Spectres from the Archive

The dead have been making themselves visible to the living for millennia. In Purgatory, Dante asked Virgil how it was that he was able to see the souls of the dead with whom he was speaking, while their bodies had been left behind in the grave. Virgil beckoned a spirit who replied that, just as the colours of reflected rays filled rain-filled air, so the un-resurrected soul virtually impressed its form upon the air.[1] Similarly, the ghost of Hamlet’s father was as invulnerable to blows from a weapon as the air. It was a mere image which faded at cock-crow. But, for the last several centuries, these diaphanous, insubstantial condensations of light and air have been acquiring a technological, rather than a natural, phenomenology.

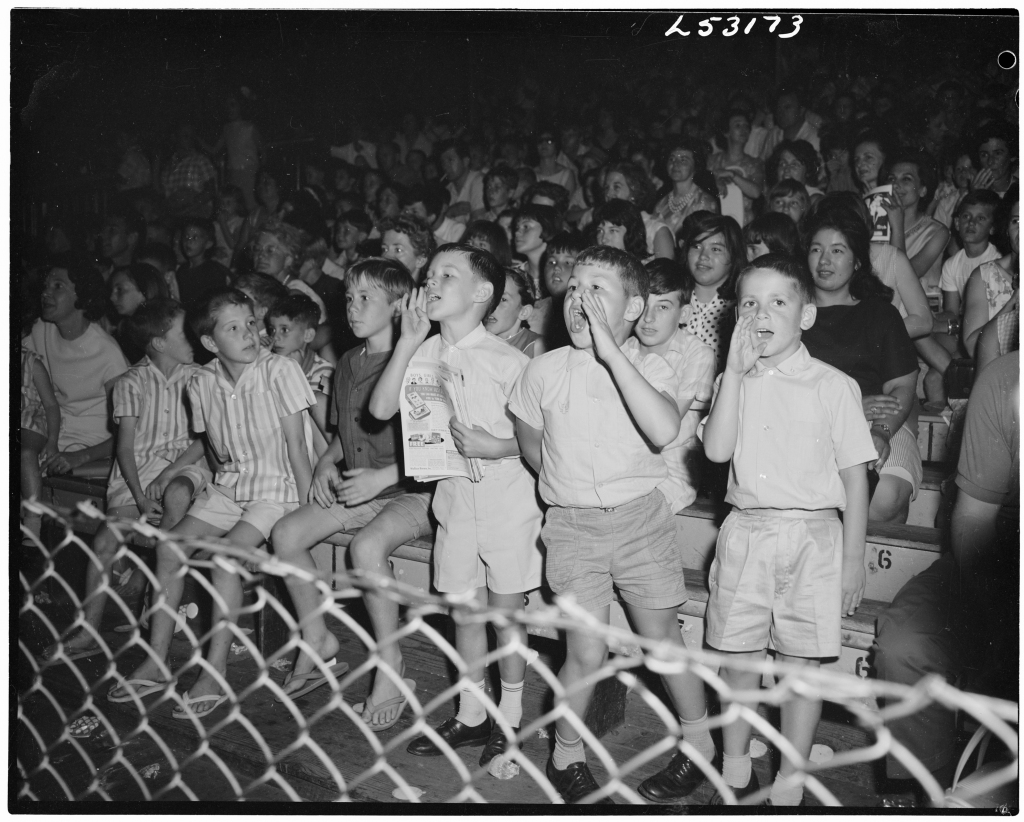

In the years following the French Revolution Etienne-Gaspard Robertson terrified crowds with the first phantasmagoria show, which he staged in a convent that had been abandoned by its nuns during The Terror. He made his magic-lantern projections, of paintings of gory figures such as The Bleeding Nun, appear to be phantasmic entities by blacking out their glass backgrounds and projecting them onto stretched gauzes, waxed screens, and billows of smoke. By placing the magic-lantern on wheels, which was dollied backwards by an operator, he gave these luminous, translucent apparitions the power to suddenly loom out over the audience. At an 1825 London phantasmagoria show the impact of this effect on the audience was electric. According to an eyewitness the hysterical screams of a few ladies in the first seats of the pit induced a cry of ‘lights’ from their immediate friends, but the operator made the phantom, The Red Woman of Berlin, appear to dash forward again. The confusion that followed was alarming even to the stoutest: “the indiscriminate rush to the doors was prevented only by the deplorable state of most of the ladies; the stage was scaled by an adventurous few, the Red Woman’s sanctuary violated, the unlucky operator’s cavern of death profaned, and some of his machinery overturned, before light restored order and something like an harmonious understanding with the cause of alarm”.[2]

In the eighteenth century the host of supernatural beings — such as ghosts, devils and angles — who had long inhabited the outside world alongside humans, were finally internalised under the illumination of Reason as mere inner-projections of consciousness — fantasies of the mind or pathologies of the brain. During this period, in Terry Castle’s phrase, “Ghosts and spectres retain their ambiguous grip on the human imagination; they simply migrate into the space of the mind”.[3] But, as she goes on to explain, technologies such as the phantasmagoria allowed these images of consciousness to project themselves outside the mind once more, into the space of shared human experience. They were destined to return from the brain to re-spectralize visual culture.

