920, featured the apparition of a murdered man, earthbound by his allegiance to the worn out credo of no God and no afterlife, being finally able to release himself by appearing to his wife and making amends for his sins. Films such as this, even though they used special effects to recreate spiritualistic phenomena, received the warm approbation of Spiritualists. One Spiritualist, Dr Guy Bogart, even visited the set of another film with a pro-Spiritualistic theme, The Bishop of the Ozarks, which featured a séance and mental telepathy, and was convinced he saw a real spirit manifest itself on the set to complement the film’s special effects.[xxi]

The Spiritualists were modernists, they understood the phenomena they witnessed, and believed in, to be part of the same unfolding story of progress as science and technology. Even if they failed in their expectation that they would be the heralds of a new dawn of expanded awareness, the imaginative world they created for themselves still provides compelling ideas and powerful images for the present. In the last decade or so, the relatively dormant ideas and images of Spiritualism have undergone a resurgence in contemporary culture. The plots of many contemporary horror films are twisting again on the spectral convergence of the ghost and the photographic image that spirit photography has always shared with cinema.[xxii] The enigmatic figure of the spirit photographer is making occasional appearances in novels.[xxiii] Various contemporary video and installation artists are using new technologies to create spectral effects borrowed from the history of Spiritualism. In their art works these phantasmagoric images of disembodied entities are cast adrift into a technologically occulted ‘beyond’. Like the Spiritualists before them the artists imagine this as an electromagnetic world sundered from our own, yet still connected to it by the various media technologies, new and old.[xxiv] Historians of cinema, photography and visual culture have begun to pay attention to spirit photography and to treat it as an important part of the experience of modernity.[xxv] And finally the idea of ‘haunting’ — where unquiet ‘ghosts’ from the historical past return to the present to challenge us to redeem them — is being increasingly invoked in contemporary philosophy and cultural studies. It even has its own name: hauntology. [xxvi]

There is no doubt that the Spiritualists were extremely credulous. But credulity is a relative term, most often used by those with social or intellectual authority to dismiss those who have none. The Spiritualists’ legacy can still be felt today because they used their credulity actively and creatively. Most people buffeted by the incredible wars, deaths, losses and changes of the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries kept their insistent thoughts and desires safely internalised as psychological fantasy, private reverie, or familiar ritual. But the Spiritualists externalised them — they collectively dramatized them in their séances, or projected them into new and uncanny technologies such as telegraphy, the wireless, or photography.

The Spiritualists’ sense of themselves as pioneers of a new age meant that they were able to take large ideas and use them for their own ends. They took the idea of the afterlife, present in the Judeo-Christian tradition for thousands of years, and domesticated it, bringing it down to the scale of the parlour. They took the idea of the photograph, which had been touted for decades as a personal mnemonic machine able to capture and fix shadows, and enlarged it to fill the universe. In the end, spirit photography turned out to not be a scientific truth, or a religious miracle. But, for its historical time, it remains an extraordinary act of collective imagination. Together, gullible clients, cunning mediums, opportunistic mentors and hubristic investigators created a rich imaginative economy where ideas, images and interpretations circulated, cross infected and interpenetrated each other.

Photography remained the central tool in the psychic investigator’s arsenal for so long because it promised mechanical objectivity. In 1891 the scientist and Spiritualist Alfred Russel Wallace challenged the SPR to properly investigate spirit photographs because they were ‘evidence that goes to the very root of the whole inquiry and affords the most complete and crucial test in the problem of the subjectivity or objectivity of apparitions.’[xxvii] But what ensnared those who looked to photographic evidence as a forensic test was that photographs had the same problem of subjectivity and objectivity as apparitions. The faces they documented changed, depending on who was looking at them. Eleanor Sidgwick, the SPR’s most clear headed thinker, pointed out: ‘It must be remembered that if one frequently sees a portrait of an absent person, one’s recollection is of the portrait, not really of the original, so that once a person has clearly made up his mind as to the likeness, his recollection of the original would adapt itself.’[xxviii]

