Of course every photograph is in some sense a document of something else. The very essence of the photography is its ability to make pictorial ‘documents’ of events, be they an abstracted photogram of glass objects arranged and exposed in a darkroom, or an image of a car running a red light recorded by an automatic traffic camera. Nonetheless, the word ‘documentary’ has become used to describe a very particular photographic practice within the medium, or perhaps more accurately, a very particular ethos subscribed to by some photographers. The word has become used not so much to describe a discrete photographic style, or even a particular historical movement, but a complex set of almost moral attitudes to the medium passionately adhered to by some photographers. To the documentary photographer the camera is a tool with which they can personally witness, and perhaps even change, the world.

During the American Civil War (1861-65) the photographer Matthew Brady hired a corps of other photographers to cover all of the major battles for him from their photographic vans, feeding a hungry market in the cities with over 8000 stereo views and cartes-de-visite, which were available for sale from his New York studio. Some were also hand-cut into wood engravings for illustrated magazines. Although the vast majority of the photographs were relatively mundane, the battle views, which because of long exposure times had to be taken after the event, quickly became the most famous. Even though some photographers re-arranged the corpse-strewn battlefields, dragging the corpses into more dramatic compositions and even getting assistants to pose as additional corpses, the visceral connection such photographs forged between the war and the viewer at home was overwhelming. In 1862 the New York Times commented: ‘If [Mr Brady] has not brought bodies and laid them in our door-yards and along the streets, he has done something very like it. […] These pictures have a terrible distinctness. By the aid of a magnifying-glass the very features of the slain may be distinguished.’ [1]

Towards the end of the 1800s the New York police reporter turned social reformer Jacob Riis began to use the flare of magnesium flash powder to penetrate the obscurity of the slums of the Lower East Side. Riis’s flash photographs captured his dishevelled subjects in raw oblivion to the camera’s presence. As the New York Sun reported the ‘night pictures were faithful and characteristic, being mostly snapshots and surprises. In the daytime [the photographers] could not always avoid having their object known, and struggle as they might against it, they could not altogether prevent the natural instinct of fixing up for a picture from being followed’[2] Riis showed his pictures as lantern slides with accompanying commentary, and published them, not as hand cut wood engravings, but as direct half-tone reproductions, in the seminal book How the Other Half Lives, 1890. As a result of his campaigning significant changes were made to the laws surrounding New York’s tenements.

The National Child Labour Committee also recognised the persuasive power of the photograph. Between 1908 and 1918 they hired the sociologist Lewis Hine to travel around the US taking photographs of child labourers in mines and factories. He used deliberate camera angles and framing to emphasise the small stature and pathetic isolation of the child workers, and recorded their names, ages, origins and circumstances. The resulting images, such as Dinnertime. Family of Mrs A. J. Young, Tifton G.A. 1909; Raymond Bykes, Western Union, Norfolk, Va. 1911 and Norman Hall, 210 Park Street, G.A. 1913, were published in the social reform magazine Survey, and used for lantern slide lectures and posters. In the posters the photographs were often laid out graphically to visually tell a story. In ‘Making Human Junk’ for instance, the ‘good material’ of healthy children is processed by a factory into the ‘junk’ of child labourers. To Hine the photograph was a ‘symbol that brings one immediately into close touch with reality […] it tells a story packed into the most condensed and vital form. […] it is more effective than the reality would have been because, in the picture, the non-essential and conflicting interests have been eliminated.’[3]

By the 1920s that the word ‘documentary’ was being used to describe this new genre of photography. In 1926 the British influential film theorist John Grierson coined the most commonly used definition of the word: the ‘creative treatment of actuality’. This phrase somewhat gnomically captured documentary’s double sense of the camera penetrating a raw social reality, supposedly unaffected by the photographer’s presence, while at the same time the photographer’s ‘vision’ selected, interpreted, symbologized and narrativised that reality in order for it to have maximum impact on the viewer.

This ethic reached its full flowering during the Great Depression of the 1930s. In 1935 the US Government under its New Deal policies set up the Farm Security Administration. Its Historical Section conducted a photographic survey of rural deprivation. The economist Roy Stryker hired a group of photographers, including Dorothea Lange and Walker Evans, to travel across the continent, particularly in the poor South, and send back exposed film to him in Washington to be developed, edited, captioned and distributed to newspapers and magazines. By the end of its life the FSA had assembled an archive of 180 000 images.

Dorothea Lange had previously produced documentary photographs of depression poverty such as White angel breadline, San Francisco of 1932, which with its dynamic composition dramatically compressed the human tension in the scene. For the FSA she produced another image with a similarly compacted triangular composition — Migrant Mother 1936. It was reproduced immediately in the San Francisco News, leading to food being sent to the pea pickers camp where it had been taken, and was hung in the Museum of Modern Art in 1941, which led to it becoming a national icon of madonna-like forbearance in the face of suffering.

