Photofile

Vol. 95, Spring/Summer, pp48-55.

(with Daniel Palmer)

Australia’s big galleries and libraries have been seriously buying and curating photographs for over forty years now, during a period when the medium itself has undergone profound transformations. It’s time now to take an overview of the interaction between the institutional imperatives of our state and national collecting institutions and the changes in photography as a medium.

Although the institutional curating of photography did not begin in earnest until the 1970s, in the five or so decades before then the powerful idea of collecting photographs was intermittently discussed, at various levels of institutional authority, and with various degrees of vigour. For instance, at the end of the First World War, the amateur photographic magazine the Australasian Photo Review called for a ‘national collection of Australian photographic records’. The Mitchell Library was one of several institutions who responded positively to this idea, even suggesting a list of twelve different categories of photographs which amateurs could take for a future repository. However the librarians did not follow through on their initial positive noises and collections failed to materialise.

Thirty years later, at the end of the Second World War, the idea of a national collection was raised again. Laurence le Guay, the editor of the new magazine Contemporary Photography, devoted an entire issue to new sharp bromide enlargements Harold Cazneaux made from his Pictorialist negatives of Old Sydney, and declared that they ‘would be a valuable acquisition for the Mitchell Library or Australian Historical Societies.’ However, once more the library failed to follow through, and Cazneaux’s photographs remained uncollected.

Nevertheless, the interest in photography as an Australian tradition and the persuasiveness of the idea of significant public collections of historic photographs continued to build. By the 1960s both libraries and state galleries were beginning to make serious policy commitments to collecting photographs. The aims were to both collect photographs as documents of Australian life, and to record the importance of photography as a visual medium. For instance, the National Librarian of Australia, Harold White, began to work with Keast Burke who in 1956 had proposed a two tier national collection: one part to be purely about the information which photographs contained, and assembled by microfilming records and copying images in the library’s own darkrooms; the other part to be about the medium itself, made up of ‘artistic salon photographs’ and historic cameras.

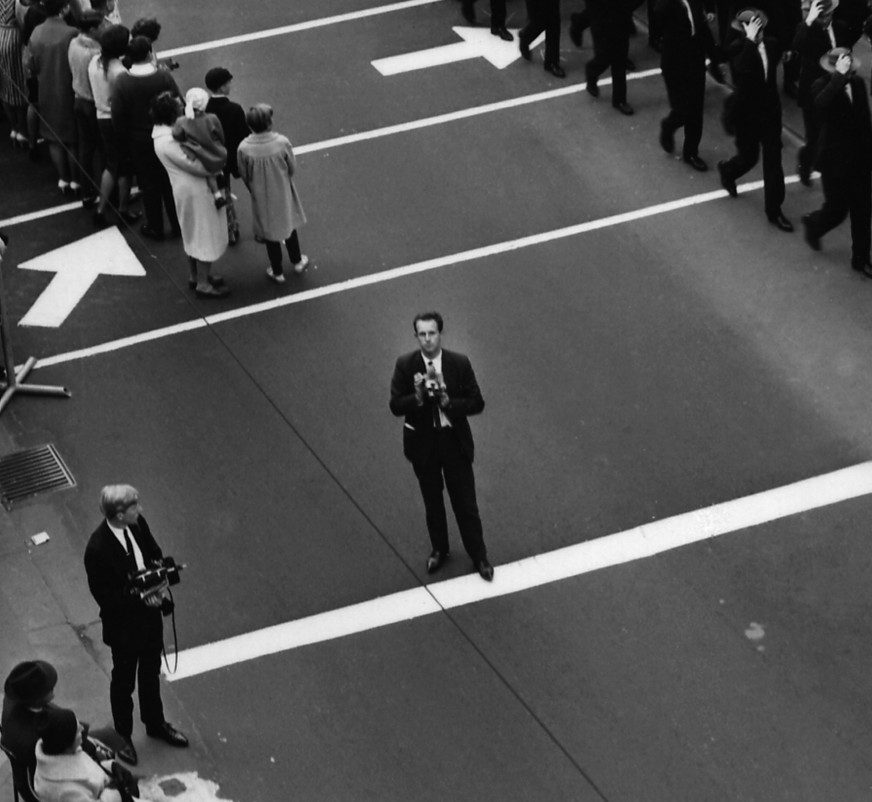

The National Gallery of Victoria, under Director Eric Westbrook, became the first state gallery to collect photography. Despite forthright opposition from some members (one of whom referred to photography as “cheat’s way of doing a painting”), the Trustees approve the establishment of Department of Photography in 1967.[ii] The first work to enter the collection – David Moore’s documentary photograph Surry Hills Street (1948) – was acquired through a grant from Kodak. In the same year the NGV imported The Photographer’s Eye, a touring exhibition from New York’s Museum of Modern Art, which had been the first art museum to establish a Department of Photography in 1940.[iii] The exhibition was curated by MoMA’s John Szarkowski, undoubtedly the most influential photography curator of the second half of the twentieth century, as a statement of his formalist position on photographic aesthetics. Its title was adapted for a local version, The Perceptive Eye (1969–1970).