The eighteenth century also changed the way in which death was experienced. No longer an ever-present communal experience, the effect of someone’s death became focussed onto a few individuals — their family — just as the various processes of death and mourning became privatised and quarantined within the institutions of the home, the hospital, and the necropolis.[4] One response to this was the rise in the nineteenth century of an extraordinary cult of the dead — Spiritualism — which gripped the popular imagination well into the twentieth century. Spiritualism was the belief that the dead lived, and that they could communicate. Spiritualism was a quintessentially modernist phenomenon, and Spiritualists, as well as the spirits themselves, used all emerging technologies to demonstrate the truth of survival.[5]

The early years of Spiritualist communication were conducted under the metaphoric reign of the telegraph. In 1848 the world’s first modern Spiritualist medium, a young girl called Kate Fox, achieved world-wide fame by developing a simplified morse-code of raps to communicate with the spirits who haunted her small house in upstate New York. Twenty years later portraits of spirits began to appear on the carte-de-visite plates of the world’s first medium photographer, William Mumler. Spirit photographs were a personal phantasmagoria. Just as Robertson’s phantoms were lantern-slides projected onto screens, spirit photographs were actually prepared images double-exposed onto the negative. But the spirit photographer’s clients sat for their portrait filled with the belief that they might once more see the countenance of a loved one; they concentrated on the loved one’s memory during the period of the exposure; and they often joined the photographer in the alchemical cave of the darkroom to see their own face appear on the negative, to be shortly joined by another face welling up from the emulsion — a spirit who they usually recognised as a loved one returning to them from the oblivion of death. For these clients the spirit photograph was not just a spectacle, it was an almost physical experience of the truth of spirit return.

Public interest in spirit photography reached its highest pitch in the period just after World War One, when the unprecedented death toll of the war, combined with the effect of an influenza pandemic, caused a public craze for Spiritualism.[6] On Armistice Day in 1922 the London spirit photographer Mrs Ada Deane stood above the crowd at Whitehall and opened her lens for the entire duration of the Two Minutes Silence. When the plate was developed it showed a ‘river of faces’, an ‘aerial procession of men’, who appeared to float dimly above the crowd.[7]

When the ardent Spiritualist convert, Sir Arthur Conan Doyle, lectured to a packed house at Carnegie Hall the following year, he flashed this image up on the lantern-slide screen. There was a moment of silence and then gasps rose and spread over the audience, and the voices and sobs of women could be heard. A woman in the audience screamed out through the darkness, “Don’t you see them? Don’t you see their faces?” before falling into a trance.[8] The following day the New York Times described the image on the screen: “Over the heads of the crowd in the picture floated countless heads of men with strained grim expressions. Some were faint, some were blurs, some were marked out distinctly on the plate so that they might have been recognised by those who knew them. There was nothing else, just these heads, without even necks or shoulders, and all that could be seen distinctly were the fixed, stern, look of men who might have been killed in battle.”[9]

The Spiritualist understanding of photography was underwritten by a keen, and highly imaginative, conception of two substances: ether and ectoplasm. Since Morse’s first telegraphing of the words “what hath God wrought” in 1844, and Kate Fox’s first telegraphing to the spirits four years later, the air had steadily thickened as it was filled by more and more of the electromagnetic spectrum: from the electrical ionisation of residual gas in a cathode-ray tube (discovered by Sir William Crookes, who also photographed the full body materialization of a spirit Katie King by electric light); to x-rays (developed in part by Sir Oliver Lodge, who communicated with his dead son, Raymond, for many years after he fell in World War One); to radio-waves; to television transmission. From the late nineteenth century until the period when Einstein’s theories made it redundant, most physicists agreed that some intangible interstitial substance, which they called ether, must be necessary as the medium to carry and support X-rays, radio waves, and perhaps even telepathic waves, from the point of transmission to point of reception. Since sounds, messages and images could be sent through thin air and solid objects, why not portraits from the other side?[10]

If ether allowed Spiritualist beliefs to be made manifest through electrical science, ectoplasm allowed them to be made manifest through the body. For about thirty years after the turn of the century various, mainly female, mediums extruded this mysterious, mucoid, placental substance from their bodily orifices, whilst groaning as though they were giving birth. Sometimes this all-purpose, proto-plasmic, inter-dimensional stuff seemed able to grow itself into the embryonic forms of spiritual beings, at other times it acted as a membranous emulsion which took their two dimensional photographic imprint. For instance on 1 May 1932 a psychic investigator from Winnipeg, Dr T. G. Hamilton, photographed a teleplasmic image of the spirit of Doyle (who had ‘crossed over’ the year before) impressed into the ectoplasm that came from mouth and nostrils of a medium.[11]

Just as spirit photographs were in reality various forms of double exposure, such teleplasms were in reality small photographs and muslin swallowed by the medium and then regurgitated in the darkness to be briefly caught by the investigator’s flash during the intense psychodrama of the séance. Nonetheless, for the Spiritualists they confirmed an associative chain that poetically and technically extended all the way from ectoplasm to photographic emulsion — creamy, hyper-sensitive to light, and bathed in chemicals.[12]

The Spiritualists placed photography at the centre of their cult of the dead. And modernity’s cultural theorists placed death at the centre of their response to photography. Photography was compared to embalming, resurrection, and spectralization. The horrible, uncanny image of the corpse, with its mute intimation of our own mortality, haunted every photograph. For instance to Siegfried Kracauer, writing in the 1920s, a photograph was good at preserving the image of the external cast-off remnants of people, such as their clothes, but could not capture their real being. The photograph: “dissolves into the sum of its details, like a corpse, yet stands tall as if full of life.”[13] The blind production and consumption of thousands upon thousands of these photographs was the emergent mass-media’s attempt to substitute itself for the acceptance of death implicit in personal, organic memory: “What the photographs by their sheer accumulation attempt to banish is the recollection of death, which is part and parcel of every memory image. In the illustrated magazines the world has become a photographable present, and the photographed present has been entirely eternalised.”[14]

To a subsequent critic, Andre Bazin, our embrace of the photograph was also a pathetic attempt to beat death. The sepia phantoms in old family albums were, “no longer traditional family portraits, but rather the disturbing presence of lives halted at a set moment in their duration … by the power of an impassive mechanical process: for photography does not create eternity, as art does, it embalms time, rescuing it simply from its proper corruption.”[15]

