Essay from: Focus: Australian Government Photographers.

National Archives of Australia, 2023. ISBN 978-1-922209-32-0

Can official photography be interesting? This might seem an odd question to ask, since clearly the National Archives of Australia thinks it can be – hence their exhibition Focus: Australian government photographers.

But this exhibition is swimming against the current of most other photography exhibitions these days. It is not about an urgent social or political cause. It is not devoted to the personal ‘vision’ of a particular photographer. It is not a competition, where anyone can have a go. It does not take us to exotic locations (perhaps it does sometimes) or dramatic events (perhaps it does sometimes), and it does not seek to uncover previously hidden truths (although perhaps, in the end, it does reveal some micro-secrets to us).

Instead, these are publicity photographs for the Australian Government, taken in the second half of the last century. Each one had a job to do on behalf of the government’s various departments, such as trade, immigration and foreign affairs. Each was to be used to promote our science and technology, to show off our industry, our infrastructure, our lifestyle. They were to be used to attract potential migrants with visions of a prosperous, youthful nation; to present to potential trading partners evidence of our cities as modern and safe, our countryside as vast and full of resources, our politicians as capable and trustworthy, and so on.

Such photographs are built on order and predictability, even repeatability. As the years progressed the technologies changed: from the large-format four-by-five-inch black and white sheet film used in the 1950s to the medium format film in both black-and-white and colour used from the mid-1960s, to the 35 mm slide film exclusively in colour used from the 1980s. But the content remained consistent: children, soldiers, scientists, mothers, factory workers, shoppers, sports people, wildlife and so on.

Over the decades the photographs grew into an archive that now numbers hundreds of thousands of images. More importantly, this archive was built systematically. Since 1939, when the Department of Information was first set up at the onset of the Second World War, every photographer entered every photograph they took into a logbook, with names, places and titles. Written in pencil or biro beside each entry was its series identification number and individual control symbol, which still track it in the online catalogue today. There is something beautiful about these creased and dog-eared logbooks as they have accumulated over the decades. The bindings change, the ink and handwriting change, but the system remains the same as the photographers’ entries range across Australia and its region. All of this is preserved in the National Archives’ digital catalogue and can be accessed by any user at a click.

The public accessibility of such a large, well-indexed picture archive has meant that it has already been extensively used by historians and researchers. It has already been supplementing our visual memory as a nation. But the original metadata, recorded by the photographers at various levels of detail as they went about their day-to-day jobs, has produced an enormous integrated dataset.

Of course, as a dataset, various algorithmic affordances are now offered. Archive users are now able to sort the hundreds of thousands of images, this way or that way. For example, they could mine the metadata geographically, displaying all the photographs recorded as being taken in a particular town. With AI working inside the image itself – for instance, on the facial coordinates of all the faces captured by the cameras over the decades – users could extract all the happy people, or all the sad people, for example. Individual photographs could be linked together. Users could pull out of the mix a string of people wearing bow ties, say, or those holding up signs. Or, for that matter, all the people wearing bow ties who are holding up signs. This is the potential remapping of the data space that all that patient work by those photographers has enabled. I can’t wait to be able to do that, and more, in the future. Finely honed, automatic algorithmic searches are one way of opening windows into such an enormous, sprawling, relatively homogenous archive.

But this exhibition has taken a different approach. The archive showcased here was built up by a succession of different photographers. Often their names aren’t even recorded in the catalogue, and in some cases their careers are little known. These photographers weren’t working for themselves; they were applying their skills, talents and personal visual styles to doing a job for this or that government department. They were public servants – public servants with cameras, notebooks and darkrooms. But by considering them as individuals and recognising their professional photography skills in their own right, rather than just as a service to the archive, we can take a fresh look at the images they produced, and at Australian photography as a whole.

Even though these photographers worked for the government, this exhibition has given them back their personalities, their skills, their enthusiasms. The research into the individual careers of the photographers takes us far beyond the single role of ‘government photographer’, and into every aspect of the history of Australian photography. Some, such as Neil Murray, started out as ‘street photographers’, taking photographs on spec of people dressed up for a day out shopping or out on the town. Many were migrants, like the Danish Mike Jensen or the British Eric Wadsworth. Others, such as Jim Fitzpatrick, had years of front-line experience for the newsreel organisation Cinesound, the Daily Telegraph and the RAAF, and as a result his photographs jump off the page. Some, such as Eric Wadsworth or Mervyn Bishop, were newspaper photographers. Many came through the photographic retail industry, from Kodak or Harringtons. Still others, such as John Crowther, began with technical training in chemistry and optics, or as darkroom printers, such as Barry Le Lievre.