By 1973 the yet-to-be-opened National Gallery of Australia had purchased its first photograph, an artistic confection by Mark Strizic (Jolimont Railway Yards, 1970) that looked more like a print than a photograph. Two years later the AGNSW was laying the foundation for its collection with the acquisition, exhibition and book on the early twentieth century photographs of Harold Cazneaux, collected by them as fine-art Pictorialist prints, rather than as the sharp bromide enlargements that had been published by Contemporary Photography in 1948.

In this period the dual nature of the photograph as both a carrier of historical and social information, and an aesthetic art object and exemplar of a tradition, which had co-existed within the formulations of the previous decades, was finally separated between libraries and galleries. Library collecting focused on the photograph as a document of Australian life. For example in 1971 the National Library of Australia clarified its collection policy: it would only collect photographs as examples of photographic art and technique from the period up to 1960, leaving post-1960s ‘art for art’s sake’ photography to the new state and federal gallery photography departments.[iv]

The stage was set for the much-vaunted ‘Photo Boom’ of the 1970s, when, as Helen Ennis has pointed out, the baby boomer generation turned to photography for its contemporaneity in the context of a counter-cultural energy.[v] Galleries and libraries found themselves embedded in the newly constructed infrastructure of the Whitlam era: the newly established Australia Council, rapidly expanding tertiary courses in photography, new magazines and commercial galleries, and the establishment of the Australian Centre for Photography in Sydney in 1974.

In this context the need to define photography as both a tradition and a new language became more urgent. Such initiatives were largely driven by photographers themselves, whose leading figures made themselves aware of what was happening internationally. Thus Athol Shmith, a key member of the NGV Advisory Committee set up in the late 1960s, corresponded and travelled regularly to Europe. David Moore, one of the key figures in the establishment of the ACP, was familiar with plans for the International Centre for Photography in New York. The first director of the ACP, Graham Howe, was brought back from a stint at the London Photographers’ Gallery. Developments were typically framed around a broadly didactic mission: that photography is central to visual culture but ‘the public needs educating’ in the art of photographic seeing. In addition, the longed-for acknowledgement from overseas materialised in the form of John Szarkowski himself, who was invited on a ‘papal’ tour by the ACP in 1974. Szarkowski gave six public lectures titled “Towards a Photographic Tradition’ (recently recounted in Photofile Vol 93). The purpose of the national tour, as Howe put it at the time, “was to liberate photography from the world of technique and commerce and to suggest that it could also be of absorbing artistic and intellectual interest.”[vi]

Although Szarkowski’s approach was put under sustained stress during the period of postmodernism – especially by feminist critics – his ‘formalist’ approach to the medium continued to dominate the way that photography was understood in the art museum for the ensuing decades. Even as the discourse emerged of an Australian tradition with, for instance, the NGV’s investment in Australian documentary photographers in the late sixties, this became embedded in a model of Euro-American modernism. As Ennis put it, “The argument for ‘photography as art’ was based on the critical position of Modernism. Photography was considered to be a medium with its own intrinsic characteristics”.[vii] At the AGNSW Gael Newton deployed a clear art historical teleology, with the acquisition of Pictorialist photography by Harold Cazneaux and other members of the Sydney Camera Circle forming the foundation for the collection. Pictorialism was important to Newton because it was a: ‘conscious movement, aimed at using the camera more creatively’[viii] Her exhibitions of Harold Cazneaux and Australian Pictorial Photography in 1975 closely followed by a monograph on Max Dupain in 1980, seen as the modernist successor to the Pictorialists. However, the galleries also engaged with the contemporary art photography of the graduates from the new art schools, as well as emerging postmodern ideas. For instance the title of the Art Gallery of New South Wales’ 1981 exhibition Reconstructed Vision defined this new style of work against, but within the overall trajectory of, the newly established historical traditions.

