Thank you Gerrit Fokkema and Lisa Moore for giving me the privilege of attempting to sum up Wes Stacey’s contribution to Australian photography for the diverse audience who came to his Memorial at Powerhouse on 30 March. And thank you to the other organisers and participants of the event. This is what I said:

Wes Stacey

Before I begin, I would like to acknowledge the Gadigal of the Eora Nation as traditional custodians of the land upon which we meet.

I’m a photo historian, and my role in this evening’s memorial is to reflect on Wes’s contribution to Australian photography. For this, I’m drawing upon the work of other people who have long recognised Wes’s historical importance. They are Gael Newton, Stephen Zagala, Ziv Cohen and Belinda Hungerford.

Wes’s career was protean, and it is easy to see it as separate bits that at first glance contradict each other. But I think some abiding concerns underly it all.

One of those underlying concerns was a strong sense of history. In the early 60s, when he was working in their graphics department, the ABC did a story on the Holtermann Collection of colonial negatives that had been famously discovered at a suburban house, and Wes found that encounter very stimulating.

Afterwards, he went to London and began to really make a go of it as a photographer, but he decided to return to Australia after just two years. He was, he told his British friends, “returning to his Australian roots”.

A few years after his return he began to produce a remarkable series of coffee table books on colonial architecture with Phillip Cox. His black and white photographs for these books are tight and architectural, solidly constructed within framing trees out of rectilinear compositional elements set at right angles to each other. For Wes these compositions came from Russell Drysdale, Max Dupain and David Moore, while his interest in colonial architecture itself came from memories of his own childhood houses, and a burgeoning interest in Australian places.

So, place is another underlying idea.

At the same time as Wes was producing these big heavy books on colonial places with Philip Cox, he was also working for the tyro/gonzo publisher Gareth Powell on the men’s magazine Chance and the women’s magazine POL. The magazine work springs from Wes’s hippy hedonism: the dope, the wine, the women. The hyped-up, psychedelic, nude, fashion, and editorial spreads are shot at wide angle, in colour, and on transparency film. In the context of other Australian photography at the time they are truly experimental. That’s why I think that Wes’s failures, such as the bilious cross processing used in the ski fashion shoot for an issue of POL, are so interesting, and should be celebrated,

So that is another abiding interest — transformation.

Experimenting on the front covers of national magazines was something that Wes just did, because he was Wes. As Robert McFarlane wrote in 1968:

‘Physically, Wes Stacey could almost be the epitome of the intense, passionately committed photographer today. Stacey is lean and tall, with a face crowned with a head of the most preposterously curly hair’.

Wes’s sheer presence was the reason he was an integral part of the founding of the Australian Centre for Photography. There is a photograph taken around 1971 by David Moore of Harry Williamson, Peter Keys and Wes at a planning meeting for the ACP. They are all holding beers and looking at a large sheet of butcher’s paper which is headed: “The first extraordinary meeting of the continuous exhibition and archive of photographic art”. But somebody has crossed out and the letter “c” and the word “art”, so it’s not “photographic art” but just “photography”. So much better. Such a crucial point to make. Which one of them did it, I wonder? I bet I know who it was.

This period produced other books, which aren’t as big and posh as the colonial books but are just as important. For Kings Cross Sydney, his medium format Hasselblad colour, sometimes using the same wide-angle lenses he used for his magazine work, integrate well with Rennie Ellis’s cheeky and sly 35mm Pentax shots. This is by far the best book about The Cross of the period, because it treated it as crucial place within Australia as a whole.

Australia as a whole was an abiding concern for Wes. Travel was his way to find it. He had bought a motor scooter at the age of 16, and his first car at 18, then there was the famous Kombi. With the crucial, collaborative support of his partners Barbara Wilson, Eleanor Williams, and Narelle Perroux he drove back and forth, back and forth across Australia. But, in an era when leaving the city to find something by going ‘Outback’ was a ‘thing’, that is precisely what Wes didn’t do. Rather, like a large-scale performance artist, he traversed Australia equally, almost formally, edge to edge from its cities to its suburbs, its seas to its deserts.