From these different corners of Australian photography, all got jobs as government photographers. Recently, after a long period of denigration, the idea of ‘public servant’ has begun to be rehabilitated. We now realise we need them. It turns out that outsourcing to supposedly nimble consultants on short-term contracts cannot substitute for the systematic accumulation of collective knowledge and the long-term honing of individual expertise, particularly when activated by a collective sense of both the ‘public’ and ‘service’. Who knew.

Some could give Orwellian connotations to the names of the departments the photographers worked for, such as the Department of Information (1939–50), the Australian News and Information Bureau (1950–73), the Australian Information Service in the Department of Media (1973–87), the Australian Overseas Information Service (1987–94), the International Public Affairs Branch of the Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade (1994–96) and the Trade Publicity Directorate. And yes, in some sense the people captured by the government photographers are turned into propaganda cyphers. The job of these photographers was literally to stage Australia for a presumed audience: potential overseas trading partners, potential migrants, potential departmental clients. So, yes, the people caught by their cameras are in some sense conscripted, probably without model releases or written permission, to ‘play a part’ as happy Australians, whether they are happy or not.

But the skill of the photographer is such that a little bit of the subject’s selves, outside their role within the ‘public’ scenario of the photograph, is set free within the picture as well. And here are to be found the delights of this exhibition. That is one reason why this exhibition is so timely. It is visual argument against the current atomisation of the public space we share into privatised bubbles, or points of view exclusively focused on the individual. Although staged and somewhat stilted, and representing a now outdated Australia, there is something still fresh in this collective representation.

Yet these are publicity photographs. They weren’t taken for the gallery wall; they were taken for the printed page. They were made to be reproduced in departmental reports, in immigration brochures, and in popular picture magazine stories, posters and advertisements. They needed to be pictorially robust, and able to hold their own on pages crowded with text, graphics and other photographs. This explains the compositional ‘tricks’ many of the photographers employed. For instance, John Crowther frequently put a second visual frame within his camera’s frame. He loved to shoot through door and windows so that even the ‘up’ and ‘down’ escalators of Canberra’s Monaro Mall frame the shoppers at the Embassy Fruit Market in 1966.

Embassy Fruit Market at the Monaro Mall, Canberra 1966. Photographer John Crowther. NAA: A1200, L55270