In Roland Barthes’ Camera Lucida, his almost necrophilic meditation on photography written while in the grim grip of grief for his mother, the photograph’s indexicality, the fact that it was a direct imprint from the real, made it a phenomenological tautology, where both sign and referent, “are glued together, limb by limb, like the condemned man and the corpse in certain tortures.”[16] In posing for a portrait photograph, he says, “I am neither subject nor object but a subject who feels he is becoming an object: I then experience a micro-version of death … : I am truly becoming a spectre.”[17] Later he reduces this essence of the portrait photograph down even further. It is not only an exact process of optical transcription, it is also an exquisitely attenuated chemical transfer, an effluvial emanation of another body—“an ectoplasm of ‘what-has-been’: neither image nor reality, a new being really.”[18]

Although wildly extrapolating upon the intimate connection between photography and death, the Spiritualist use of photography ran counter to the dominant perception of the photograph as irrevocably about pastness, about the instantaneous historicisation and memorialisation of time. Spirit photographs cheerfully included multiple times, and multiple time vectors. Spirit photographs were collected and used by Spiritualists very much like the millions of other personal snapshots that were being kept in albums and cradled in hands. But for them they did not represent the exquisite attenuation of the “that has been” of a moment from the past disappearing further down the time tunnel as it was gazed at in the present, nor the frozen image’s inevitable prediction of our own mortality. Rather, they were material witnesses to the possibility of endless emergences, returns and simultaneities.

The images were performative. They worked best when their sitters had seen them well-up from the depths of the emulsion in the medium’s developing tray, or seen them suddenly flashed on the screen in a lantern-slide lecture. Their power lay not in their reportage of a pro-filmic real elsewhere in time and space, but in their audience’s affective response to them in the audience’s own time and place. They solicited a tacit suspension of disbelief from their audience, at the same time as they brazenly inveigled a tacit belief in special effects. Spirit photographs used the currency of the audience’s thirst for belief to trade-up on the special effects they borrowed from cinema and stage magic —which had also descended from the phantasmagoria. They shamelessly exploited the wounded psychology of their audience to confirm their truth, not by their mute indexical reference to the real, but through the audience’s own indexical enactment of their traumatic affect. Their truth was not an anterior truth, but a manifest truth that was indexed by the audience as they cried out at the shock of recognition for their departed loved ones.

In mainstream thought about photography the two signal characteristics which defined photography and photography alone, physical indexicality and temporal ambiguity, were in their turn produced by two technical operations: the lens projecting an image of an anterior scene into the camera, and the blade of the shutter slicing that cone of light into instants. But the Spiritualist theory of photography discounted that technical assemblage, along with the ‘decisive moments’ it produced. It shifted the locus of photography back to the stretched sensitive membrane of the photographic emulsion, and dilated the frozen instant of the snapshot over the full duration of the séance.

Many contemporary artists are rediscovering the richly imaginative world the Spiritualists created for themselves. Others are strategically deploying the same technical effects once surreptitiously used by spirit photographers. These contemporary invocations are no longer directly underpinned by Spiritualist faith, but they do reinhabit and reinvent the metaphysical, performative and iconographic legacy of the Spiritualists. For these artists, as much as for the Spiritualists themselves, images, bodies, beliefs and memories swirl around and collide in intoxicating obsession. And technologies of image storage, retrieval, transmission and reproduction are simultaneously the imaginative tropes, and the technical means, for communicating with the beyond. For the Spiritualists the beyond was a parallel ‘other side’ to our mundane existence, for some contemporary artists it is quite simply the past.[19]

For instance the New York based artist Zoe Beloff folds famous episodes from the history of Spiritualism back into her use of new interactive technologies. Examples are the interactive CD-Rom, Beyond, 1997; the stereoscopic film based on the extraordinary ‘auto-mythology’ of the nineteenth-century medium Madame D’Esperance, Shadowland or Light From the Other Side, 2000; and the installation of stereoscopic projections based on the first séances of Spiritualism’s most famous ectoplasmic medium, Ideoplastic Materializations of Eva C., 2004. Some of Beloff’s works resurrect dead-end technologies and apparatuses, such as a 1950s stereoscopic home-movie camera to, for instance, directly link contemporary notions of virtuality to nineteenth century stage illusions, such as ‘Pepper’s Ghost’, where a live performer behind a sheet of glass interacted with a virtual phantasm reflected in it. She deploys the occult to re-introduce desire, wonder, fear and belief into what most media histories would have us think was just the bland march of ever-increasing technological sophistication. Like many of us, and like all of the people to first see a photograph or hear a sound recording, Beloff is still fascinated by the fact that the dead live on, re-embodied in technology. She remains interested in conjuring them up and interfacing between past and present like a Spiritualist medium.[20]

For his installation The Influence Machine, 2000, the New York video artist Tony Oursler projected giant ghost-heads of the pioneer ‘mediums’ of the ether, such as Robertson, John Logie Baird and Kate Fox, onto trees and billows of smoke in the heart of the world’s two biggest media districts, London’s Soho Square and New York’s Madison Square Park. These disembodied heads uttered disjointed phrases of dislocation and fragmentation, while elsewhere a fist banged out raps, and ghostly texts ticker-taped up tree trunks. In his Timestream, an extended timeline of the development of ‘mimetic technologies’, Oursler drew an occult trajectory through the more conventional history of media ‘development’, and identified that the dead no longer reside on an inaccessible ‘other side’, but survive in media repositories. To him: “Television archives store millions of images of the dead, which wait to be broadcast … to the living … at this point, the dead come back to life to have an influence … on the living Television is, then, truly the spirit world of our age. It preserves images of the dead which then continue to haunt us.”[21]

The most famous spectre of the nineteenth century was the spectre of communism which, in the very first phrase of the Communist Manifesto, Marx declared to be haunting Europe. But this, unlike almost every other spectre, was not a grim revenant returning from the past, but a bright harbinger of the future when capitalism would inevitably collapse under its internal contradictions ushering in the golden age of communism. But now communism is dead and buried, and when its spectre is raised it is not to haunt us, but to be a parable affirming the supposed ‘naturalness’ of capitalism.[22]

