When I was thinking about what to say tonight I thought I would start with the distinctive aspect of this exhibition — how stylistically and historically diverse the photographs are. The curator has had the entire collection of the NGV to dive into at will to extract and re-combine photographs under her broad overarching theme of narrative fiction. She’s able to do this virtuoso piece of orchestration with a fair amount of confidence that because of the nature of the medium the images, although diverse, will kind of hang together in their new semantic configuration because they all, ultimately, have some grounding in reality. For the purposes of tonight, let’s call the NGV collection an archive, although it’s a very particular kind of archive having been carefully curated, selected and vetted to suit the purposes of an art museum.

Of course archives are absolutely fundamental to photography. I think it was Rosalind Krauss who, in the 1980s, said that the central artefact to photography wasn’t the camera but the filing cabinet. (If she was writing today she might add a third artefact, the scanner) The logic of the archive drives the work of creative photographers. We often remind me of bureaucrats, giving ourselves assignments to produce what we like to call ‘bodies of work’ — twelve identical photographs of this, 24 identical photographs of that — which we administer into an archive hung in a row along the wall or stored in a solander box. The public coming to contemporary photography exhibitions becomes like an archivist, comparing the different iterations of the same image, and finding pleasure in contrasting the individualities of each photograph to the generalities and commonalities running through the whole series, which were laid down by the photographer’s initial archival ‘self-assignment’.

Archives also follow the same fundamental law of photography as the individual photograph, that is that the older it is the more interesting it is. Even the most banal photographs taken for the most prosaic purposes become mysterious and evocative when there origins get lost in time. Photographers and curators have used this capacity to construct their own new archives. For instance Thomas Walther, the well-known international collector of avant-garde photography, also assembled a collection of anonymous vernacular photographs from flea markets, these snaps formally look like avant-garde photographs but they have the added dimension of the absence of the photographer’s original motivation, which the viewer can now fill with their own speculation. This collection, now re-authorised by the authority of the connoisseur’s eye, was exhibited as Other Pictures at the MCA in 2002. We might think of Patrick Pound’s installation The Memory Room at the CCP in 2002 as another example of an artist using the mystery of the cast adrift photograph.

But this effect of the evocative mystery of the historically dislocated photograph is exponentially increased when an entire archive is cast adrift across time. In an archive the original motivation to lay down the images in an ordered form is obviously stronger and more defined than the ephemeral evanescent impulse to simply click a shutter, so the archive becomes more mysterious when, through the passage of time, we lose touch with that original motivation. For instance the photographer Rozalind Drummond found an archive of WW11 photographs in an East Berlin junk shop. The lost family connections between the photographs, and the silenced exchange of affiliative looks between the images, amplifies the power of the whole archive beyond any of the single photographs. Like virtually photographer I know Rozalind brought this collection because she thought it was important, it had to be rescues. But now she doesn’t quite know what to do with it. Everything we as artists can think of to do to these archives eventually just seems to be somehow redundant.

Archives also allow photographs to have access to another dimension which is usually denied to the individual photograph — the monumental. A single image which is blown up to monumental size is very often just that — over blown. The decisive moment still retains it’s temporal contingency, its urgency, no matter what scale it is. It never seems to be able to get out of the flow of history. But if an archive of individual moments is spatialized into a grid, photography can become monumentalised. For instance in her recent Adelaide Biennale anti-war protest piece Not in My Name, Silvia Velez downloaded thousands of images from the internet of the futile protests around the world against the inevitable George Bush invasion of Iraq. After abstracting them and printing them on Post-it notes, the most ephemeral of ‘reminders’, she monumentalised them on a wall, mimicking the inscriptions of martyr’s names on so many marble monuments.

The classic essays on the archive in photography is Alan Sekula’s “Reading an Archive” from 1983. In that he refers to an archive as a ‘clearing house of meaning’. Photographs are made available to be separated from the specificity of their original use when they are deposited in an archive. When they are plucked from an archive and re-used and re-contextualised they are given different meanings. This is how historians, book editors and curators use archives. A semantics is given to the archival images which they didn’t have when they lay dormant and ordered in their original grid. This is what Kate has done in curating this show, out of the dormant taxonomy of the art-historical archive — the artist’s name, or their period (19th century views, 1990s art photograph, etc) — a new semantic enunciation is made: narrative fictions.

For a long time, as well as historians and curators, artists have been fascinated by archives and have used them as ‘clearing houses of meaning’. In Europe one immediately thinks of Gerhard Richter or Christian Boltanski, where specific archives get re-configured as intimations of mortality and the ineluctable processes of time and history. Closer to home, artists like Elizabeth Gertsakis have for a long time been re-narrativising archives, both personal and public, to make statements, amongst other things, about identity.