When a client chose to believe that the dead lived and were struggling to transmit news of their continued existence back from the other side; and when, in the mysterious alchemical cave of the darkroom, that client saw before their very eyes a face emerge to join their own face on a photographic plate; and when they decided, perhaps even after some initial trepidation, to let themselves be flooded with the absolute conviction that they recognised that face as a lost loved one; then a certain photographic truth was revealed. Not a forensic truth, but an affective truth. That incontrovertible truth remains as relevant today as it ever was. Photographs are never just simple images of reality, they are also ideas and interpretations. The portrait photograph is not just made by the bald technical operation of snapping someone in front of the camera, it is also constituted by the context of the ‘performance’ of the portrait, and by the way the resultant image is incorporated into people’s lives after it is made.

Despite all the subsequent technological changes of the late twentieth and early twenty-first centuries, despite the complete digitization and computerization of the photographic process, in looking back to spirit photography’s overheated milieu and intense images, we can still our own attitudes to, and uses of, the portrait photograph written large — very large. For us, as for those that made the decision to visit spirit photographers, by looking into a photograph we believe that we can see and feel the presence of someone sundered from us by death, or by time itself.

‘Different Viewpoints!’ Harbinger of Light, October (1919),

‘Mysterious ‘Spirit’ Photograph’, Sunday Pictorial, 13 July 1919,

‘Conan Doyle in Australia’, Light, December 18 (1920),

‘Sir Arthur Conan Doyle at Carnegie Hall’, Harbinger of Light, July (1923),

U. Baer, Spectral evidence : photography and trauma, (Cambridge, Mass.: MIT Press, 2002)

F. Barlow, ‘Psychic Photography. Perfect Proof’, Light, 20 August

F. Barlow, ‘Does Psychic Photography Prove Survival’, Light, 28 October (1922),

R. Brandon, The Spiritualists : The Passion for the Occult in the Nineteenth and Twentieth Centuries, (London: Weidenfeld And Nicolson, 1983)

J. Coates, Photographing the Invisible: Practical studies in Spirit Photography, Spirit Portraiture, and other Rare but Allied Phenomena, (London: L.N. Fowler & Co, 1911)

Society for Psychical Research, Cambridge University Library, M. Connell, Letter to SPR, 4 March, 1925, Deane Medium File

J. Derrida, Specters of Marx : the state of the debt, the work of mourning, and the New international, (New York: Routledge, 1994)

A. C. Doyle, The wanderings of a spiritualist, (London,: Hodder and Stoughton, 1921)

A. C. Doyle, The Case for Spirit Photography, (London: Hutchinson and Co, 1922)

A. Ferris, ‘The Disembodied Spirit’, in The Disembodied Spirit, ed. by A. Ferris (Brunswick, Maine: Bowdoin College, 2003)

N. Fodor, Encyclopedia of Psychic Science, (London: Arthurs Press Limited, 1933)

A. F. Gordon, Ghostly matters: Haunting and the Sociological Imagination, (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1997)

T. Gunning, ‘Phantom Images and Modern Manifestations: Spirit Photography, Magic Theatre, Trick Films, and Photography’s Uncanny’, in Fugitive Images: From Photography to Video, ed. by P. Petro (Bollomington: Indiana University Press, 1995)

T. Gunning, ‘Haunting Images: Ghosts, Photography and the Modern Body’, in The Disembodied Spirit, ed. by A. Ferris (Brunswick, Maine: Bowdoin College, 2003)

F. Jameson, ‘Marx’s Purloined Letter’, New Left Review, 209, January/February

M. Jolly, ‘Spectres from the Archive’, in Le Mois de la Photo a Montreal, ed. by M. Langford (Montreal: McGill-Queens University, 2005)