This circular irony formed the background to Stan Douglas’s installation Suspiria from Documenta 11 of 2003. The spectral temper of the imagery was achieved by overlapping a video signal with the over-saturated Technicolor palette of the 1977 cult horror film Suspiria. The piece deconstructed Grimm’s 250 fairy tales into a data-base of narrative elements, often centring on characters vainly seeking short cuts to wealth and happiness by extracting payments and debts. These fragments were videoed using actors wearing clothes and make-up in the primary colours. The chromatic channel of the video signal was separated and randomly superimposed, like an early-model colour TV with ghosting reception, over a switching series of live surveillance video-feeds from a stony subterranean labyrinth. These fleeting evanescent apparitions endlessly chased each other round and round the blank corridors.[23]

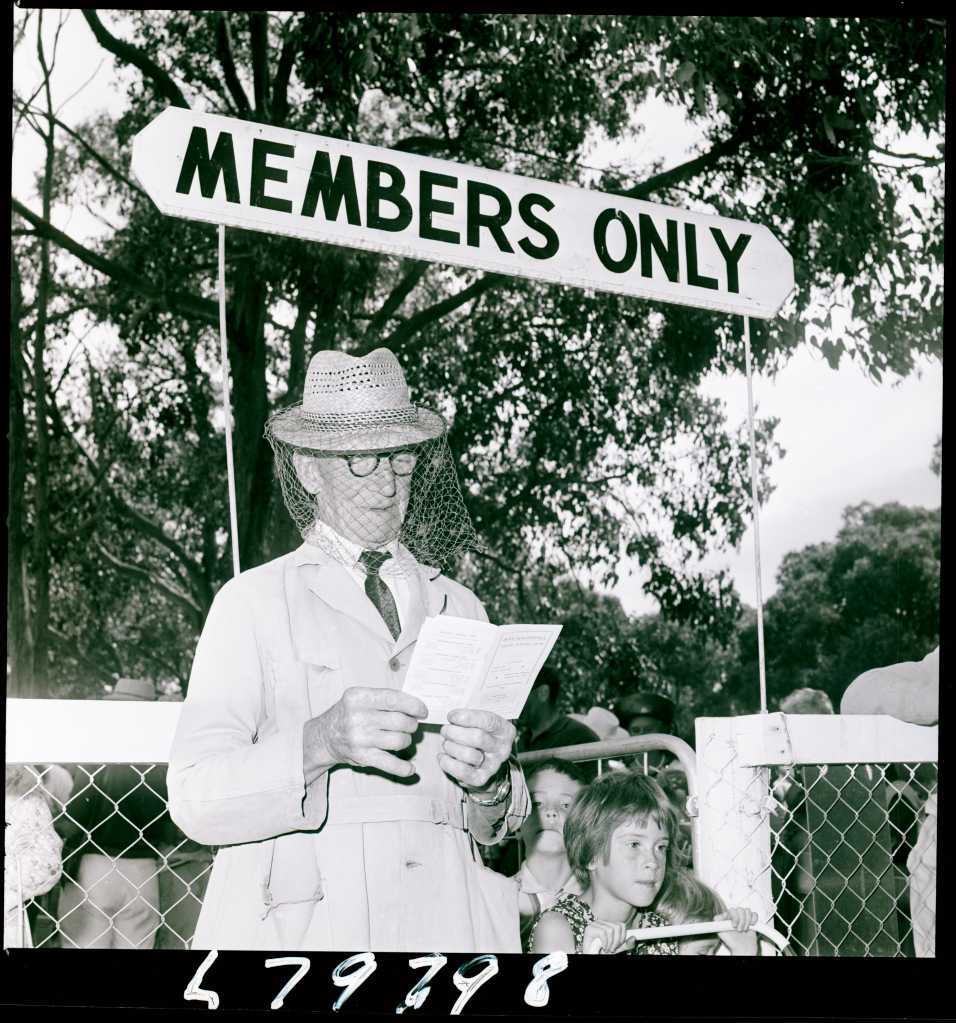

As well as the phantasmagoric apparatuses of projection and superimposition, with their long histories in mainstream entertainment as well as the occult, artists such as Douglas or Oursler have begun to deploy another newly occulted apparatus — the data-base. For instance, Life after Wartime, presented at the Sydney Opera House in 2003, was an interactive, ‘performance’ of an archive of crime scene photographs which had been assembled by Sydney’s police-force in the decades following the Second World War. Kate Richards and Ross Gibson sat at laptops and midi keyboards and brought up strings of images which, combined with evocative haikus, were projected onto two large screens. Beneath the screens The Necks, a jazz trio well known for their ominous movie music, improvised a live soundtrack of brooding ambience. Although not directly picturing spectres, the texts and images did generate open-ended non-specific narratives around a set of semi-fictionalised characters and locations in the ‘port city’ of Sydney. These characters became invisible presences occupying the creepy emptiness of the crime scenes. The element of automation in the way the story engine generated the loose narratives preserved the integrity, the artefactuality, of the original archive. Ross Gibson wrote:

Whenever I work with historical fragments, I try to develop an aesthetic response appropriate to the form and mood of the source material. This is one way to know what the evidence is trying to tell the future. I must not impose some pre-determined genre on these fragments. I need to remember that the evidence was created by people and systems of reality independent of myself. The archive holds knowledge in excess of my own predispositions. This is why I was attracted to the material in the first instance — because it appeared peculiar, had secrets to divulge and promised to take me somewhere past my own limitations. Stepping off from this intuition, I have to trust that the archive has occulted in it a logic, a coherent pattern which can be ghosted up from its disparate details so that I can gain a new, systematic understanding of the culture that has left behind such spooky detritus. In this respect I am looking to be a medium for the archive. I want to ‘séance up’ the spirit of the evidence … [24]