In Melbourne a slightly different but equivalent art historical strategy was taking place within the institution of the NGV. This included the mass importation of canonical images from overseas. For instance, shortly after her appointment, the NGV’s inaugural curator (and first ever curator of photography in Australia), Jennie Boddington, ordered Farm Security Administration re-prints from the Library of Congress’s reproduction service. However at the same time the NGV also held solo exhibitions by the young, art school-trained artists Carol Jerrems in 1973 and Bill Henson in 1975.[ix]

While galleries were using art historical strategies to embed photography within their structures, libraries were also confirming their commitment to photography, but as a non aesthetic-object based, content-driven, curatorial strategy. The contemporary cultural relevance of the subjectivist photo boom of the seventies, combined with Modernist and Postmodernist teleologies, drove the aesthetic strategies of galleries, but the nationalistic socially cohesive agendas of events like the 1988 Bicentenary drove the content-based strategies of library photo collecting. In a forerunner to today’s participatory online photographic projects, in 1983 Euan McGillivray and Matthew Nickson proposed a snapshot collecting project, Australia as Australians Saw It, which would copy photographs in the possession of individuals, then index them and make them accessible through the latest technology. During the Bicentenary year Alan Davies, curator at the State Library of New South Wales, travelled to twenty-three country towns and copied about seven thousand vernacular photographs from 576 individuals. Under the title At Work and Play, they were made accessible by a videodisc keyword search (a forerunner to today’s digital database).

Fast forward to the present. Over the intervening 40 years, since the establishment of various departments and the ACP, the boundaries of photography have expanded. However, galleries have largely kept to the historical trajectories inaugurated in the 1970s. In the 1980s, photographic reproductive processes became central to postmodern art, which had the flow-on effect of boosting photography’s place in the art museum (Tracey Moffatt, Bill Henson, Anne Zahalka, etc.). But postmodernism did not fundamentally alter the increasing focus of departments of photography on ‘art photography’. Indeed, as many writers have observed, the wholesale acceptance of photography as art by the institutions and market occurred precisely at the moment of the critique of art photography, as it had been defined within the ‘formalist’ tradition, by artists and postmodern critics.

Photography’s potential as a protean medium to disturb or at least promote a dialogue between institutional disciplines and ordering systems has only rarely been explored by curators. Perhaps the most notable is the disruptive placement of contemporary Indigenous work, like Brook Andrew’s Sexy and Dangerous (1996) – which appropriates an image by the Charles Kerry photography studio – within galleries of nineteenth-century colonial painting at the NGV. Into the 1990s and 2000s, departments of photography essentially continued a monographic and consolidation phase, aided by the international prominence of large-scale colour photography as art, such as the Düsseldorf School (including photographers such as Andreas Gursky), or what Julian Stallabrass dubs “museum photography”.[x]. Meanwhile, we have seen the ongoing integration of photography as part of interdisciplinary art practice which may also include sculpture, performance or installation (sometimes dubbed the ‘post-medium condition’). Simultaneously, we have witnessed the rise of digital photography, which has produced a whole new generation of photographers using online photosharing services like Flickr and Instagram, whose effects are much more widely felt outside the museum. In response to these complex historical changes libraries have invested institutional effort into digitizing their image collections and making them available online, while art museums have embraced photography’s status as an object to be experienced in the flesh, hung in exhibition galleries.

If the primary aim of photography curating in the 1970s was to establish photography as art, this has clearly been achieved. Photography is ubiquitous within contemporary art, but not as an autonomous tradition – rather as a mode integrated within wider practices. And if the now forty-year old institutional structures are still largely with us, if museums continue to have departments, curators and galleries of photography, this is largely for the history of photography, for the knowledge of specific collections and conservation techniques. However, even if photography is now deeply embedded in the art museum, its precise role is still up for grabs. For instance, in 2013 the dedicated photography gallery at the NGV International was given up without any controversy (along with prints and drawings). In the early 1970s, photography enthusiasts had fought for a dedicated area, even just a corridor outside the Department of Prints and Drawings in 1972.[xi]Recently, in a delicious irony, the former photography space was occupied by Patrick Pound’s installation The Gallery of Air (2013) – which the wall label described as a poetic “site specific installation comprising 91 works from the collection of the NGV and 286 works from the collection of the artist” organized around the idea of air. Pound’s work included a wide variety of media in its playful exploration of collecting (both personal and institutional), but its inspiration lay in photography’s role as an ordering system. Various inclusions (such as Man With a Tie) were included in a previous work of found photographs, Portrait of the Wind (2010).