Walker Evans shot his subjects frontally with a large-format camera, describing, as in Untitled (street scene Southern city) c1936, the solidity of surfaces and forms in objective, rectilinear detail. In 1938 he exhibited his FSA photographs at the Museum of Modern Art and published them in the monograph American Photographs, where for the first, rather than being reproduced amongst columns of text in magazines and newspapers, they were reproduced as art in a careful sequence, one image at a time, and with minimal captioning. The introduction to the book described Evans’s work as ‘straight’ photography — ‘there has been no need for Evans to dramatize his material with photographic tricks, because the material is already, in itself, intensely dramatic. Even the inanimate things, bureau drawers, pots, tires, bricks, signs, seem waiting in their own patient dignity, posing for their picture.’[4]

In 1936 Evans had lived for a time in the shack of an Alabama sharecropper family. On assignment from Fortune magazine, he and the writer James Agee probed into the minutia of the their downtrodden lives as they shared their private space. When Evans’s fine-grained images of the dry, scrubbed surfaces of the house and the lined, weathered faces of the family were reproduced, together with Agee’s extended lyrical text, in the book Let Us Now Praise Famous Men, 1941, they served to not only dignify, but almost ennoble the family’s stoical poverty.

Many FSA-style photographs were reproduced in Life magazine, the most famous picture magazine of the period. Commencing publication in 1936, Life used new high-speed presses, coated paper-stock, and quick-drying inks to cheaply reproduce photographs in both quality and quantity. Featuring easy to digest ‘picture stories’ — photographs with short captions spread across several pages — Life reached a circulation of six million by 1960, before the alternative entertainment of television began erode it sales figures.

Life’s optimistic patriotism and belief in American values fed directly into a massive exhibition of 503 giant photographic enlargements selected from 273 photographers by the famous photographer and curator Edward Steichen. Called The Family Of Man, it was exhibited as a spectacular installation at the Museum of Modern Art in 1955, and then toured the world in several versions as a form of Cold War propaganda, even reaching Moscow in 1959. It saw the human race as one big ‘family’, modelled on the supposed ideal the American nuclear family, and celebrated birth, love, marriage, and death as eternal humanist values. The exhibition was massively popular, but was not without its critics. When it reached Paris in 1956 the cultural theorist Roland Barthes excoriated it for cloaking continuing social inequalities across the world with supposed ‘universal’ values: ‘Whether or not the child is born with ease or difficulty, whether or not his birth causes suffering to his mother, whether or not he is threatened by a high mortality rate, whether or not such and such a type of future is open to him: this is what your Exhibitions should be telling people, instead of the eternal lyricism of birth. The same goes for death: must we really celebrate its essence once more, and thus risk forgetting that there is still so much we can do to fight it?’[5]

The advent of smaller cameras such as the Leica, designed around cinematographic film and introduced in 1925, had allowed photographer to work in more difficult and different places. Picture agencies, such as Berlin’s Dephot agency founded in 1928, or New York’s Black star Agency founded in 1936, began to supply photographs from their networks of photographers to the new, cheap, mass circulation, flick-through, picture magazines such as Berliner Illustrirte Zeitung (begun 1884), Britain’s Picture Post (begun 1938) and Paris’s Vu (begun 1928), who used skilled graphic designers to lay them out in visually exciting collages of image and text.

In 1936 Vu sent the Dephot agency photographer Robert Capa to cover the Spanish Civil War, where he photographed a falling republican soldier. When the photograph was republished by Life the following year it was captioned: ‘Robert Capa’s camera catches a Spanish soldier the instant he is dropped by a bullet through the head in front of Cordoba.’[6] Although recent scholarship has convincingly suggested that this famous photograph was staged, it is still a touchstone for twentieth century photo-journalism because it gave the viewer a strong sense of the intrepid bravery of the photographer risking his own life so the viewer could be vicariously immersed in the unfolding event itself.[7]