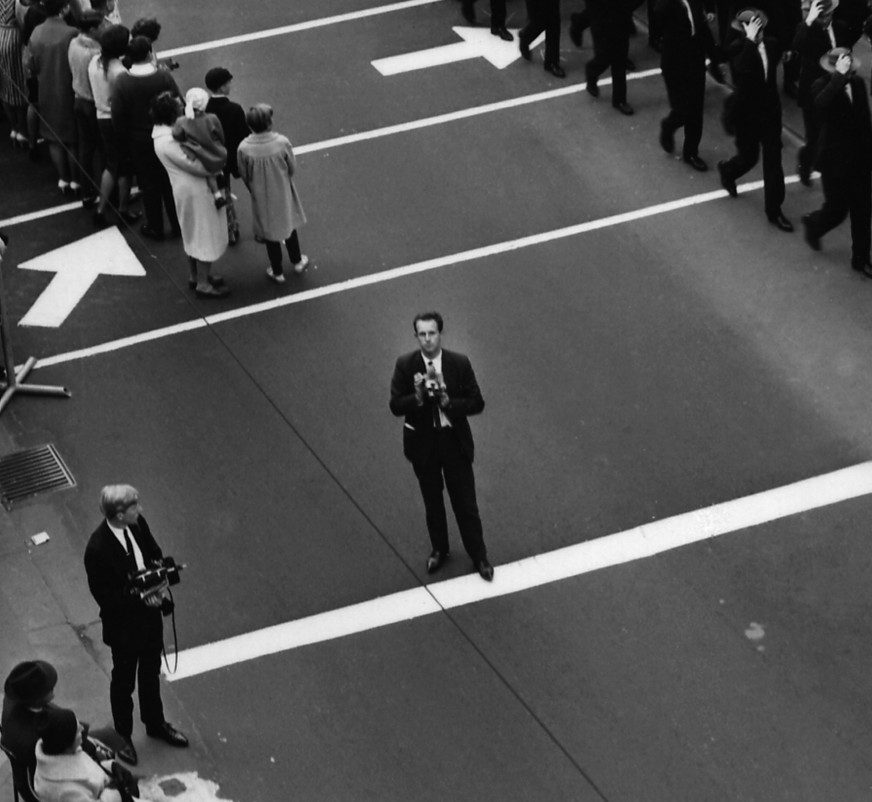

In the early 70s, Wes began to use a 110 Instamatic Camera, and that one-handed Kodak camera synchronised with the one-handed Kombi steering wheel for his most famous exhibition and series of artist books, The Road of 1975, where rhythmic sequences of spontaneous images plucked from behind grimy windscreens or windows half rolled down in the heat were coolly laid out in long, formal strips. By that stage, the ACP which Wes had helped found had opened, and to celebrate they had brought out the power-broking curator from New York’s Museum of Modern Art, John Szarkowski, for a kind of ‘Papal tour’. And who did he anoint? He said that Wes’s exhibitions were ‘the most radical thing he had seen’ in Australia.

A few years earlier, when Wes was shooting in Silverton for the architectural book Historic Towns of Australia, he photographed an Aboriginal man outside a ruined building. To be honest, the photographs aren’t all that great, they could easily have been taken by any other Australian photographer of the time. But, as Gael Newton and Paul Costigan were uploading them to their web site, Wes told them about the experience of photographing that Aboriginal man. He said that he “was nervous, didn’t know if this would be a confrontation … he was friendly, let me take photographs … but [I] didn’t understand what he was saying”. But within just a few years of this typical ‘Aussie’ encounter between white and black, another encounter with another Aboriginal man was to have a profound impact on him.

Wes moved to a bush camp on the far south coast of New South Wales around the mid 1970s. I began these remarks with the standard Acknowledgement of Country everybody does, but Wes really, deeply, truly acknowledged the custodians of the country where he had decided to live. He became a photographic activist within the environmental campaigns to stop the logging of the old growth forests of the area. He collaborated with Guboo Ted Thomas, an elder from the Wallaga Lake community who was charismatic, and something of a self-styled spiritual guru. This led to another extremely important book, Mumbulla-Spiritual-Contact of 1980. Unlike the big, heavy coffee table books, or the mass-produced Kings Cross Sydney, this one was large format, carefully printed, and spiral bound. One startling spread shows Wes’s sense of history, it juxtaposes a shot of monumental anthropomorphic rocks amid dense trees, with a crumpled, creased, and torn snapshot of Aboriginal men on a mission station.