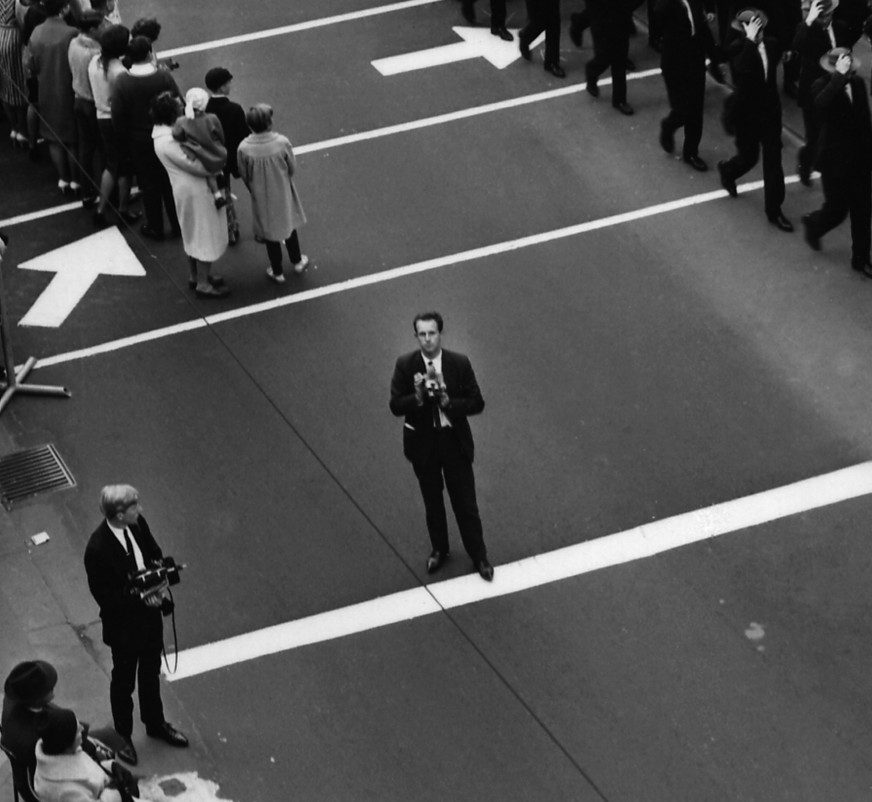

The photographers were also attracted to repeated patterns and visual repetition in their photographs. Sitters are frequently lined up in rows, giving a sense of order and control. The photographers always sought the visual drama in even the most mundane assignment. This show contains several examples of workers being framed within giant concrete pipes, giving a James Bond glamour to the building of Australia’s infrastructure. At other times, the photographers were attracted to the dynamic energy of swirling crowds as in, for instance, Bill Pedersen’s glorious sea of lady’s hats and gloves at the Centenary Melbourne Cup Carnival of 1960, or Jim Fitzpatrick’s 1968 photograph depicting shoppers descending on $5.99 shoes at David Jones in Sydney.

Fashionable spectators don hats and gloves at the Centenary Melbourne Cup Carnival, Melbourne, Victoria 1960. Photographer Bill Pedersen. NAA: A1500, K6328

Shoppers descend on $5.99 shoes at David Jones, Sydney 1968. Photographer Jim Fitzpatrick. NAA: A1200, L77320

