‘Wolfgang Sievers’ Photographs: From the Future to the Past’, catalogue essay for Wolfgang Sievers 1913 — 2007: Work, curated by Stuart Bailey, pp 5 — 14, Glen Eira City Gallery, 2007.

One night in 1983 Wolfgang Sievers steadied himself on a tug as it heaved on the waves of Bass Strait and with a long hand-held exposure photographed an oil rig belching a giant tongue of flame and spouting a curtain of water. The experience was the high point of his career as a professional photographer. It was, in his own words, like the grand finale to a fantastic, dramatic opera. When Sievers saw the diabolical Wagnerian result, Inferno, Nymphea Oil Rig, Bass Strait, he thought that he couldn’t have done any better, and decided there and then that it was to be almost his last professional photograph[i]. But in making the decision to ‘stop whilst he was on top’ there was also an element of sourness and disappointment about the progress, or lack of progress, in Australian society, industry and architecture during the half-century his professional career had covered. As a bombastic vision of industrial power and excess the oil rig photograph was a long way from Sievers’ first industrial photographs. For instance it contrasts strongly with one of his favourite photographs taken in 1939 at the very beginning of his career in Australia, of the dipping of match heads at Bryant & May, in Richmond, Victoria. Although also of a toxic industrial process, this image had a delicate clarity that for him encapsulated the ideas of simplicity and functional beauty which he thought should underpin all of his work.

For Sievers, as for many of the other European artists, designers, photographers and architects who also fled to Melbourne to escape the rise of Nazism, the ideas of pure functional beauty they brought with them were inextricably linked to wider ideas of social progress. The political foment of 1920s Weimar Germany had given rise to the famous Bauhaus, which taught not only the importance of truth to function in design; but also the importance of unifying the artist and the designer, the machine and the worker, to forge a new future society. In the post-war period these ideas were to pervade the entire world through the global rise Modernism, but Sievers also had a direct connection to them through his years in the late 30s at Berlin’s Contempora School of Applied Arts, which was a small private school that had taken up the Bauhaus project after it was closed by the Nazis in 1933.

As a young man in Germany during the 1930s Sievers was inevitably caught up in, and forever formed by, the political events of the time. He moved to Portugal in 1934 to try to make a career as a photographer, but then became briefly involved in the Spanish Civil War against Franco, for which he was arrested by the Gestapo on his return to Germany in 1936. He was not Jewish, though his mother was a Jewish descent, but in 1937 he decided to arrange his emigration to Australia, using as one of his guarantors the documentary photographer Axel Poignant who himself had emigrated to Australia ten years before. He was forced to dramatically expedite his plans when the Luftwaffe called him up for two years service as an aerial photographer. He was given one day’s grace and immediately escaped to England.

He left Germany at the age of 25 steeped in the ‘New Objectivity’ style of photography: he had taken front-on, clear-eyed photographs of poverty in Portugal; he had taken deep-focussed architectural views of nineteenth-century palaces on behalf of his art-historian father; he had been commissioned by the contemporary expressionist architect and family friend Erich Mendelsohn to photograph the last of his buildings in Germany before he himself had fled for Britain in 1933; he had made advertisements for modern products such as sheer stockings, dramatically lit in the latest studio style; and he had made low-angled sunlit portraits of his fellow Contempora School students heroically looking into the future.

He arrived in Melbourne in 1938 and set up a studio in South Yarra with the latest photographic equipment which he had sent on ahead. But he found pre-war Melbourne to be very different to Berlin, and opportunities severely limited. He decided to specialise in industrial and architectural photography, where he could immediately apply what he had learnt about the purity of design and the essential honesty of the machine. He rapidly found several large clients, but from 1942 volunteered to assist in the Australian war effort. After the war Sievers’ career took off again, buoyed by Australia’s building and industrial boom. For his industrial clients Sievers provided shots for their annual reports, publicity brochures and advertising.

One of his biggest clients was the heavy engineers Charles Ruwolt, which were taken over by the British based company Vickers in 1948. A problem many industrial photographers faced was the visual mess and distraction of any factory floor. (This can still be seen in some of Sievers’ shots, such as the grim Sweatshop, Melbourne, 1958). The graphic designers of annual reports generally got around this problem by simply cutting the distracting background out of the photographs, often leaving a heavily airbrushed image of an odd-shaped piece of machinery floating isolated on the page with no sense of scale or drama. Sievers solved the problem photographically by either raising his camera to look down on the machinery, or lowering the camera to shoot upwards against the roof, and using his own lights to light the machinery whilst leaving the distracting background in darkness. For example in reality the Nordberg Crusher he photographed in 1969 was hemmed around with factory paraphernalia, but Sievers organised a thorough clean up of the area around the crusher and built a platform to elevate his camera, he then descended into the crusher with ladders to light its interior, emphasising its circular shape and its depth. As a bonus he wedged a dramatically lit lab-coated operator into the lower right hand corner for the final shot. The image then created its own graphic force and internal visual drama that could be used in any publicity situation. (According to Seivers himself the subsequent publication of the image in the financial press resulted in a multi-million contract for the company.)

