‘A Brief History of Photofile’, Photofile, No. 50, 1997

Recalled Photofile/Potted Photofile

Photofile now fills three magazine boxes on my shelves and I have been involved with it in one way or another for virtually all of its history. However it was always too precariously funded, too open to the vicissitudes of arts politics and policy, and too subject to the recurring paroxysms of the ACP itself, for it to have ever achieved a stable existence for a substantial period of time. So, despite its relatively venerable age of fifty issues, it has never achieved the consistency to have been a barometer of the changing Zeitgeist, or even an authoritative record of its historical period.

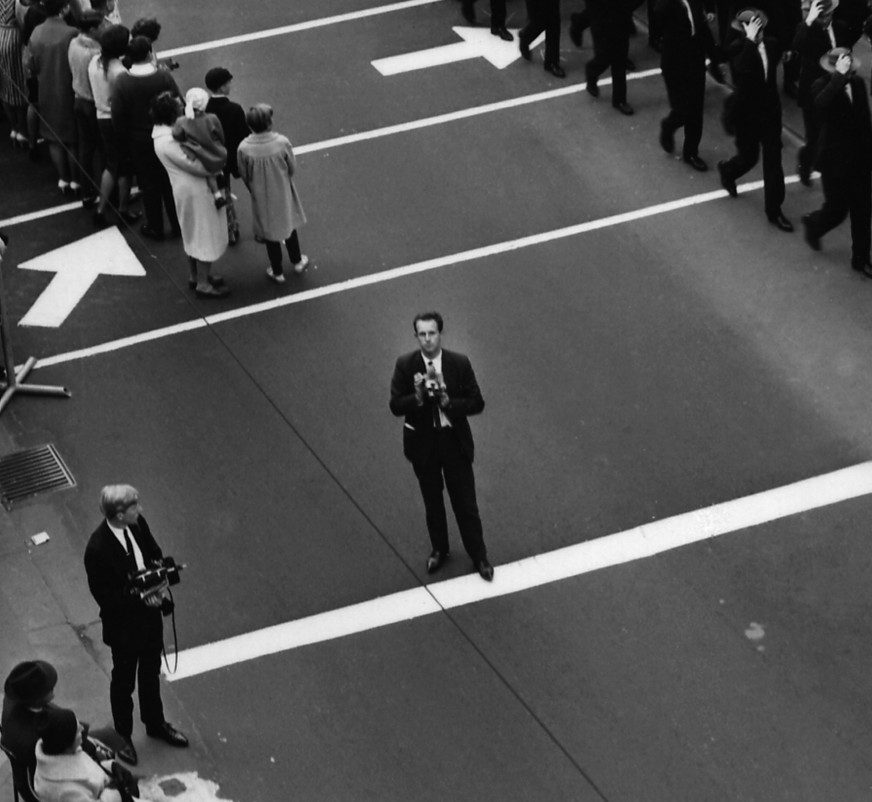

Nonetheless I think it is an invaluable repository of Australian writing from the last fifteen years. If fifty issues of Photofile do not quite make a full blown archive, at least they form a fascinating and densely packed midden. Before I went back to my magazine boxes I tried to list all of the articles in Photofile which I could readily recall to mind. Some had stuck in my memory because I had enjoyed reading them, and they had struck me at the time as interesting models for establishing both a personal and a theoretical relationship to the medium. For instance I remembered an article which Judith Ahern wrote and illustrated, very early on in Photofile’s history, about Sydney’s last commercially practising street photographer. Judith had interviewed Cecil Maurice who had detailed memories of this almost forgotten form of street hawking which uncannily echoed the art practice of street photography, (‘Memoir of a Street Photographer’, Summer 1984). I remembered Anne McDonald’s (now Anne Ooms) Barthesian meditation which teased apart strands of personal memory, colonisation and patriarchy in a photograph taken by her father in New Guinea in the sixties, in which she herself appears in the background as a young girl, (‘Girl Dancer at Rigo Festival’ special South Pacific issue Spring 1988). I remembered Paul Foss’s scrupulously close reading of Robert Mapplethorpe’s Man in a Polyester Suit 1981, which was on display in Australia at the time, (‘Mapplethorpe Aglance’, Spring 1985). And I remembered several other similar articles such as Roslyn Poignant’s history of a famous photograph by her late husband Axel Poignant—which she methodically tracked from her personal recollection of being there when the photo was taken to seeing it electronically altered on the cover of a conference program decades later, (‘The Swagman’s After Image’, #35). It is clear to me that articles such as these would have never been written if Photofile didn’t exist.

I can readily recall many others Photofile articles because I have had occasion to frequently refer back to them in my teaching. They are still the best reference points for recent Australian photographic history and theory. For instance I still use Adrian Martin’s excellent articles on Bill Henson and then Anne Ferran (‘Bill Henson and the Devil, probably’, Spring 1885, and ‘Immortal Stories’ Summer 1986); Helen Ennis’s feminist revision of the 1970s Australian photography (‘1970s Photographic Practice a Homogenous View?’, Autumn 1986) and others by Geoff Batchen, Helen Grace, Catriona Moore and so on. These important articles may possibly have found homes in other magazines or as forum papers, but many would have undoubtedly simply remained brewing on their author’s mind if not for Photofile.

What all these memorable articles have in common for me is that they were all well written, and all directly engaged with specific photographs and practices, whilst bringing an additional point of reference—personal, theoretical, historical, political—to bear.