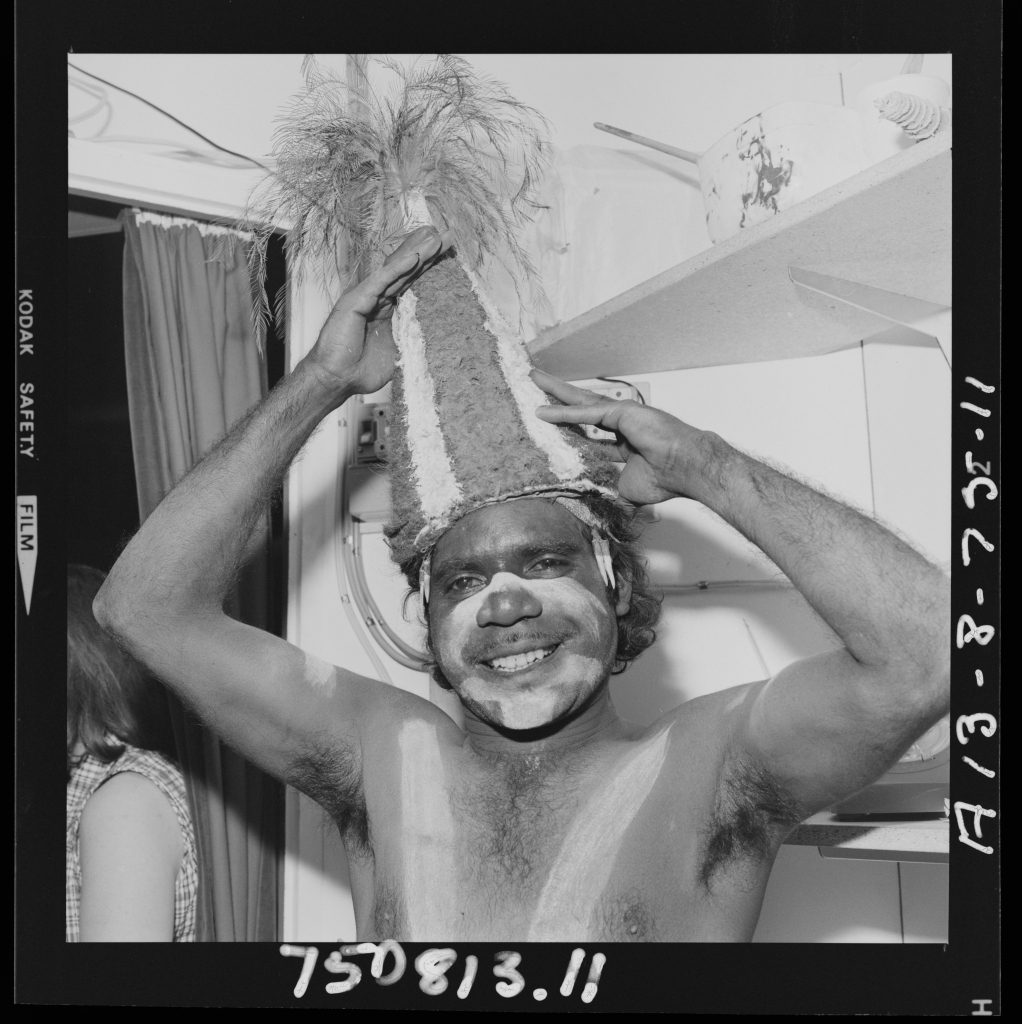

This exhibition contains a selection of the Indigenous news photographer Mervyn Bishop. Of all the photographers here, he was most concerned with the consent and cooperation of his sitters, and when looking at his photographs it is always fascinating to plot the various directions of their eyes and trace the interaction of their gazes. In 1975 he made his most famous photograph, which shows Prime Minister Gough Whitlam pouring sand into the hands of traditional Northern Territory landowner Vincent Lingiari, but in this instantly recognisable Australian ‘icon’ the gazes of Whitlam and Lingiari glance off each other. The year before, at the Royal Queensland Exhibition, however, a backstage Mornington Island dancer adjusts his ceremonial headpiece while looking happily and openly at Bishop. He’s pumped, ready to perform a traditional dance for the crowd at the ‘Ekka’. In the same year at Yarrabah, Queensland, a young girl is emboldened to return Bishop’s stare, assertively parrying the government camera’s gaze.

Mornington Island dancer sharing Lardil culture with audiences at the Brisbane Exhibition, 1975. Photographer Mervyn Bishop. NAA: A8739, A13/8/75/11

Staring down the photographer on a bus, Yarrabah, Queensland 1974. Photographer Mervyn Bishop. NAA: A8739, A26/8/74/25

Other photographers attempted to impose a tighter, more controlled choreography on their subjects. Neil Murray, who trained as a civil engineer, must have spent hours carefully placing his models, who hold their poses like mannequins, in his perfectly engineered compositions. It’s like watching a Jacques Tati film as our eye is led into the evenly lit transit lounge of Trans-Australia Airlines at Essendon Airport, Victoria, photographed around 1946; or through the impossibly clean 4-kilometre-long assembly line of the Ford Motor Company, Broadmeadows, Victoria, in 1960.

Trans-Australia Airlines lounge, Essendon Airport, Victoria c. 1946. Photographer Neil Murray. NAA: A1200, L3864

Cars move along the 4-kilometre assembly line at the Ford Motor Company, Broadmeadows, Victoria 1960. Photographer Neil Murray. NAA: A1200, L34225