Clearly, museum departments can no longer work in isolation. However, what the mere integration of photography into the newly contemporary art museum all too easily elides is that photography’s place there has always been unstable, its ambiguous status as object and information continually threatening the grounds of the art museum’s hierarchies and collection policies. This instability manifests itself in different ways in different periods, but as we have already hinted at, one of the underlying themes in photography in the museum is the constant exclusion of the vernacular and of reproducibility itself. As Douglas Crimp argued in the late 1970s, the inclusion of photography within the canon of modernist art practice, by its own logic, excludes photography as reproduction.[xii] We have seen this in Australia in relation to the location of photography between the library and the art museum, in terms of a split between information and aesthetics, a documentary database versus an aesthetic object. Photography’s recent insertion into digital networks reveals these tensions yet again, in a new guise. Within a modernist logic, the networked digital image, circulating as reproducible information, is guaranteed to be excluded. The potential for different kinds of photography in the art museum goes largely unnoticed.

It could be argued that similar issues are faced by other Departments such as Painting, in the ‘post-medium’ age. And indeed that the sway of the MoMA Photography Department could be compared to the influence of the massively influential travelling show Two Decade of American Painting in 1967. However, we argue that the protean and unstable nature of the medium of photography makes its placement more problematic. As a result, within the rapidly growing discourse of curating contemporary art, we argue that more attention needs to be paid to the specific situation of photography and the history of photography exhibitions. This is not to regress into conventional medium specificity. It is simply to acknowledge that photography’s multiple, democratic and ambiguous presence as image and object within our culture complicates its place in the art gallery. Photography as a creative art has a more or less integrated tradition that we can and should continue to value because it drives further developments. But we should simultaneously recognize that this tradition is based on a series of exclusions, and addressing these exclusion can also energize the medium. As Peter Galassi once put it, the tradition is both indispensable and inadequate.

In identifying the future potential of photography in the art gallery, perhaps we can learn from the popularity of ‘metaphotographers’ such as Patrick Pound, working with the (always incomplete) archive.. Furthermore, if curators are engaged in creating innovative contexts for public engagement, networked photography opens up new possibilities for this to happen. We are not arguing that the art gallery ought to emulate the hyper-linked experience of the Internet, or the swipe-based logic of mobile media. However, we are proposing that authoritarian presentations of a connoisseurial canon need to become part of a larger project: exploring photography’s protean nature as a medium and its potential to complicate spectatorship and activate audiences in new ways.

Daniel Palmer & Martyn Jolly

[i] This essay derives from early research into the various forces currently influencing photography curating in Australian art galleries, funded in the first instance by an Australian Council grant.

[ii] Isobel Crombie and Susan van Wyk, 2nd sight: Australian photography in the National Gallery of Victoria (Melbourne: National Gallery of Victoria, 2002), 7.

[iii] Founded in 1929, MoMA presented its first photography exhibition in 1937 (the major Beaumont Newhall exhibition on the history of photography in 1938–1937). MoMA held their first one-person exhibition, by Walker Evans, in 1938, and established their Department of Photography in 1940, then the only one in any art museum.

[iv] Helen Ennis, ‘Integral to the Vision: A National Photographic Collection’ in Peter Cochrane (ed.), Remarkable Occurrences: The National Library’s First 100 Years (Canberra: National Library of Australia, 2010), 210

[v] See Helen Ennis, ‘Contemporary Photographic Practices’ in Gael Newton, Shades of Light: Photography and Australia 1839–1988 (Canberra : Australian National Gallery, 1988), 134.

[vi] Graham Howe, ‘The Szarkowski Lectures, Art & Australia, July–September , 1974, 89.

[vii] Ennis, ‘Contemporary Photographic Practices’, 136.

[viii] Gael Newton, Silver and Grey: Fifty Years of Australian Photography 1900-1950 (Sydney: Angus and Robertson, 1980), np

[ix] In Canberra the National Gallery not only purchased photographs from young art-school trained Australian photographers through the largesse of the Phillip Morris Arts Grant, but also, in 1980, before it even opened, gained Ministerial approval to spend $150,000 for the Ansel Adams Museum Set from an American gallery.

[x] Julian Stallabrass, ‘Museum Photography and Museum Prose’, New Left Review, no. 65, September-October 2010, 93–125.

[xi] Crombie and van Wyk, 2nd sight, 10

[xii] Douglas Crimp, ‘The Museum’s Old/The Library’s New Subject’ in Richard Bolton, ed., The Contest of Meaning: Critical Histories of Photography (Cambridge MA: MIT Press, 1989), pp. 3-13. See also Andrew Dewdney, ‘Curating the Photographic Image in Networked Culture’ in Martin Lister, ed., The Photographic Image in Digital Culture, Second edition (London: Routledge, 2013), 95–112.

Antecedents - Mallee Routes

Adelaide Photography 1970-2000: Submissions called - Thought FactoryThought Factory