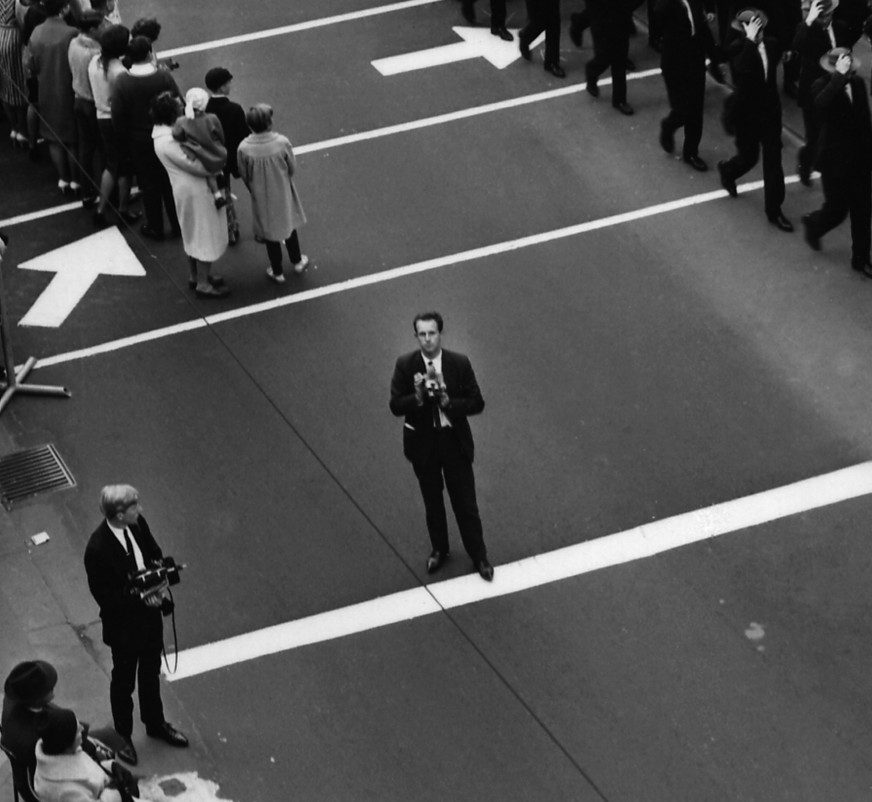

Henri Cartier-Bresson switched to the Leica in 1932 and began a caree photographing around the world selling his images through picture agencies. He photographed nimbly, moving quickly and unnoticed through events, seeking the instant where the three dimensions of the event, and the two dimensions of the photograph, would cohere into what he called the ‘decisive moment’. In his 1952 book The Decisive Moment he wrote: ‘In photography there is a new kind of plasticity, [a] product of the instantaneous lines made by movements of the subject. […] But inside movement there is one moment at which the elements in motion are in balance. Photography must seize upon this moment and hold immobile the equilibrium of it.’[8] This famous philosophy, which is evident in various degrees in all of his photographs, including At the Opera 1950s, became a shorthand way to describe the visual power of the attuned photographer to apparently encapsulate an entire event in a single image.

In 1947 Cartier-Bresson, Capa, and other photographers, founded the photo agency Magnum, which became the most prestigious and famous face of the documentary ethos. In the 1950s Ernst Haas (Egyptian boys, 1955); Elliot Erwitt (New York City, 1953 and Moscow, 1959); and Willy Ronis (Le vigneron girondin, 1945), were members. Recent members have included Sebastiao Salgado and the art photographer Martin Parr. Salgado works on global projects with big humanitarian themes, such as his book Workers of 1993. Although grittily ‘real’, his photographs are also highly stylised, with compositions echoing old master paintings and endowed with a heightened sense of universal significance by dramatic high-contrast printing. Parr, on the other hand, who also works in book form, celebrated the cheap pleasure of the British working classes in bilious colour and with cruel irony in such books as The Last Resort, 1986.

As other forms of mass entertainment began to compete with the picture magazines, documentary photographers relied more and more on the art book and the gallery exhibition as a venue for their work. Weegee blasted New York’s late-night streets with a flash-gun and press camera to produce images such as Tramp 1940. But his shocking high-contrast crime scenes only became true pulp-opera when they were assembled into the inkily-black book New York, Naked City in 1945. In 1955 Robert Frank received a Guggenheim Fellowship to travel through America on a Beat-style road trip. Taking 28,000 photographs with his Leica, he sequenced 83 of them into the book The Americans, published in 1959. Although Frank was inspired by Evans’s American Photographs, his book subscribed to neither the desiccated nobility of the FSA, nor the cosy humanism of the Family of Man, rather it discovered isolated and lonely Americans caught within a worn-out, grainy America, which was in the process of fracturing into subcultures.