But without wanting to make too big a deal out of it, I think there has been a slight turn recently in this re-use of archives. I think that not only has there has been a general increase in interest in archives from artists. And I think that there has been turn away from seeing the archive as a clearing house of meaning, a resource from which new enunciations can be made, towards wantinh keeping the archive’s mysterious integrity intact, as discreet and ineffable.

Some people might have gone to Ross Gibson’s performance of Life after Wartime at ACMI Sunday before last. This piece concerns itself with an archive of post war Sydney police images Ross has been working on for six years. I’m not sure what he did in Melbourne, but in the performance I saw at the Sydney Opera House he and his collaborator Kate Richards sat at midi-keyboards at laptops. But instead of being connected to audio samples the keys were connected to strings of images. The images they brought from the archive were combined with haikus by Ross, and this was accompanied by a live soundtrack by the Necks, who are known for their ominous soundtracks to movies such as The Boys. The texts and images generate open-ended non-specific narratives around a couple of characters and locations in a ‘port city’.

Now this idea of ‘playing’ the archive as if it was some giant pipe-organ might not seem to be too different from a curator who plays the tune of ‘narrative fiction’ on the pipe organ of the NGV collection. But there was an element of automation in the way the ‘story engine’ generates the loose narrative, and certainly Ross is keen on preserving the integrity, the artefactuality of the original archive.

Whenever I work with historical fragments, I try to develop an aesthetic response appropriate to the form and mood of the source material. This is one way to know what the evidence is trying to tell the future. I must not impose some pre-determined genre on these fragments. I need to remember that the evidence was created by people and systems of reality independent of myself. The archive holds knowledge in excess of my own predispositions. This is why I was attracted to the material in the first instance — because it appeared peculiar, had secrets to divulge and promised to take me somewhere past my own limitations. Stepping off from this intuition, I have to trust that the archive has occulted in it a logic, a coherent pattern which can be ghosted up from its disparate details so that I can gain a new, systematic understanding of the culture that has left behind such spooky detritus. In this respect I am looking to be a medium for the archive. I want to ‘séance up’ the spirit of the evidence….” ‘Negative Truth: A new approach to photographic storytelling’, Photofile 58, December 1999

One could argue that, contrary to his claim, Ross has imposed “some pre-determined genre” on the fragments, that of the psychological detective story. But nonetheless, in seeking to be a voodoo spiritualist ‘medium’ for the archive Ross is trying to make contact with it as a whole.That is the distinction I want to make here. Artists are beginning to work with archives on their own terms rather than to make their own enunciations from them.

(As an aside, it is interesting to compare this work with the two opening ACMI exhibitions Ross curated, Remembrance and the Moving Image. These exhibitions, you will remember, were filled with slowed down, granular, archival film footage. But, as always, the forward thrust of film footage, even when turned against itself into an entropic downward spiral, still doesn’t approach the mute enigma, and the feeling of narrative potential, which the still archival image gives.)

Another example of this turn to a concern with communing with the personality of an archive as a whole is a recent series by the Sydney photographer Anne Ferran who shows in Melbourne at Sutton. The series 1-38 comprises 38 images which are details from each of 38 photographs which were taken of female psychiatric patients in 1948. Looking at Ferran’s earlier work we can see why she would be fascinated by this archive, everything about it is lost, the name of the original photographer, the purpose of the photographs, the names of the women, and their disease. The fragments, which are of the hands and torso of the women, are impassively displayed in a strip around the wall. So the structure, personality or mood of the original archive is preserved. Her cropping simply amplifies the inchoate choreography of distress which the inmates exhibited.

The greatest archive we have is our own negative-files. Sometimes the processes of history can turn a few sheets of negatives into an acute and self-contained archive with it’s own ‘mood, logic or occult spirit’, to use Ross Gibson’s words. The Canberra photographer Denise Ferris lived in South Africa for a short while in 1979 and 1980, because of a doomed love affair. Whilst there, she photographed in a poor part of Cape Town called District Six. District Six was bulldozed just before the end of Apartheid. All the remains now is a museum, and the fading memories of those who used to live there. Asked to return to South Africa recently for an exhibition, Denise looked at her District Six negatives for the first time in almost a quarter of a century. Left high and dry by the onward current of her own life, each negative seemed as important as the other. As in Anne Ferran’s work, 1-38, what basis did she have to discriminate between them? She printed them all up onto thin sheets of paper and hung them like falling leaves in two ovoid shapes. The shapes were repeated by the thin strips of prints she made from her original notes on the edge of the negative sheets. People from District Six welcomed the exhibition enthusiastically, and the museum will collect a set. But the archive remains as remote from Denise as ever, she met none of her original subjects while she was there.