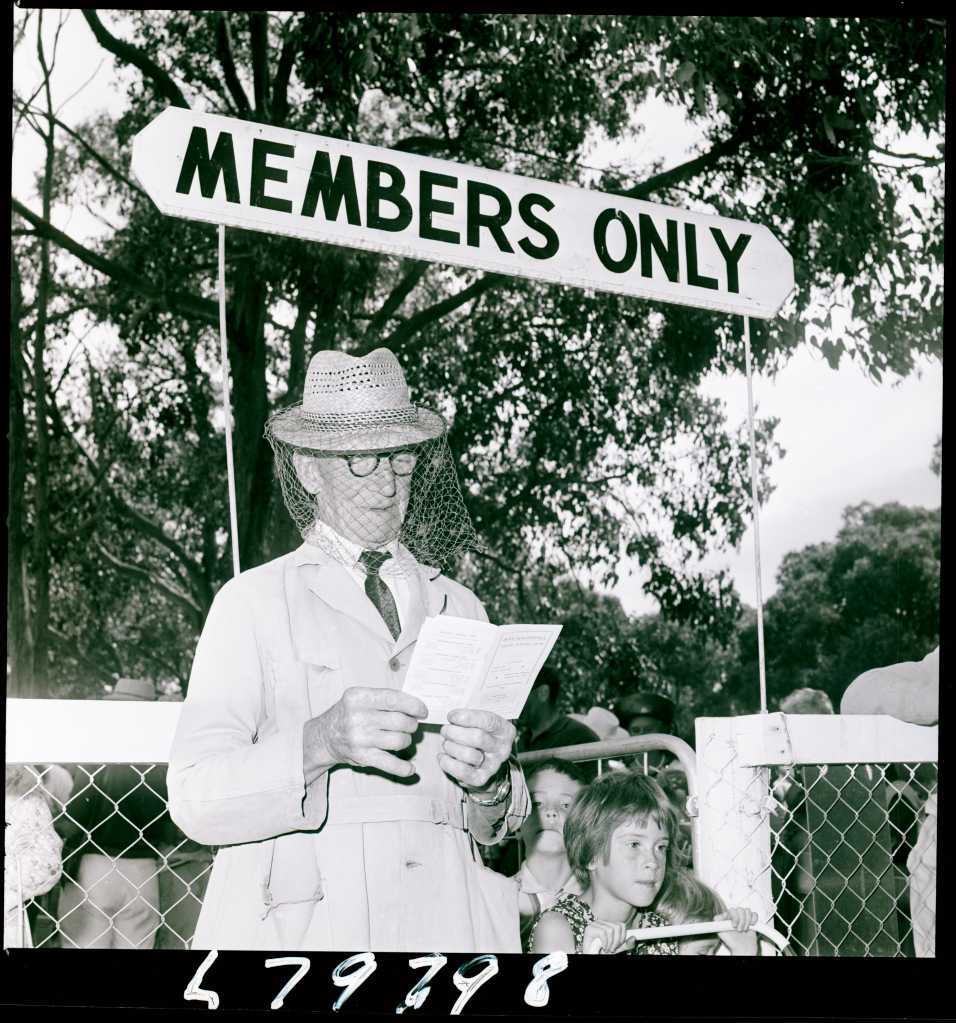

Keith Byron, who spent some time in the United States, also had an acute eye for composition. But sometimes small, contingent details intrude themselves. In 1969 his eye was caught by the picturesque betting man in the Members Only enclosure at the Balnarring picnic races, who has sensibly covered his hat with a fly net. But we, the viewers, can’t help noticing the kids, led by a young girl, squashed against the gate behind him, who have also been caught by Byron’s powerful flashgun.

Veteran punter outsmarts flies in the Members area at the Balnarring Picnic Races, Victoria 1969. Photographer Keith Byron. NAA: A1200, L79798

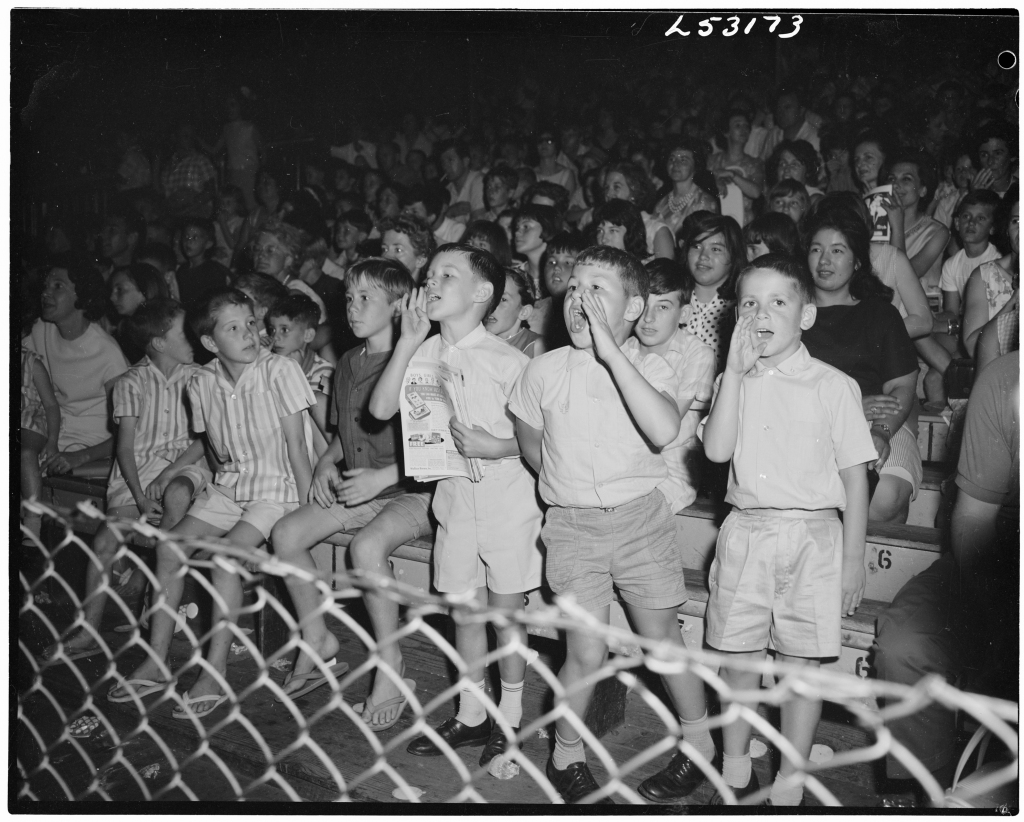

The flashgun was also frequently used to good effect by Bill Pedersen. For example, it picks out the front row of a young crowd who are all shouting at their visiting hero, Koichi Ose, who plays Shintaro in the Japanese samurai TV show Shintaro, enormously popular with boys of a certain age in 1965. But the presence of the government camera has distracted one young fan from Ose’s sword feats, and his eyes briefly slide off to the photographer himself as the flash goes off.