G. Jones, Sixty Lights, (London: Random House, 2004)

K. Jones, Conan Doyle and the Spirits: the spiritualist career of Sir Arthur Conan Doyle, Aquarian Press, 1989)

H. Norman, The Haunting of L., (London: Picador, 2003)

J. Oppenheim, The other world : spiritualism and psychical research in England, 1850-1914, (Cambridge Cambridgeshire ; New York, NY: Cambridge University Press, 1985)

A. Owen, The Darkened room : women, power and spiritualism in late nineteenth century England, (London: Virago, 1989)

P. C. Phillips, ‘Close Encounters — Thematic Investigation: Photography and the Paranormal’, Art Journal, 62, (Fall 2003), 3

J. Sconce, Haunted media : electronic presence from telegraphy to television, (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2000)

E. Sidgwick, ‘On Spirit Photographs: A Reply to Mr A. R. Wallace’, Proceedings of the Society for Psychical Research, 1891-1892 (1891-1892),

E. Stead, Faces of the Living Dead, (Manchester: Two Worlds Publishing Company, 1925)

J. T. Taylor, ”Spirit Photography’ with remarks on fluorescence’, British Journal of Photography, 17 March (1893),

P. Thurschwell, ‘Refusing to Give Up the Ghost: Some Thoughts on the Afterlife from Spirit Photography to Phantom Films’, in The Disembodied Spirit, ed. by A. Ferris (Brunswick, Maine: Bowdoin College, 2003)

Deane Medium File, SPR Archives, Cambridge University Library, F. W. Warrick, Letter to Eric Dingwall, 25 May 1923, 1923, Deane Medium File

Society for Psychical Research, Cambridge University Library, F. W. Warrick, Letter to Eric Dingwall, 28 January 1924, 1924, Deane Medium File

J. Winter, Sites of memory, sites of mourning: The Great War in European cultural history, (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1995)

R. Wiseman, M. Smith and J. Wisman, ‘Eyewitness testimony and the paranormal’, Skeptical Inquirer, (November /December 1995),

R. Wiseman, C. Watt, P. Stevens, E. Greening and C. O’Keefe, ‘An investigation into alleged ‘hauntings”, British Journal of Psychology, 94, (2003),

[i] See, R. Brandon, The Spiritualists : The Passion for the Occult in the Nineteenth and Twentieth Centuries, (London: Weidenfeld And Nicolson, 1983); J. Oppenheim, The other world : spiritualism and psychical research in England, 1850-1914, (Cambridge Cambridgeshire ; New York, NY: Cambridge University Press, 1985); A. Owen, The Darkened room : women, power and spiritualism in late nineteenth century England, (London: Virago, 1989) and the indispensable N. Fodor, Encyclopedia of Psychic Science, (London: Arthurs Press Limited, 1933).

[ii] J. T. Taylor, ”Spirit Photography’ with remarks on fluorescence’, British Journal of Photography, 17 March (1893), p. 34.

[iii] J. Coates, Photographing the Invisible: Practical studies in Spirit Photography, Spirit Portraiture, and other Rare but Allied Phenomena, (London: L.N. Fowler & Co, 1911)p. 199.

[iv] A. C. Doyle, The wanderings of a spiritualist, (London,: Hodder and Stoughton, 1921), p. 252.

[v] ‘Conan Doyle in Australia’, Light, December 18 (1920),

[vi] ‘Different Viewpoints!’ Harbinger of Light, October (1919),

[vii] ‘Mysterious ‘Spirit’ Photograph’, Sunday Pictorial, 13 July 1919,

[viii] Brandon, , pp228-229.

[ix] F. Barlow, ‘Psychic Photography. Perfect Proof’, Light, 20 August, p. 453.

[x] F. Barlow, ‘Does Psychic Photography Prove Survival’, Light, 28 October (1922),

[xi] A. C. Doyle, The Case for Spirit Photography, (London: Hutchinson and Co, 1922), p.53.

[xii] Deane Medium File, SPR Archives, Cambridge University Library, F. W. Warrick, Letter to Eric Dingwall, 25 May 1923, 1923, Deane Medium File.