Man and machine were Sievers’ quintessential subjects. To Sievers the essence of a good factory was not labour by itself, nor the technical process in isolation, but that ‘everything is as it should be’, with men directing machines efficiently, and each augmenting the other.[ii] In Sievers’ photographs the operators are functionally connected to the machine by their hands and their eyes — they peer through loupes, or pull levers, or intently measure the details of gigantic pieces of machinery with finely calibrated instruments. The image of a technician establishing the accurate positioning of a hydraulic pump crankshaft with a micro-alignment telescope, Quality Control at Vickers-Ruwolt, 1960, was published in a Vickers Ruwolt brochure. Running across the pages of the brochure in a kind of staccato modernist poem to industry were the words: “From a concentration of trained minds — emerges mechanical excellence … experience is combined with intelligence and work proceeds …from molten metal … to tools of high precision and great power …precision created out of precision … born in the toolroom … the climax—assembly and testing …”. [iii]

These sentiments of corporate pride were given an almost nationalistic resonance a few years later in another, even more constructed, shot for Vickers Ruwolt. In Gears for Mining Industry, 1967, an engineer, like an operatic hero ascending a stage mountain, climbs the teeth of a giant gear which has been especially raised upright by a crane, to steady with one hand and measure with the other the second half of the gear whose several tons has been suspended upside down above him.

During the 1970s and 1980s photographs such as these began their migration from the pages of company reports to the walls of art museums. In 1991 this image was one of four chosen by Australia Post to become a stamp to celebrate the 150th anniversary of Australian photography. It had become a fully fledged icon of Australia as an industrial nation, complementing other national icons such as Harold Cazneaux’s mighty gum tree The Spirit of Endurance, 1937, or Max Dupain’ Sunbaker, 1937, which encapsulated other aspects of the national myth — it’s land and its lifestyle.

However throughout his career there is a continuing visual tension in the respective role of worker and machine. His vision was clearly centred around the trained technician rather than the knockabout aussie manual worker, though he did love to photograph traditional workers who seem to have a heritage of noble labour going back centuries. For example in his 1962 image of a worker in the Miller Rope factory hefting the rough rope in his firm hands Sievers saw ‘the dignity of man … staring you straight in the face’. In other images, in contrast, such as Finishing of Hitachi Brand Valves for the Snowy Mountains Hydroelectric Scheme, 1967 or Coal Mining Dredges, Yallourn, Victoria, 1956, the technicians of the modern industrial age are squashed uncomfortably into tight corners by the looming bulk of the machine.