In seeking to be a voodoo spiritualist ‘medium’ for the archive, the work was not trying to quote from it, or mine it for retro tidbits ripe for appropriation, so much as to make contact with it as an autonomous netherworld of images. This sense of the autonomy of other times preserved in the archive also informs the work of the Sydney photographer Anne Ferran. In 1997 she made a ‘metaphorical x-ray’ of a nineteenth-century historic house. She carefully removed items of the colonial family’s clothing from its drawers and cupboards and, in a darkened room, laid them gently onto photographic paper before exposing it to light. In the photograms the luminous baby dresses and night-gowns floated ethereally against numinous blackness. To Ferran the photogram process made them look, “three-dimensional, life-like, as if it has breathed air into them in the shape of a body. … With no context to secure these images, it’s left up to an audience to deal with visual effects that seem to have arisen of their own accord, that are visually striking but in an odd, hermetic way.”[25]

In contrast to this diaphanous ineffability, Rafael Goldchain’s Familial Ground, 2001, was an autobiographical installation in which the artist physically entered the archive of the family album, seeking to know and apprehend the dead. He re-enacted family photographs of his ancestors, building on his initial genetic resemblance to them by using theatrical make-up, costuming, and digital alteration, weaving the replicated codes of portraiture through their shared DNA. He saw these performances, along with the uncannily doubled portraits they produced, as acts of mourning, remembrance, inheritance and legacy for his Eastern European Jewish heritage, which had been sundered by the Holocaust. The portraits supplemented public acts of Holocaust mourning with a private genealogical communion with the spectres of his ancestors who still inhabited his family’s albums. The dead became a foundation for his identity, which he could pass on to his son. They took on his visage as they emerged into visibility, reminding him of the unavoidable and necessary work of inheritance.[26]

The Native American artist Carl Beam also builds his contemporary identity on the basis of a special connection he feels to old photographs. He uses liquid photo-emulsion, photocopy transfer and collage to layer together historic photographs — such as romanticised portraits of Sitting Bull — and personal photographs —such as family snaps — into ghostly palimpsests. The collages directly call on spectres from the past to authorise his personal, bricolaged spiritual symbology. They allow him to time travel and re-build a foundation for his identity out of fragments from the past.

In 1980 Australia’s most eminent art historian Bernard Smith gave a series of lectures under the title The Spectre of Truganini. In the nineteenth century Truganini had become a much-photographed colonial celebrity as the ‘last’ of the ‘full-blood’ Tasmanian Aborigines. Smith’s argument was that, despite white Australia’s attempt to blot out and forget the history of its own brutal displacement of Australia’s indigenous population, the repressed would continue to return and haunt contemporary Australia until proper amends were made.[27]

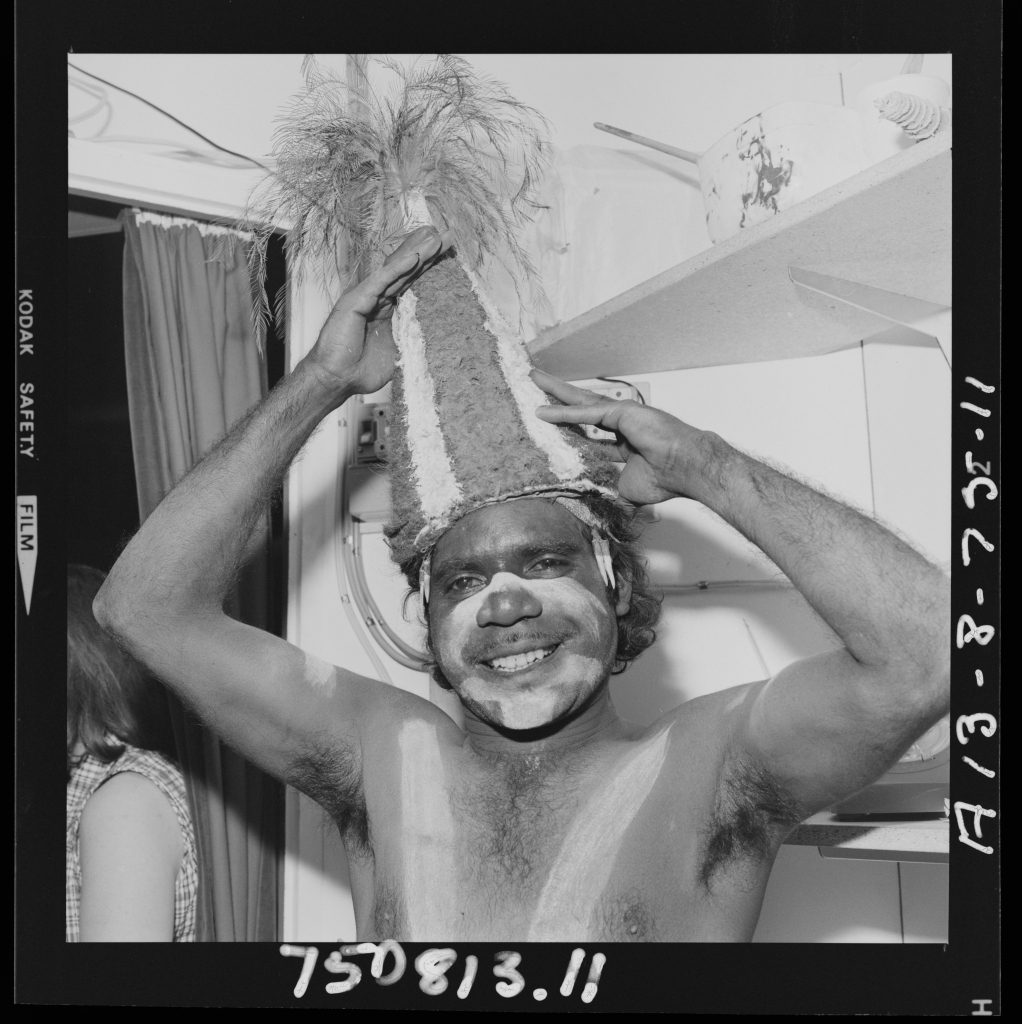

As indigenous activism grew in intensity and sophistication during the 1980s and 1990s, anthropological portraits, such as those of Truganini, began to be conceived of as not only the theoretical paradigm for colonial attempts at genocide, but also as acts of violence in themselves, technically akin to, and instrumentally part of, that very process of attempted genocide. They began to be used by young indigenous artists to ‘occult up’ their ancestors. Their re-use attempted to capture a feeling of active dialogue with the past, a two way corridor through time, or a sense of New Age channelling.