[xiii] Society for Psychical Research, Cambridge University Library, F. W. Warrick, Letter to Eric Dingwall, 28 January 1924, 1924, Deane Medium File.

[xiv] K. Jones, Conan Doyle and the Spirits: the spiritualist career of Sir Arthur Conan Doyle, Aquarian Press, 1989), p. 193.

[xv] ‘Sir Arthur Conan Doyle at Carnegie Hall’, Harbinger of Light, July (1923).

[xvi] Fodor, p. 79.

[xvii] Society for Psychical Research, Cambridge University Library, M. Connell, Letter to SPR, 4 March, 1925, Deane Medium File.

[xviii] E. Stead, Faces of the Living Dead, (Manchester: Two Worlds Publishing Company, 1925)p. 59.

[xix] See R. Wiseman, M. Smith and J. Wiseman, ‘Eyewitness testimony and the paranormal’, Skeptical Inquirer, (November /December 1995), ; R. Wiseman, C. Watt, P. Stevens, E. Greening and C. O’Keefe, ‘An investigation into alleged ‘hauntings”, British Journal of Psychology, 94, (2003),

[xx] For more on magic, spirit photography and cinema see T. Gunning, ‘Phantom Images and Modern Manifestations: Spirit Photography, Magic Theatre, Trick Films, and Photography’s Uncanny’, in Fugitive Images: From Photography to Video, ed. by P. Petro (Bollomington: Indiana University Press, 1995).

[xxi] Letter to Dr Prince from Dr Guy Bogart American Society for Psychical Research, File #21, 05028/05028B. See the Americam Film Institute Silent Film Catalog, www.afi.com/members/catalog/silentHome.aspx?s=1. For contemporary ghost films see P. Thurschwell, ‘Refusing to Give Up the Ghost: Some Thoughts on the Afterlife from Spirit Photography to Phantom Films’, in The Disembodied Spirit, ed. by A. Ferris (Brunswick, Maine: Bowdoin College, 2003).

[xxii] For instance The Others, 2001 and The Ring, 2002. See also M. Jolly, ‘Spectres from the Archive’, in Le Mois de la Photo a Montreal, ed. by M. Langford (Montreal: McGill-Queens University, 2005).

[xxiii] H. Norman, The Haunting of L., (London: Picador, 2003); G. Jones, Sixty Lights, (London: Random House, 2004)

[xxiv] For instance the work of Susan Hiller, Tony Oursler, Zoe Beloff and many others. See also A. Ferris, ‘The Disembodied Spirit’, in The Disembodied Spirit, ed. by A. Ferris (Brunswick, Maine: Bowdoin College, 2003).

[xxv] J. Winter, Sites of memory, sites of mourning: The Great War in European cultural history, (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1995); T. Gunning, ‘Haunting Images: Ghosts, Photography and the Modern Body’, in The Disembodied Spirit, ed. by A. Ferris (Brunswick, Maine: Bowdoin College, 2003); P. C. Phillips, ‘Close Encounters — Thematic Investigation: Photography and the Paranormal’, Art Journal, 62, (Fall 2003), 3; J. Sconce, Haunted media : electronic presence from telegraphy to television, (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2000).

[xxvi] J. Derrida, Specters of Marx : the state of the debt, the work of mourning, and the New international, (New York: Routledge, 1994); A. F. Gordon, Ghostly matters: Haunting and the Sociological Imagination, (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1997); F. Jameson, ‘Marx’s Purloined Letter’, New Left Review, 209, January/February; U. Baer, Spectral evidence : photography and trauma, (Cambridge, Mass.: MIT Press, 2002).

[xxvii] Quoted in E. Sidgwick, ‘On Spirit Photographs: A Reply to Mr A. R. Wallace’, Proceedings of the Society for Psychical Research, 1891-1892 (1891-1892), p. 268.

[xxviii] p. 282.