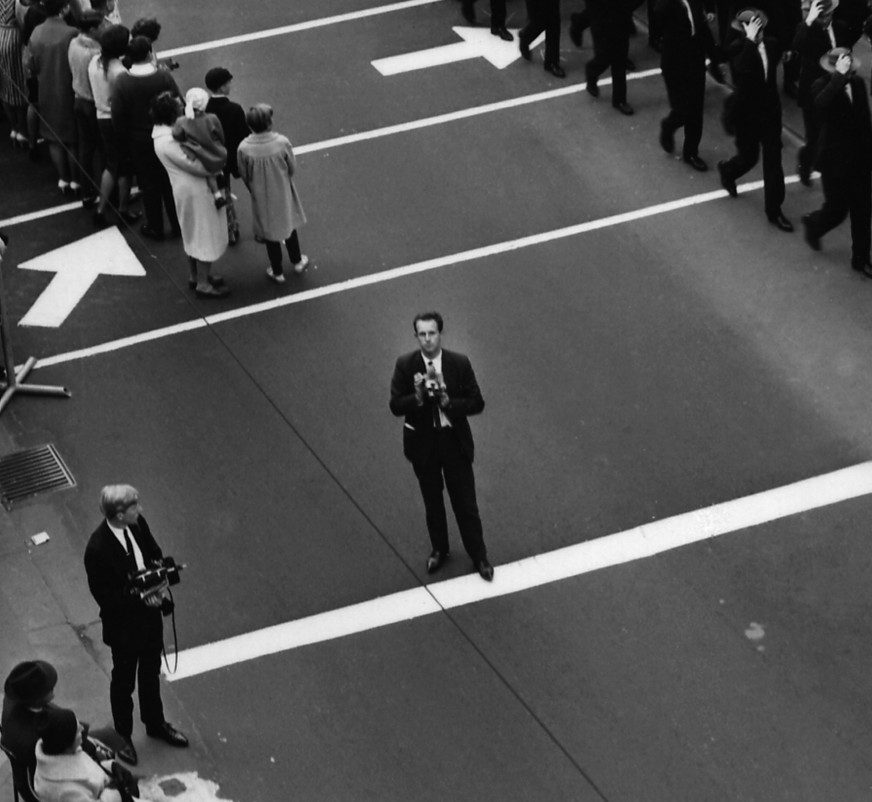

Workers by themselves, however, unconnected to any machine, rarely figure in Sievers photographs. He admits that his poor English initially made him scared of the human element, although later his bilingualism could be an advantage with Australia’s ethnically diversifying workforce. One of his rare photographs of workers by themselves and with their own autonomous personalities, is the crowd shot taken from an aerial point of view of the Shift Change at Kelly and Lewis, Springvale, 1949, where friendly workers smile and squint up at Sievers’ camera. Nowadays the idea of the dignity of manual labour has been grossly devalued, and corporations are unlikely anymore to be interested in commissioning photographs of their workers as a collective force. In this light the image now has an elegiac character, and reminds me of another Sievers’ aerial view with receding perspective, Old Frankfurt before its total destruction in World War 11, Germany, 1937 — both are photographs taken on the verge of destruction.

The metaphors of theatre or opera are the ones most commonly applied to Seivers’ industrial work. But other genres sometimes come to mind as well. For instance the dramatic side lighting used to apply strong shadows and bright sheens to the equipment in Lathe operator at Marweight, Burnley, Melbourne, 1968, not only isolates the lathe against a black background, but also gives the scene a B Grade Frankenstein appearance. Other shots, such as Sulphuric Acid Plant at Electrolytic Zinc, Hobart, 1959, could almost be described as industrial pornography as the gleaming steel tubes turn and curve in on themselves. (When it was reproduced full page and in full colour in the BHP book The Fabulous Hill, its caption was much more prosaic: ‘This new acid plant will bring Risdon’s capacity for the production of sulphuric acid to 170,000 tons a year.’)[iv]

As his career progressed the symbiotic relationship between his own ideals, forged in the Europe of the 1930s, and the reality of Australian industry swept up in the resources boom of the 1970s and 80s, began to pull apart. Sievers was always a political animal and proud of his past. In 1967, at the height of the Vietnam War, he placed a photograph of a GI holding up the severed head of a Vietnamese in his studio showcase window at the Collins Street entrance of the Australia Arcade. He accompanied the image, which had been taken from LIFE magazine, with the following sign: ‘I Wolfgang Sievers: victim of Nazi persecution — prisoner of the Gestapo —volunteer of the AIF and RAAF 1939 — volunteer Australian Army 1942- 1945 PROTEST against the undeclared war — against conscription by lottery — against imprisonment of conscientious objectors whose just stand has been laid down at the Nuremberg trials to be the duty of all men.’ As a result of this protest Sievers estimates he lost 60% of his industrial clients.[v]

Although they are certainly full of drama, Sievers’ photographs are devoid of any sense of noise, smell, dirt or toxicity. Floors have been cleaned, workers’ hands washed, and their chins shaved. Clean lab coats have been put on and 500-watt lights carefully positioned to obscure the ugly backgrounds. As Sievers himself admitted ‘industrial photography is lying most of the time.’ Increasingly, Sievers became concerned with the pollution that was produced by the industries that his photographs pictured as being pollution free, with ‘everything clean and wonderful.’ The worse it got, he said, the nearer he got to the end of his days as a photographer.[vi] He was also concerned with the foreign ownership of Australian resources.[vii] During the 1980s he concentrated more and more on retrospectives of his own career, as well as other historical and political interests.