In the subsequent decades American photographers such as Lee Friedlander, Garry Winogrand and William Eggleston incessantly worked the sidewalks with their 35mm cameras, cramming the jumble of the street into their photographic frames. They edited the hundreds of thousands of photographs they took into thematic books and exhibitions with little or no text. An exception to this model of the street photographer was Diane Arbus, perhaps the most famous of the post war American documentary photographers, who was still working for magazines such as Harpers Bazaar when she was selected, along with Friedlander and Winnogrand, for the Museum of Modern Art’s seminal New Documents exhibition of 1967. Her portraits of eccentric, marginalised, vulnerable people undergoing ‘slow-motion private smashups’, to use Susan Sontag’s words, gained in universal power as they were removed from the narrative context of the picture stories for which they were taken, and exhibited in isolation on the gallery wall.[9]

Although it is now considerably more threadbare than in its glory days of the 1930s the genre of documentary photography still survives. The advent of digital photography has not changed the fundamentally ‘documentary’ nature of the photograph— we all still habitually believe that a photograph represents actuality. We are all still curious about ‘how the other half lives’, be they the desperately poor, the obscenely rich, or the distantly exotic. The decisive moment of the photograph retains its power to stop us in our tracks and momentarily mesmerise us, in a way a video grab still can’t.

Perhaps the aspect of documentary to have suffered the most damage is the idea of intrepid documentary photographers heroically seeking after the truth. Now they have to share space in the public’s imagination with less savoury types of photographers, such as sleazy paparazzi. In addition many of their icons have been revealed to be as theatrically staged as the rest of photography’s genres, and their motivations and effectiveness have also come into question. Once their photographs are out in the public domain can they protect their meanings from being hijacked by the many different contexts in which they are used, and the different captions they are given? Are they not just feeding our desire for short-term spectacle, our need to visually consume a momentary ‘hit’ of pity or disgust before we turn the page?

Photographers have responded to these questions in a variety of ways. For instance Larry Clark in Tulsa, 1971 or Nan Goldin in The Ballad of Sexual Dependency, 1986 abandoned any sense of sociological objectivity or creative distance as they photographed from within their own lives, documenting the subcultures they were members of, and desperate events they actively took part in. Other photographers such as Laura Mulvey in The Bowery in two inadequate descriptive systems, 1975 attempted to reveal the ‘constructed’ nature of photographic truth by treating their photographs not as self-sufficient and self-explanatory chunks of reality, but by embedding them in laborious structures of textual qualification which declared that photography too was just another language system. The Chilean photographer Alfredo Jaar photographed in Rwanda just after the massacres of 1994. He wanted to bear witness to the genocide, but refused to flood the world with yet more disposable images of horror and despair. Instead, in the work Real Pictures, 1995, he built funereal monuments out of 372 sealed black boxes, each one containing one of his colour photographs of the massacres, with a textual description of the unseen image on the top of the box. Recently the ‘other half’, once the mere passive subjects of the documentary photographer’s compassionate camera, have now become image-makers themselves. Examples include Britain’s Black Audio Film Collective set up by black photographers and filmmakers in Hackney in London in 1982 in the aftermath of inner-city protests against racism

Perhaps the enduring thing documentary photography has bequeathed to us is not so much the familiar historical icons it has produced over its history, but its vast repositories of millions of unknown images which are now collected in picture libraries and data banks around the world. Many of them, like the Corbis archive, founded by Bill Gates in 1989, are now online and instantly accessible. But even these mega documentary archives, which have consumed older picture libraries, photo agency and newspaper collections, are being rivalled by the smaller quirky personal collections and the diverse vernacular archives which are constantly being unearthed. Perhaps these personal snapshots and anonymous record photographs, which were taken not in order to advance a social cause or express a creative vision, will ultimately be just as valuable to us as those taken under the banner of the word ‘documentary’.

[1] Quoted in Michel Frizot. A new history of photography, Kèonemann, Kèoln 1998, p144

[2] ‘Flashes from the Slums: Pictures Taken in Dark Places by the Lightning Process, Some of the Results of a Journey through the City with an Instantaneous Camera —the Poor the Idle and the Vicious’, New York Sun, February 12, 1888, reprinted in Beaumont Newhall. Photography : essays & images : illustrated readings in the history of photography, Secker & Warburg, London 1981, p156)

[3] Lewis Hine, ‘Social Photography: How the Camera May Help in Social Uplift’, quoted in Alan Trachtenberg. Reading American photographs : images as history, Mathew Brady to Walker Evans, Hill and Wang, New York, NY 1989, p207

[4] Walker Evans and Lincoln Kirstein. American photographs, The Museum of Modern Art, New York, N.Y 1988 np

[5] Roland Barthes, Mythologies, Paladin Grafton, London 1973, p102

[6] Life, 12 July 1937, p19

[7] Alex Kershaw. Blood and champagne : the life and times of Robert Capa, Macmillan, London 2002; Caroline Brothers. War and photography : a cultural history, Routledge, London ; New York 1997

[8] Henri Cartier-Bresson, ‘The Decisive Moment’, in Vicki Goldberg. Photography in print : writings from 1816 to the present, Simon and Schuster, New York 1981, p385

[9] Susan Sontag. On photography, Penguin Books, Harmondsworth 1979, p36