This enduring involvement with a community and its struggle also led to an important exhibition. Wes had always been interested in different ways of exhibiting photographs for their impact, and as part of the political campaign to save Mumbulla Mountain, which was sacred to the Yuin People, from logging, he mounted metre-square prints on hessian screens and displayed them as The Law Comes From The Mountain, at Town Hall Plaza, Sydney, and Capital Hill and Parliament House, Canberra, right where the environmental laws were being made.

Later, in 1982, Wes and Narelle Perroux and Marcia Langton produced a travelling exhibition and book, After the Tent Embassy: Images of Aboriginal History in Black and White Photographs. I think it is impossible to overstate the importance of this project for Australia. It invented in one go a whole new visual grammar for Indigenous debates by juxtaposing horrible, inert, colonial photographs with a variety of marvellous new photographs of Aboriginal life and activism. This brilliant juxtaposition animated the historical photographs with new power and freighted the contemporary photographs with urgent weight.

Wes’s sense of history and place and transformation and travel were all underpinned by his spirituality. As a young man he had prayed every night to a Christian god, later he became interested in Buddhism, Sufism, and Aboriginal spiritualities. As evidenced in the book he made with Eleanor Williams, Timeless Gardens, his spirituality found most direct expression in his landscape photography.

Over the arc of his career, there is a profound philosophical change in the shift from the square format Hasselblad to the panoramic Widelux; from a Eurocentric, rectangular, window-like framing to a sweeping embrace, where the camera lens gathers up the landscape into its arms. But the change is also evident in his printing. He spent the late 1970s down amongst the coastal topography with Guboo Ted Thomas ‘learning to photograph the bush’ — a very humble statement for somebody who had already been successfully photographing it for fifteen years. This also meant, in part, opening up the shadows in his prints. It’s a shock to our sensibilities to see just how heavily Wes printed black and white back in the 1960s. On the pages of those big posh coffee table books all the shadows are thick pools of ink where Australia shrinks from the hard light. But later, in the prints made after his move to the south coast, we sink into its folds and its fronds and join our ‘Koori mates’.

In the portrait Wes has titled “Guboo Aboriginal Elder Defending Mumbulla Mountain from loggers 1979″, Guboo makes a heroic frieze as the patterns of his cable knit jumper, folded raincoat and creased trousers integrate with the foliage in which he is embedded, while drops of dew, in a classic Wes moment, cling to the stems of grass in the foreground, waiting to evaporate with time. Nowadays, paying such respects to ‘elders past, present and emerging’ is commonplace, but it wasn’t so commonplace in 1979.

Although Australia was the root of Wes’s spirituality, it didn’t confine it. He shot sacred places in Britain, Europe and Japan, and the exhibition he was most proud of was Landscape for Peace in 1994, where his framed panoramas were displayed on easels inside the ancient Kiyomizu Temple in Kyoto.

Although these reflections draw on the work of my photo-historical colleagues, I’d like to end with a personal anecdote. In 1975 a sixteen-year-old boy was sitting on the vinyl couch of his parent’s house in Brisbane. He was watching one of his favourite TV shows on channel two, the youth program GTK. Occasionally this show opened up glimpses of other worlds to him. Suddenly, an old Kombi pulls up on the screen and a hairy hippy jumps out. This didn’t impress the Brisbane boy too much, he already knew about Kombis and hippies. The hairy hippy, who was probably promoting his ACP show The Road through the contacts he had from when he used to work at the ABC, pulled out an instamatic camera and approached the wing mirror of his Kombi. This didn’t impress the Brisbane boy much either, he also had an instamatic camera and had already seen some photographs of car mirrors in the photography books he was beginning to devour. But then the hairy hippy went round to the back of the wing mirror and photographed the distorted reflection in the chrome. And this did impress the Brisbane boy. You could do that?!?

So, when it comes to Wes’s enormous contribution to Australian photography, he didn’t make it the way most of us ‘make a contribution’, he didn’t just get up every morning and ‘clock on to work’ to make his contribution. Instead, he made his contribution by simply and completely being Wes Stacey. He embodied his photography, he lived it. And he was an enthusiastic and generous and loving man, so his living of photography became our living of photography. That was his contribution.

Thank you.