The anthropological photographs used by urban indigenous photographers are not monuments, like the statues or photographs of white pioneers might aspire to be, because they do not commemorate a historical closure on the past. In a way they are anti-monuments, images of unquiet ghosts who refuse to rest in their graves. In a Barthesian meditation on nineteenth-century anthropological photographs the indigenous photographer Brenda L. Croft, who uses Photoshop to float imprecatory words of loss within images of her ancestors, retroactively invested the agency of political resistance in the portraits. “Images like these have haunted me since I was a small child and … [and] were instrumental in guiding me to use the tools of photography in my work. … The haunted faces of our ancestors challenge and remind us to commemorate them and acknowledge their existence, to help lay them, finally, to rest.”[28]

However, rather than laying their ancestors to rest, some indigenous artists have photographically raised them from the dead to enrol them in various campaigns of resistance. For instance one of the first Australian indigenous photographers to receive international attention was Leah King-Smith. Her exhibition Patterns of Connection, 1992, travelled throughout Australia as well as internationally. For her large deeply-coloured photo-compositions anthropological photographs were copied and liberated from the archives of the State Library of Victoria to be superimposed as spectral presences on top of hand-coloured landscapes. This process allowed Aboriginal people to flow back into their land, into a virtual space reclaimed for them by the photographer. In the words of the exhibition’s catalogue: “From the flaring of velvety colours and forms, translucent ghosts appear within a numinous world.”[29]

Writers at the time commented on the way her photographs seemed to remobilise their subjects. The original portraits ‘contained’ their subjects as objects, which could be held in the hand, collected, stored and viewed at will. Their placement of the figure well back from the picture plane within a fabricated environment created a visual gulf between viewer and object. But King-Smith reversed that order. Her large colour-saturated images ‘impressed’ the viewer: “The figures are brought right to the picture plane, seemingly extending beyond the frame and checking our gaze with theirs”.[30]

Leah King-Smith comes closest to holding spiritualist beliefs of her own. She concluded her artist’s statement by asking that, “people activate their inner sight to view Aboriginal people.”[31] Her work animistically gave the museum photographs she re-used a spiritualist function. Many of her fellow indigenous artists criticised her for being too generalist, for not knowing the stories of the people whose photographs she used, and not asking the permission of the traditional owners of the land she makes them haunt. But the critic Anne Marsh described this as a “strategic essentialism”. “There is little doubt, in my mind, that Leah King-Smith is a kind of New Age evangelist and many serious critics will dismiss her work on these grounds. … But I am interested in why the images are so popular and how they tap into a kind of cultural imaginary [in order] to conjure the ineffable. … Leah King-Smith’s figures resonate with a constructed aura: [they are] given an enhanced ethereal quality through the use of mirrors and projections. The ‘mirror with a memory’ comes alive as these ancestral ghosts … seem to drift through the landscape as a seamless version of nineteenth century spirit photography.”[32]

While not buying into such direct visual spirituality, other indigenous artists have also attempted to use the power of the old photograph make the contemporary viewer the subject of a defiant, politically updated gaze returned from the past. In a series of works from the late 1990s Brook Andrew invested his nineteenth century subjects, copied from various state archives, with a libidinous body image inscribed within the terms of contemporary queer masculinity, and emblazoned them with defiant Barbara Krugeresque slogans such as Sexy and Dangerous, 1996, I Split Your Gaze, 1997 and Ngajuu Ngaay Nginduugirr [I See You], 1998.

Andrew uses the auratic power of the original Aboriginal subjects to simply re-project the historically objectifying gaze straight back to the present, to be immediately re-inscribed in a contemporary politico-sexual discourse. However other strategic re-occupations of the archive show more respect for the dead, and seek only to still the frenetic shuttle of appropriative gazes between us and them. For instance in Fiona Foley’s re-enactments of the colonial photographs of her Badtjala ancestors, Native Blood, 1994, the gaze is stopped dead in its tracks by Foley’s own obdurate, physical body. To the post-colonial theorist Olu Oguibe: “In Foley’s photographs the Other makes herself available, exposes herself, invites our gaze if only to re-enact the original gaze, the original violence perpetrated on her. She does not disrupt this gaze nor does she return it. She recognises that it is impossible to return the invasive gaze … Instead Foley forces the gaze to blink, exposes it to itself.”[33]

But the ghosts of murdered and displaced Aborigines aren’t the only spectres to haunt Australia. White Australia also has a strong thread of spectral imagery running through its public memory for the ANZAC digger soldiers, who fell and were buried in their thousands in foreign graves during all of the twentieth century’s major wars. Following World War One an official cult of the memory developed around the absent bodies of the dead, involving painting, photography, elaborate annual dawn rituals, and a statue erected in each and every town.

Like indigenous ghosts, Anzac ghosts also solicit the fickle memory of a too self-absorbed, too quickly forgetful later generation. Since 1999 the photographer Darren Siwes, of indigenous and Dutch heritage, has performed a series of spectral photographs in Australia and the UK. By ghosting himself standing implacably in front of various buildings, he refers to an indigenous haunting, certainly; but because he is ghosted standing to attention whilst wearing a generic suit, he also evokes the feeling of being surveilled by a generalised, accusatory masculinity — exactly the same feeling that a memorial ANZAC statue gives.