Young fans call out to Shintaro (Kiochi Ose), star of the Japanese television show The Samurai, as he performs feats with his sword, Sydney 1965. Photographer Bill Pedersen. NAA: A1200, L53173

Bill Brindle, who had worked for the Australian Women’s Weekly before joining the Department of Information, also had an eye for the theatrical. In 1958 he had a woman jump into the air to release two weather balloons outside St James Theatre on Melbourne’s cinema entertainment strip in Bourke Street. She is advertising an Australian Commonwealth Film Unit short film about the Giles Weather Station, Balloons and spinifex, which has been chosen to support the cinema’s main feature All at sea, yet another wheezy comedy from England’s venerable Ealing film studios. In Brindle’s photograph a row of five men, presumably from the Commonwealth Film Unit, look on and dutifully enjoy the stunt. But, out of focus in the background behind this slightly surreal scene, passers-by turn and stare, or in the case of one smartly suited woman, stride away up the street.

Posing with weather balloons outside the St James Theatre & Metro on Bourke Street to promote the screening the Australian Commonwealth Film Unit and Bureau of Meteorology documentary, Balloons and spinifex, Melbourne 1958. Photographer Wilfred Brindle. NAA: A1200, L26100

In another slightly stilted Bill Brindle photograph, staged at the Oenpelli (Gunbalanya) mission in the Northern Territory, a line of young Aboriginal men along a stockyard railing have been told to cheer on an older Aboriginal stockman who is breaking in a horse for the camera. Brindle had to use two sheets of large-format film to get the right combination of rearing horse and line of waving hats. But despite this careful choreography it is the three young Aboriginal kids at the end of the row, who don’t yet have hats to wave and wrap their legs around the top rail in squirming apprehension, who most engage our attention.

Stockman breaking in a horse at the Oenpelli (Gunbalanya) Church of England Mission in Arnhem Land, Northern Territory 1950. Photographer Wilfred Brindle. NAA: A1200, L13068A

For contemporary viewers it is these insistent incidental details and fragmentary occurrences, extraneous to the photographer’s original intention or initial government assignment, and resistant to cataloguing, tagging or even, perhaps, AI, which open out the archive to the true pleasure and value of these photographs.

Sometimes the photographer themselves seems to subvert their own publicity message. For instance, all the men posed studiously checking on quality control in Eric Wadsworth’s various factories, from a Toyota car parts factory in Altona, Victoria, to a Prestige stocking factory in Brunswick, Melbourne, seem to be ‘on message’ – in authoritative command of the industrial process. But our hearts go out to the poor worker woman, bent over her machine, sewing the massive thick orange blankets that are beginning to engulf her at the James Miller carpet factory, Warragul, Victoria, in 1971.

Machinist at work at the James Miller carpet factory, Warragul, Victoria 1971. Photographer Eric Wadsworth. NAA: A1500, K28661

Photographs like this, where the glowering orange of the blankets is fundamental to its impact, demonstrate how quickly the photographers became adept at deploying colour which was increasingly required by publications. Colour is intrinsic, for example, to the outback photographs of Mike Jensen, the 35 mm off-the-cuff street-life photographs of John Houldsworth, or to the fashion photographs of Bill Payne.

The idea of professionally skilled photographers employed as public servants to serve Australia’s publicity interests at home and abroad made it through to 1996, when it finally fell victim to government ‘cost-cutting’. Only Norman Plant, who had caught his passion for photography in his father’s amateur darkroom with a box brownie, before studying at the Royal Melbourne Institute of Technology and working in photography studios and as photojournalist, and who had been a government photographer for 28 years, was left to turn out the lights. Publicity photography was thereafter outsourced for specific projects and now, of course, almost 30 years later, young PAs handle ‘the socials’ from their smart phones.

The vast, systematic archive these government photographers built over five decades will continue to be used by historians and researchers for the historical information it contains. And it will continue to release its micro-secrets – the wayward glance of somebody’s eyes, the way they held their body, their fleeting expression, the patterns they made as they congregated together, and so on. But it is only able to give us all this because of the work of the original photographers. They weren’t geniuses, they weren’t special, they were professionals doing their job. They were public servants.

Martyn Jolly