Sievers was much more than just an industrial photographer, however. The artists, designers, architects and photographers who fled to Melbourne to escape Nazism made enormous contributions to Melbourne’s growth as a cosmopolitan city, and Sievers photographed much of it. For instance he made advertisements for the Prestige company which produced textiles designed by Gerhard Herbst who, like Sievers had trained in Germany and fled to Melbourne in 1939.[viii] Herbst also designed the striking poster advertising New Visions in Photography, a 1953 exhibition Sievers and another émigré photographer, Helmut Newton, held promoting their work as commercial photographers. A boldly designed sign in the exhibition announced: ‘the aim of this exhibition, the first of its kind in Melbourne, to demonstrate, through actual work done, the potential of industrial and fashion photography as a means of better promotion and bigger sales in business today.’[ix]

He also photographed the cutting edge modernist architecture of fellow émigrés Frederick Romberg, who arrived in Melbourne from Germany via Zurich in 1939 and also knew the influential expressionist architect Erich Mendelsohn; and Ernest Fooks who arrived in Melbourne in 1939 from Vienna where he was a progressive town planner and architect.[x] Like Sievers, both these architects saw their work as directly affecting the development of a socially progressive, technologically modern society. He photographed their work in the international architectural style, with dynamically receding horizontal lines, sternly orthogonal vertical lines, and cleanly isotropic spaces. These deeply-focused sharply-defined views of ideal modernist architecture could have been made at any time in any metropolis modernism had spread too— Europe, Japan, Canada, Brazil or Australia. Today they all seem uncannily empty and devoid of atmosphere, as though they are waiting for the future to happen

In the 1950s émigré architects designed many houses and modernist flats around the eastern suburbs of Melbourne. Sievers photographed the house Fooks designed and built for himself in Caulfield in 1966. His photographs beautifully capture the sense of the house experienced as a procession of enclosed and semi-enclosed spaces and courtyards from street frontage through to the garden, all modulated by Japanese inspired timber screens, an undulating timber ceiling, and detailed joinery — a testimony to Fooks’ Viennese heritage.[xi]

But, just as he had parted company with industry, Sievers also found himself parting ways from the mainstream of Australian architecture and design, where the ideal, designed future he envisaged appeared increasingly derailed by thoughtless and crass developments, which could be just as effectively photographed quickly with small format cameras. In 1988 he was invited out of his semi-retirement to photograph the new Parliament House in Canberra, but he refused because he did not approve of the design by the US architects Mitchell/Giurgola. Increasingly looking to the past, Sievers travelled to Berlin and Paris in 1989 to research war criminals who had also emigrated to Australia. Whilst there he briefly rediscovered his excitement in architecture as he photographed I. M. Pei’s newly opened pyramid entrance to the Louvre, with its spectacular and explicitly engineered glass walls.

Sievers’ work is now firmly ensconced in the nation’s image of its past. Art museums and libraries had consistently purchased his key images from the early 1970s onwards, and the National Gallery of Australia toured a major retrospective nationally in 1991 and 1992. In 2004 the National Library of Australia completed the purchase of his complete archive of 51,700 negatives and transparencies and 13,700 prints, which they are now in the process of digitising.[xii] His images, which were once about creating an ideal modern future for Australia, are now subsiding into the nation’s official past. The irony is that the future his photographs so keenly anticipated never actually happened. The wealth and prosperity they predicted certainly came, but the sense of social balance, equality and honesty, where ‘everything is as it should be’, which they were attempting to create, never really did. We can see that clearly now, but Sievers himself could feel it, twenty-five years ago.

Martyn Jolly

[i] Wolfgang Sievers, Wolfgang Sievers: Contemporary Photographers Australia, Writelight, 1998, np.

[ii] Photographers of Australia: Dupain, Sievers, Moore, Film Australia, 1992.

[iii] Vickers Ruwolt Proprietary Limited, Melbourne, Australia, nd, np.

[iv] Alfred Heintz, The Fabulous Hill, BHP, 1960, np.

[v] Daniel Palmer, ‘Wolfgang Sievers’, Flash, Centre for Contemporary Photography Newsletter, June-Spetmeber 2004, pp10-11.

[vi] Photographers of Australia

[vii] Helen Ennis, ‘Wolfgang Sievers’, Photographers of Australia: Dupain, Sievers, Moore, Film Australia, 1992, np.

[viii] Anne Brennan, ‘A Philosophical Approach to Design: Gerhard Herbst and Fritz Janeba’, in The Europeans : emigré artists in Australia, 1930-1960, (ed) Roger Butler, National Gallery of Australia, 1997.

[ix] Helen Ennis, ‘Blue Hydrangeas: Four Emigré Photographers’, in The Europeans : emigré artists in Australia, 1930-1960, p105.

[x] Conrad Hamann, ‘Frederick Romberg and the Problem of European Authenticity’, in The Europeans : emigré artists in Australia, 1930-1960.

[xi] Harriet Edquist, Ernest Fooks: Architect, RMIT, 2001, p20.

[xii] Linda Groom, ‘the Dignity of Man as a Worker; The Sievers Archive’, National Library of Australia News, January 2003, np.