Siwes’ photographs are mannered, stiff and visually dull, but they have proved to be extraordinarily popular with curators in Australia and internationally. One reason for his widespread success may be that the spectre he creates is entirely generic — a truculent black man in a suit — and therefore open to any number of guilt-driven associations from the viewer. Similarly, many of the other indigenous artists who have used photographs to haunt the present have produced works which are visually stilted or overwrought. But they too have been widely successful, not because of their inherent visual qualities, but because of the powerful ethical and political question which the very idea of a spectre is still able to supplicate, or exhort, from viewers who themselves are caught-up in a fraught relationship between the present and the past, current government policy and historical dispossession. That question is: what claims do victims from past generations have on us to redeem them?[34]

As photographic archives grow in size, accessibility and malleability they will increasingly become our psychic underworld, from which spectres of the past are conjured. Like Dante’s purgatory they will order virtual images of the dead in layers and levels, waiting to interrogate the living, or to be interrogated by them. Through photography the dead can be invoked to perform as revenants. They will be used to warn, cajole, inveigle, polemicise and seduce. But as always it is we, the living, who will do the work of interpretation, or perform the act of response. Like the viewers of Robertson’s phantasmagoria we think we know that these spectres are mere illusions, the products of mechanical tricks and optical effects. But just as surely we also know that the images we are seeing were once people who actually lived, and that the technologies through which they are appearing to us now will also uncannily project our own substance through time and space in the future, when we ourselves are dead. This knowledge gives photographic spectres more than just rhetorical effect. They can pierce through historical quotation with a sudden temporal and physical presence. Yet at the same time they remain nothing more than the provisional technical animation of flat, docile images. In the end, they are as invulnerable to our attempts to hold onto them as the air.

Martyn Jolly

“Sir Arthur Conan Doyle at Carnegie Hall”, Harbinger of Light, (1923)

P. Ariés, The Hour of Our Death (New York: Alfred A. Knopf 1981)

U. Baer, “Revision, Animation, Rescue”, Spectral Evidence : The Photography of Trauma, (Cambridge, Mass.: MIT Press 2002)

R. Barthes, Camera Lucida (London: Jonathan Cape 1982)

A. Bazin, “The Ontology of the Photographic Image”, What is Cinema, (Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press 1967)

W. Benjamin, “Theses on the Philosophy of History”, Illuminations, (Glasgow: Fontana/Glasgow 1973)

E. Cadava, Words of Light: Theses on the Photography of History (Princeton: Princeton University Press 1997)

T. Castle, “Phantasmagoria and the Metaphorics of Modern Reverie”, The Female Thermometer: Eightenth-Century Culture and the Invention of the Uncanny, (Oxford: Oxford University Press 1995)

T. Castle, “The Spectralization of the Other in The Mysteries of Udolpho“, The Female Thermometer: Eightenth-Century Culture and the Invention of the Uncanny, (Oxford: Oxford University Press 1995)

B. L. Croft, “Laying ghosts to rest”, Portraits of Oceania, (Sydney: Art Gallery of New South Wales 1997)

J. Derrida, Specters of Marx : the state of the debt, the work of mourning, and the New international (New York: Routledge 1994)

S. Douglas, “Suspiria”, Documenta 11_Platform 5: Exhibition Catalogue, 2002)

A. Ferran, “Longer Than Life”, Australian and New Zealand Journal of Art, 1, 1, (2000)

A. Ferris, “Diembodied Spirits: Spirit Photgraphy and Rachel Whiteread’s Ghost“, Art Journal, 62, 3, (2003)

A. Ferris, “The Disembodied Spirit”, The Disembodied Spirit, (Brunswick, Maine: Bowdoin College 2003)

K. Gelder and J. M.Jacobs, Uncanny Australia: Sacredness and Identity in a Postcolonial Nation Melbourne University Press 1998)

R. Gibson, “Negative Truth: A new approach to photographic storytelling”, Photofile, 58, (1999)

T. Gunning, “Phantom Images and Modern Manifestations: Spirit Photography, Magic Theatre, Trick Films, and Photography’s Uncanny”, Fugitive Images: From Photography to Video, (Bloomington: Indiana University Press 1995)

T. Gunning, “Haunting Images: Ghosts, Photography and the Modern Body”, The Disembodied Spirit, (Brunswick, Maine: Bowdoin College 2003)

T. G. Hamilton, Intention and Survival (Toronto: MacMillan 1942)

F. Jameson, “Marx’s Purloined Letter”, New Left Review, 209, January/February, (1995)

M. Jolly, Faces of the Living Dead: The Belief in Spirit Photography (London: British Library in press)

K. Jones, Conan Doyle and the Spirits: the spiritualist career of Sir Arthur Conan Doyle Aquarian Press 1989)

L. Kaplan, “Where the Paranoid Meets the Paranormal: Speculations on Spirit Photography”, Art Journal, 62, 3, (2003)

L. King-Smith, “Statement”, Patterns of Connection, (Melbourne: Victorian Centre for Photography 1992)

S. Kracauer, “Photography”, The Mass Ornament: Weimar Essays, (Cambridge: Harvard University Press 1995)

R. Luckhurst, The invention of telepathy, 1870-1901 (Oxford ; New York: Oxford University Press 2002)

A. Marsh, “Leah King-Smith and the Nineteenth Century Archive”, History of Photography, 23, 2, (1999)

O. Oguibe, “Medium and Memory in the Art of Fiona Foley”, Third Text, Winter, (1995-96)

J. Phipps, “Elegy, Meditation and Retribution”, Patterns Of Connection, (Melbourne: Victorian Centre for Photography 1992)

