From the Empire’s End, 1993

Judith Ahem. Bill Henson, Rozalind Drummond.

Adrian Hall. Linda Dement. Helen Grace.

Tracey Moffatt. Sue Ford, and Peter Elliston

Madrid, 7 March-14 April, 1991 NSW Regional Eaileries tour and IVan Dougherty Gallery. Sydney 30 Sept-23 Oct 1993

Photofile 39 July 1993

Lately the idea of international cultural exchange has become fundamental to Australian art. The tail end of one such exchange is currently touring Australia. In early 1991 an exhibition of ten Spanish photographers came to Australia and an Australian exhibition went to Spain. However, rather than being driven by the ‘soft diplomacy’ policy of the Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade (DFAT), as is our current arts push into Asia, this exchange came about entirely through the personal enthusiasms of individuals in Australia and Spain. It therefore had a pleasingly quixotic air to it.

The Spanish show, On the Shadow Line arrived in Australia with its curator Alejandro Castellote in early 1991. The curatorial rationale of his show was to demonstrate that Spanish photography was still in a convulsive state as Spain slowly pulled itself out of the shadowy past of Franco towards the future of Modern Europe.

However, the Australian audience appeared unable to translate this moment of cultural transformation into the photography itself. To many of them the extreme diversity of work in On the Shadow Line read merely as unsatisfactory eclecticism. Fot instance what many, quite rightly, wanted to know was: if this was meant to be a survey of the current developing state of Spanish photography then where were the women photographers?

Terence Maloon’s selection of Australian photographers From the Empire’s End was just as eclectic. But it did not claim to represent any totalised idea of Australian photography. Those curatorially proper things which group shows such as this are normally meant to be about -an assessment of the state of photography as a discipline, a prediction of the next big thing, a debut of new talent, a sniffing of the air in the current Zeitgeist – all appear to be the very last things on Maloon’s mind. The artists Maloon selected for the exhibition may just have been the artists Maloon liked at the time. Or the wilful and extreme contrasts between them – in style, tone, mood, ideology, content, medium, genre, and generation – could be an attempt to present them not just as a pool of talent, but as a deliberate battlefield.

He refused to present Australia as an exotic Other to Europe, he refused to claim that Australian photographers could collectively represent the state of being either the colonised or coloniser, and he refused the consolation of landscape as the great redeemer of all our bewildering differences. These refusals added up to the reigning metaphor for the exhibition: deterritorialisation. Every photographer in the show, Maloon claimed in the introduction, upsets some accepted notion of the proper place of things: the place of the viewer and the viewed on either side of the image, the place of the body outside language, the place of gender or race to one side of power, the place of the mutually exclusive immigrant and indigenous peoples within the Empire, and the place of landscape as the ground of nationhood.

This clearly bemused the Spanish reviewers of the show. Few did more than summarise the show’s catalogue and describe some of the works, and none dared to make any more than the most parochial of assessments of its quality (which was exactly the Australian critical reaction to the Spanish show).

But now, two years later and after bumping round Spain, the show is back in Australia and set for a tour lasting until well into next year. Perhaps, ironically, Australia will provide its own best audience for the work. After three years has worn the dazzle of currency off the works, and after the diplomatic protocols of national ‘presentation’ implicit in any cultural exchange have faded into history, perhaps the audacity of Maloon’s selection can be assessed.

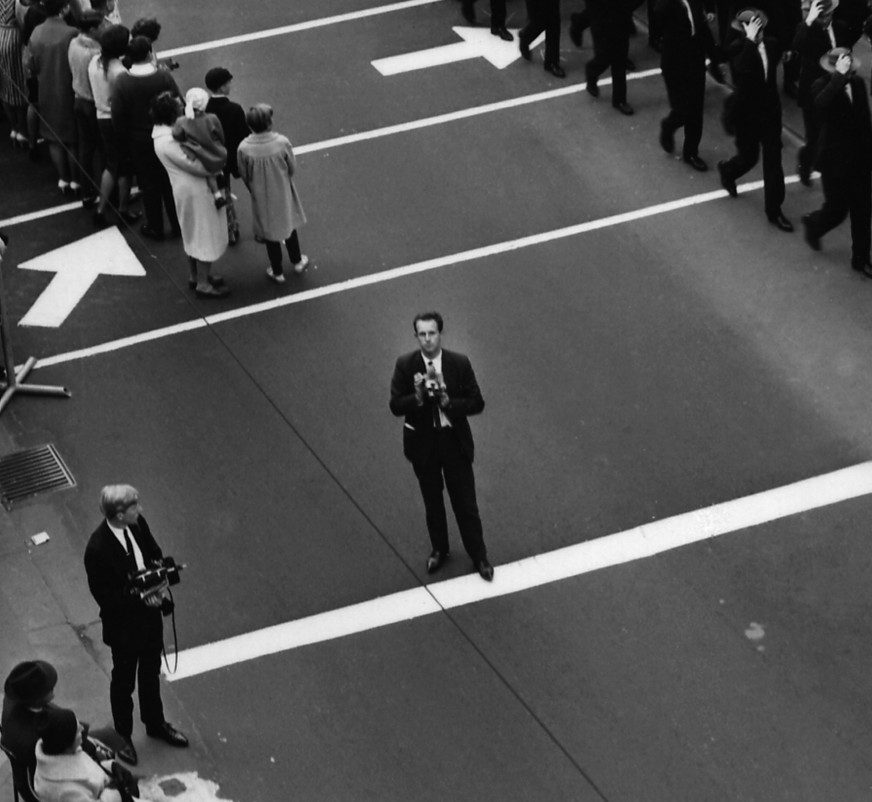

The photographers in the exhibition are certainly undiplomatic. Helen Grace’s frenetic, xerox-coloured stockbrokers yell at the melancholic citizens of Bill Henson’s own private entropic nation. Judith Ahern’s found images of hapless Kodak customers, permanently trapped in the surreal world created when their snapshots were arbitrarily sandwiched together by a fault in Kodak’s processing machine, look out at Adrian Hall’s careful and deliberate self presentation in his cibachrome theatres of symbol, expressionis-tic gesture and performance. Tracey Moffatt’s composite characters – rich compendiums of stereotypes displaced onto a narrative of the self- act out in front of Linda Dement’s clinical self-dissection of her body as cultural text. The pristine irony of warships looming on the horizon behind the beach in Peter Elliston’s landscapes contrasts with the cinematic, vertiginous point of view of Rozalind Drum-mond’s cities. Whilst all the time Sue Ford’s apparently ‘ordinary’ documentary shots of a supposed reconciliation between white and black just refuse to settle down in their frames.

The exhibition, Maloon says in the catalogue, was ‘about differences, but it was conceived to avoid the kind of presentation that European audiences could construe as Difference pure and simple’. Now it is the turn of Australian audiences to construe these differences. Australians are used to imagining themselves as others see them. Perhaps the benefits of this cultural exchange will be all one sided, having returned to Australia from beneath Europe’s bemused gaze the arguments between Australia’s differences may finally become a debate.

Marryn Jolly