With my mnemonic experiment completed I methodically flicked through all forty-nine of the previous issues. I detected an overall historical shape to the magazine. And Photofile definitely had clear high points and low points. When it first appeared in 1983 its mere existence seemed, to some, to be achievement enough. However these ‘tabloid newspaper’ issues do not compare favourably with the sense of excitement generated by other Australian art magazines on the market at that time: for example Art Network, which had already done an excellent special issue on photography before Photofile even began; On The Street, which seemed to be on much more intimate terms with its readership than Photofile ever was; and of course Paul Taylor’s theoretically savvy Art & Text.

Although Australian photography had institutionally matured—with curatorial departments, art school departments and exhibition venues all well and truly in place—it was still relatively impoverished and insular as an autonomous discourse. So there is a sense of overdue, but aimless, stocktaking in these early issues: rambling prolix interviews with curators and ‘made it’ photographers; protracted avuncular sermons on overly generalised topics of art, photography and history; descriptive reviews and news; and quaintly colonial sounding ‘letters’ from interstate and overseas. There is also a residual anxiety over the status of photography as a self-sustaining discipline. This was anachronistic in a cultural climate where photography as a medium had become the main arena in which wider debates about representation, simulation, gender, and power were being energetically played out.

Some of the most entertaining writing in these issues is, ironically, by Max Dupain, who was still writing scourging reviews for the Sydney Morning Herald at the time. In these Photofiles, when most articles seemed to have been written off the top of the head, Dupain’s crazy mixed metaphors and passionate declarations of radical conservatism are in their element. See, for instance, his ‘Photography in Australia, A Personal Progress Report 1978-1984’ from the Tenth Anniversary of the ACP issue, Summer 1984.

For me the high point of the magazine so far has been the issues edited by Geoffrey Batchen in 1985 and 1986. Photofile finally caught up with the boat the earlier issues had missed. Important debates were pursued with vigour and rigour from an enlarged and deepened pool of writers who drew on skills from outside the narrow confines of photography qua photography. The letters pages livened up. The magazine went to A4 and reproduced images on a slightly more generous scale. And the magazine quickly achieved a vividness which belied its rather dour black cover.

During the subsequent three years editors Catherine Chinnery and Robert Nery, and a series of guest editors, maintained the essential A4 format. But by the late eighties the single photograph was no longer automatically the central player in the ongoing drama of cultural politics. And photography as an art discipline was dispersing in all directions under the impact of technological change. Photography’s role in culture became increasingly difficult to describe without access to the vast discourses of the mass media, history, and psychoanalysis. It became increasingly difficult to think about photography as a contemporary visual art without also thinking about film, video or installation. Photofile gamely grappled with this Hydra while attempting to maintain its brief as the journal of the ACP and its obligations to its primary constituency of photographers. (Whose interest in Photofile, it must be said, increased dramatically whenever their shows were, or weren’t, reviewed in it.)

However during this period Photofile managed to publish a loose group of articles which dealt in various ways, with emerging problems of history and the archive, the photograph and the historical document, and the image and time. A highlight of this period was a double issue on the South Pacific guest edited by Ross Gibson, (Spring 1988). In retrospect these diverse articles which appeared spread over many issues, by writers such as Elizabeth Gertsakis, Paul Carter, Ross Gibson, Graham Forsythe and Sylvia Kleinert defined the flavour of these issues—just as the articles on gender, representation and cultural politics by writers like Paul Foss, Adrian Martin and Helen Grace defined the flavour of the previous issues. They formed a strong thread running through these issues which it is difficult to imagine appearing in any other Australian journal at the time.

During this time also Photofile moved haltingly towards limited colour, became more design conscious, experimented with artists pages, and began to use images as autonomous units rather than addenda to a predominant text. However its continuing anxieties of self-definition spun out of control in a disastrous series of issues edited from Melbourne in 1990 and 1991. What appears to be unprecedented access to sponsorship and design know-how was squandered on gratuitous design follies, an attenuated relationship between text and image, and many arcane, obscure or irrelevant articles with little relationship to contemporary Australian photography.

Fortunately subsequent editors, Martin Thomas, Jo Holder and George Alexander re-grounded the magazine, while retaining its contemporary design feel. Looking back over these last sixteen issues one can clearly see, of course, the emergence of cyberculture as a major preoccupation, but also the continuation of concerns that Photofile has consistently covered right from 1985: the body, history and—as a steadily increasing concern throughout its history—race. There is no longer so much of a sense of grim struggle with all the multiplying issues that photography continually brings up and all the continually sub-dividing media which impact on it. Recent Photofiles have, I think successfully, engaged with selected aspects of what is now a general area of visual and cultural discourse, rather than attempting to survey what is no longer a clearly definable medium.

Meanwhile the landscape around Photofile has changed beyond recognition. The art magazine field has shrunk, and has shifted towards the mainstream. General academic journals are now regularly discussing many issues of visual culture, and books and anthologies are being published in unprecedented numbers. Information about art is as likely now to come from the radio, a Saturday afternoon forum somewhere, or your computer, as it is from a mag (although newspapers remain as irrelevant as ever). Photography has become photomedia. Perhaps it’s time for Photofile to become something else too. (After it produces a complete index of itself.)

Martyn Jolly

January 1997

on photographic criticism in Australia - Thought FactoryThought Factory