P. Read, Haunted Earth (Sydney: University of New South Wales Press 2003)

L. R. Rinder, Whitney Biennial 2002, (New York: Whitney Museum of American Art 2002)

K. Schoonover, “Ectoplasm, Evanescence, and Photography”, Art Journal, 62, 3, (2003)

J. Sconce, Haunted Media: Electronic Presence from Telegraphy to Television (Durham, NC: Duke University Press 2000)

B. Smith, The Spectre of Truganini: 1980 Boyer Lectures (Sydney: Australian Broadcasting Commission 1980)

M. Warner, “‘Ourself Behind Ourself — Concealed’: Ethereal whispers from the dark side”, Tony Oursler the Influence Machine, (London: Artangel 2001)

M. Warner, ‘Ourself Behind Ourself — Concealed?’: Ethereal whispers from the dark side, Tony Oursler web site 2001)

M. Warner, “Ethereal Body: The Quest for Ectoplasm”, Cabinet, 12 (2003)

M. Wertheim, The Pearly Gates of Cyberspace: A History of Space from Dante to the Internet (Sydney: Doubleday 1999)

C. Williamson, “Leah King-Smith: Patterns of Connection”, Colonial Post Colonial, (Melbourne: Museum of Modern Art at Heide 1996)

J. Winter, Sites of memory, sites of mourning: The Great War in European cultural history (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press 1995)

[1] Purgatory, 25, 11. 94-101, cited in, Marina Warner, ‘Ourself Behind Ourself — Concealed?’: Ethereal whispers from the dark side, np. For a discussion of Dante’s heaven hell and purgatory in relation to cyberspace see, Margaret Wertheim, The Pearly Gates of Cyberspace: A History of Space from Dante to the Internet, 44-75.

[2] Marina Warner, “‘Ourself Behind Ourself — Concealed’: Ethereal whispers from the dark side”, 75. For more on the phantasmagoria see Terry Castle, “Phantasmagoria and the Metaphorics of Modern Reverie”,

[3] Terry Castle, “The Spectralization of the Other in The Mysteries of Udolpho“, 135.

[4] P Ariés, The Hour of Our Death, cited in Castle.

[5] For Spiritualism and photography see, Martyn Jolly, Faces of the Living Dead: The Belief in Spirit Photography, and Tom Gunning, “Phantom Images and Modern Manifestations: Spirit Photography, Magic Theatre, Trick Films, and Photography’s Uncanny”, andTom Gunning, “Haunting Images: Ghosts, Photography and the Modern Body”, ;Louis Kaplan, “Where the Paranoid Meets the Paranormal: Speculations on Spirit Photography”,

[6] For post war memory and Spiritualism see Jay Winter, Sites of memory, sites of mourning: The Great War in European cultural history,

[7] Martyn Jolly, Faces of the Living Dead: The Belief in Spirit Photography,

[8] Kelvin Jones, Conan Doyle and the Spirits: the spiritualist career of Sir Arthur Conan Doyle, 193.

[9] “Sir Arthur Conan Doyle at Carnegie Hall”, np.

[10] For more on the electromagnetic occult see: Roger Luckhurst, The invention of telepathy, 1870-1901, and Jeffrey Sconce, Haunted Media: Electronic Presence from Telegraphy to Television, Artists who have been inspired by the electroacoustic occult include Susan Hiller, Scanner, Mike Kelley, Joyce Hinterding, David Haines, Chris Kubick and Anne Walsh.

[11] T. Glen Hamilton, Intention and Survival, plates 25 & 27.

[12] For more on ectoplasm see, Karl Schoonover, “Ectoplasm, Evanescence, and Photography”, and Marina Warner, “Ethereal Body: The Quest for Ectoplasm”,

[13] Siegfried Kracauer, “Photography”, 55.

[14] Kracauer, 59. For a discussion of Walter Benjamin’s thought on death in relation to photography see Eduardo Cadava, Words of Light: Theses on the Photography of History, 7-13.

[15] André Bazin, “The Ontology of the Photographic Image”, 242.

[16] Roland Barthes, Camera Lucida, 5-6.

[19] For a recent explorations of this connection see, Alison Ferris, “The Disembodied Spirit”, and Alison Ferris, “Diembodied Spirits: Spirit Photgraphy and Rachel Whiteread’s Ghost“,

[21] Marina Warner, “‘Ourself Behind Ourself — Concealed’: Ethereal whispers from the dark side”, 72.

[22] For Marx’s spectralization see Jacques Derrida, Specters of Marx : the state of the debt, the work of mourning, and the New international, and Fredertic Jameson, “Marx’s Purloined Letter”,

[23] Stan Douglas, “Suspiria”, 557.

[24] Ross Gibson, “Negative Truth: A new approach to photographic storytelling”, 30.

[25] Anne Ferran, “Longer Than Life”, 166,167-170.

[27] Bernard Smith, The Spectre of Truganini: 1980 Boyer Lectures, . For subsequent work on Australia’s indigenous haunting see Ken Gelder and Jane M.Jacobs, Uncanny Australia: Sacredness and Identity in a Postcolonial Nation, and Peter Read, Haunted Earth, .

[28] Brenda L. Croft, “Laying ghosts to rest”, 9, 14.

[29] Jennifer Phipps, “Elegy, Meditation and Retribution”, np.

[30] Clare Williamson, “Leah King-Smith: Patterns of Connection”, 46.

[31] Leah King-Smith, “Statement”, np.

[32] Anne Marsh, “Leah King-Smith and the Nineteenth Century Archive”, 117.

[33] Olu Oguibe, “Medium and Memory in the Art of Fiona Foley”, 58-59.

[34] “There is a secret agreement between past generations and the present one. Our coming was expected on earth. Like every generation that preceded us, we have been endowed with a weak Messianic power, a power to which the past has a claim. That claim cannot be settled cheaply.” Walter Benjamin, “Theses on the Philosophy of History”, 256. For an extensive response to this epigram in the context a photographic archive from the Holocaust see Ulrich Baer, “Revision, Animation, Rescue”,