Peter Robertson’s two recent exhibitions, Sharpies and Beyond Xanadu also record this uncanny process of what was at one point simply a personal collection becoming, through a process of return and re-nomination, an historical archive. By simply reprinting and renominating some of the photographs in his own photo albums, as well as the photo albums of his friends, under the rubric ‘Sharpies’, or by exhibiting his fashion model tear-sheets and model tests, he alloys together different authorities and moods in the archive: autobiography, nostalgia and urban anthropolgy.

A similar example comes from Brenda L Croft. In the series Man About Town she simply reproduced every Kodachrome slide in the yellow box she found amongst her father’s possessions after he died. Croft did not insert herself into the photographs, she did not make them into ‘art’. It allows them to maintain their ineffable distance from us in the present. There is plenty of space left for us to fantasise and speculate about his life in the 1950s when he was a young single man, before he met the artist’s mother, before he knew that he had a twin sister, and before he found his mother from whom he had been taken as a baby.

I’ve been interested in archives for virtually all my career. Recently I’ve also been interested in spirit photographs (not taking them, but researching them). I was amongst the collection of the Society for Psychical Research in the Cambridge University Library researching the 1920s spirit photographer Ada Deane when three large albums came up with 3000 spirit photographs. I had the same reaction I think many people have when they come across a lost archive: I’ve just got to get this out. What to do. I guess I steered a course between the two tendencies I have tried to identify this evening. I wanted to preserve the archive’s integrity, to ‘séance up’ it’s heart and soul, but I also wanted to make art. So I homed in on details of expression and body language.

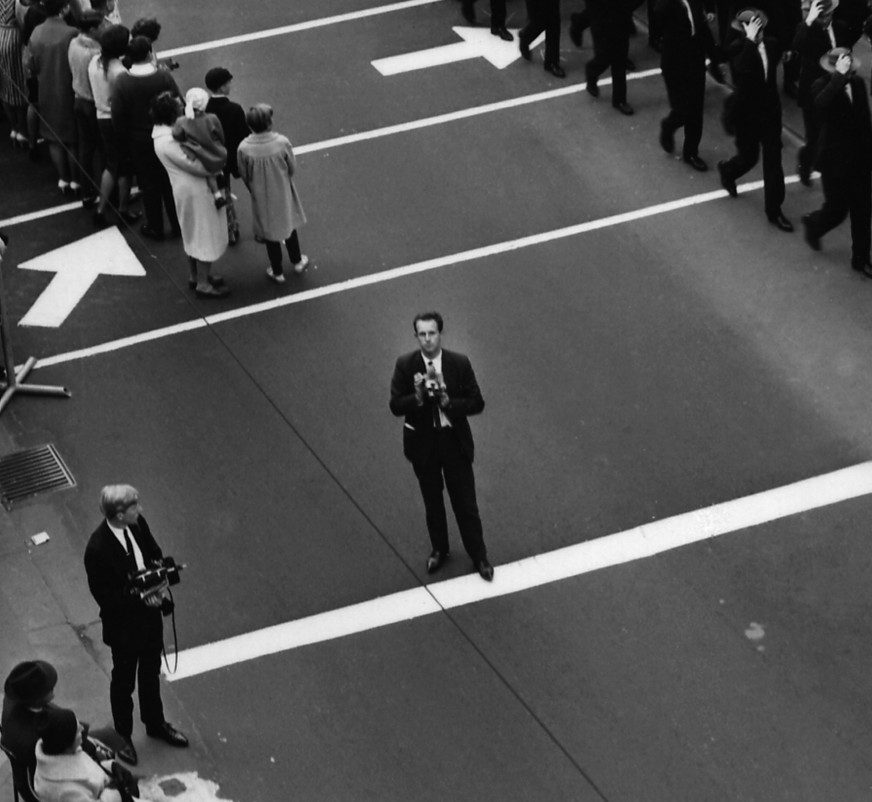

In a previous body of work, Nineteen Sixty-Three: News and Information, 1997, I used a flatbed scanner to digitally excoriate the original image to produce a high resolution computer file, which was then cropped, enlarged, enhanced and printed. Working in the Australian Archives I made my way through 3000 propaganda photographs taken by the Australian News and Information Bureau during 1963. The metaphor I had in my mind was an excavation of the original mise en scene for photographic details to be isolated like archaeological artefacts. In both cases I gravitated not towards the main subject of the image, but towards its background or its incidental detail. I avoided faces and the centripetal force of the eyes, and instead drifted towards body language—the tensing of muscles or wricking of limbs; and the wearing of clothes—the gaping of lapels, hitching of cuffs and rucking of crotches. I was also interested in textures and material surfaces, as well as the re-vectorisation of the photograph’s original spatial composition that re-cropping allowed.